Home > Press > Making quantum puddles: Physicists discover how to create the thinnest liquid films ever

|

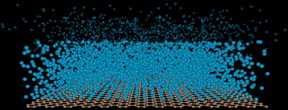

| In a vacuum, a suspended sheet of one-atom-thick graphene (brown lattice) could be manipulated to create a liquid film (atoms in dark blue) that stops growing at a thickness between 3 and 50 nanometers. By stretching the graphene, doping it with other atoms, or applying a weak electrical field nearby, the University of Vermont researchers who made the discovery have evidence that the number of atoms in an ultra-thin film can be controlled. CREDIT courtesy Adrian Del Maestro et al. |

Abstract:

A team of physicists at the University of Vermont have discovered a fundamentally new way surfaces can get wet. Their study may allow scientists to create the thinnest films of liquid ever made--and engineer a new class of surface coatings and lubricants just a few atoms thick.

Making quantum puddles: Physicists discover how to create the thinnest liquid films ever

Burlington, VT | Posted on June 13th, 2018"We've learned what controls the thickness of ultra-thin films grown on graphene," says Sanghita Sengupta, a doctoral student at UVM and the lead author on the new study. "And we have a good sense now of what conditions--like knobs you can turn--will change how many layers of atoms will form in different liquids."

The results were published June 8 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

A THIRD WAY

To understand the new physics, imagine what happens when rain falls on your new iPhone: it forms beads on the screen. They're easy to shake off. Now imagine your bathroom after a long shower: the whole mirror may be covered with a thin layer of water. "These are two extreme examples of the physics of wetting," says UVM physicist Adrian Del Maestro, a co-author on the new study. "If interactions inside the liquid are stronger than those between the liquid and surface, the liquid atoms stick together, forming separate droplets. In the opposite case, the strong pull of the surface causes the liquid to spread, forming a thin film."

More than 50 years ago, physicists speculated about a third possibility--a strange phenomena called "critical wetting" where atoms of liquid would start to form a film on a surface, but then would stop building up when they were just a few atoms thick. These scientists in the 1950s, including the famed Soviet physicist Evgeny Lifshitz, weren't sure if critical wetting was real, and they certainly didn't think it would ever be able to be seen in the laboratory.

Then, in 2010, the Nobel Prize in physics was awarded to two Russian scientists for their creation of a bizarre form of carbon called graphene. It's a honeycombed sheet of carbon just one atom thick. It's the strongest material in the world and has many quirky qualities that materials scientists have been exploring ever since.

Graphene turns out to be the "ideal surface to test for critical wetting," says Del Maestro--and with it the Vermont team has now demonstrated mathematically that critical wetting is real.

HARNESSING VAN DER WAALS FORCE

The scientists explored how three light gases--hydrogen, helium and nitrogen--would behave near graphene. In a vacuum and other conditions, they calculated that a liquid layer of these gases will start to form on the one-atom-thick sheet of graphene. But then the film stops growing when "it is ten or twenty atoms thick," says Valeri Kotov, an expert on graphene in UVM's Department of Physics and the senior author on the study.

The explanation can be found in quantum mechanics. Though a neutral atom or molecule--like the light gases studied by the UVM team--has no overall electric charge, the electrons constantly circling the far-off nucleus (OK, "far-off" only from the scale of an electron) form momentary imbalances on one side of the atom or another. These shifts in electron density give rise to one of the pervasive but weak powers in the universe: Van der Waals force. The attraction it creates between atoms only extends a short distance.

Because of the outlandish, perfectly flat geometry of the graphene, there is no electrostatic charge or chemical bond to hold the liquid, leaving the puny van der Waals force to do all the heavy lifting. Which is why the liquid attached to the graphene stops attracting additional atoms out of the vapor when the film has grown to be only a few atoms away from the surface. In comparison, even the thinnest layer of water on your bathroom mirror--which is formed by many much more powerful forces than just the quantum-scale effects of van der Waals force--would be "in the neighborhood of 109 atoms thick," says Del Maestro; that's 1,000,000,000 atoms thick.

APPLIED WETNESS

Engineering a surface where this kind of weak force can be observed has proven very challenging. But the explosion of scientific interest in graphene has allowed the UVM scientists to conclude that critical wetting seems to be a universal phenomenon in the numerous forms of graphene now being created and across the growing family of other two-dimensional materials.

The scientists' models show that, in a vacuum, a suspended sheet of graphene (above) could be manipulated to create a liquid film (atoms in blue, above) that stops growing at a thickness of a much as 50 nanometers, down to a thickness of just three nanometers. "What's important is that we can tune this thickness," says Sengupta. By stretching the graphene, doping it with other atoms, or applying a weak electrical field nearby, the researchers have evidence that the number of atoms in an ultra-thin film can be controlled.

The mechanical adjustment of the graphene could allow real-time changes in the thickness of the liquid film. It might be a bit like turning a "quantum-sized knob," says Nathan Nichols--another UVM doctoral student who worked on the new study--on the outside of an atomic-scale machine in order to change the surface coating on moving parts inside.

Now this team of theoretical physicists--"I'm starting to call what I do dielectric engineering," says Sengupta--is looking for a team of experimental physicists to test their discovery in the lab.

Much of the initial promise of graphene as an industrial product has not yet been realized. Part of the reason why is that many of its special properties--like being a remarkably efficient conductor--go away when thick layers of other materials are stuck to it. But with the control of critical wetting, engineers might be able to customize nanoscale coatings which wouldn't blot out the desired properties of graphene, but could, says Adrian Del Maestro, offer lubrication and protection of "next-generation wearable electronics and displays."

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Joshua Brown

802-656-3039

Copyright © University of Vermont

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

| Related News Press |

Quantum Physics

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

2 Dimensional Materials

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

![]() Closing the gaps — MXene-coating filters can enhance performance and reusability February 28th, 2025

Closing the gaps — MXene-coating filters can enhance performance and reusability February 28th, 2025

Display technology/LEDs/SS Lighting/OLEDs

![]() Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

Graphene/ Graphite

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Wearable electronics

![]() Breakthrough brings body-heat powered wearable devices closer to reality December 13th, 2024

Breakthrough brings body-heat powered wearable devices closer to reality December 13th, 2024

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Chip Technology

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Materials/Metamaterials/Magnetoresistance

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

![]() Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

![]() Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Water

![]() Taking salt out of the water equation October 7th, 2022

Taking salt out of the water equation October 7th, 2022

Quantum nanoscience

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||