Home > Press > Engineers teach old chemical new tricks to make cleaner fuels, fertilizers: Researchers from Denmark and Stanford show how to produce industrial quantities of hydrogen without emitting carbon into the atmosphere

|

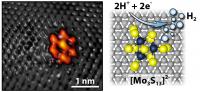

| On the left, a scanning tunneling microscope image captures the bright shape of the moly sulfide nanocluster on a graphite surface. The grey spots are carbon atoms. Together the moly sulfide and graphite make the electrode. The diagram on the right shows how two positive hydrogen ions gain electrons through a chemical reaction at the moly sulfide nanocluster to form pure molecular hydrogen.

Credit: Jakob Kibsgaard |

Abstract:

University researchers from two continents have engineered an efficient and environmentally friendly catalyst for the production of molecular hydrogen (H2), a compound used extensively in modern industry to manufacture fertilizer and refine crude oil into gasoline.

Engineers teach old chemical new tricks to make cleaner fuels, fertilizers: Researchers from Denmark and Stanford show how to produce industrial quantities of hydrogen without emitting carbon into the atmosphere

Stanford, CA | Posted on January 27th, 2014Although hydrogen is abundant element, it is generally not found as the pure gas H2but is generally bound to oxygen in water (H2O) or to carbon in methane (CH4), the primary component in natural gas. At present, industrial hydrogen is produced from natural gas using a process that consumes a great deal of energy while also releasing carbon into the atmosphere, thus contributing to global carbon emissions.

In an article published today (Jan. 26, 1300 EST) in Nature Chemistry, nanotechnology experts from Stanford Engineering and from Denmark's Aarhus University explain how to liberate hydrogen from water on an industrial scale by using electrolysis .

In electrolysis, electrical current flows through a metallic electrode immersed in water. This electron flow induces a chemical reaction that breaks the bonds between hydrogen and oxygen atoms. The electrode serves as a catalyst, a material that can spur one reaction after another without ever being used up. Platinum is the best catalyst for electrolysis. If cost were no object, platinum might be used to produce hydrogen from water today.

But money matters. The world consumes about 55 billion kilograms of hydrogen per year. It now costs about $1 to $2 per kilogram to produce hydrogen from methane. So any competing process, even if it's greener, must hit that production cost, which rules out electrolysis based on platinum.

In their Nature Chemistry paper, the researchers describe how they re-engineered the atomic structure of a cheap and common industrial material to make it nearly as efficient at electrolysis as platinum - a finding that has the potential to revolutionize industrial hydrogen production.

The project was conceived by Jakob Kibsgaard, a post-doctoral researcher with Thomas Jaramillo, an assistant professor of chemical engineering at Stanford. Kibsgaard started this project while working with Flemming Besenbacher, a professor at the Interdisciplinary Nanoscience Center (iNANO) at Aarhus.

Subhead: Meet Moly Sulfide

Since World War II petroleum engineers have used molybdenum sulfide - moly sulfide for short - to help refine oil.

Until now, however, this chemical was not considered a good catalyst for making moly sulfide to produce hydrogen from water through electrolysis. Eventually scientists and engineers came to understand why: the most commonly used moly sulfide materials had an unsuitable arrangement of atoms at their surface.

Typically, each sulfur atom on the surface of a moly sulfide crystal is bound to three molybdenum atoms underneath. For complex reasons involving the atomic bonding properties of hydrogen, that configuration isn't conducive to electrolysis.

In 2004, Stanford chemical engineering professor Jens Norskov, then at the Technical University of Denmark, made an important discovery. Around the edges of the crystal, some sulfur atoms are bound to just two molybdenum atoms. At these edge sites, which are characterized by double rather than triple bonds, moly sulfide was much more effective at forming H2.

Armed with that knowledge, Kibsgaard found a 30-year-old recipe for making a form of moly sulfide with lots of these double-bonded sulfurs at the edge.

Using simple chemistry, he synthesized nanoclusters of this special moly sulfide. He deposited these nanoclusters onto a sheet of graphite, a material that conducts electricity. Together the graphite and moly sulfide formed a cheap electrode. It was meant to be a substitute for platinum, the ideal but expensive catalyst for electrolysis.

The question then became: could this composite electrode efficiently spur the chemical reaction that rearranges hydrogen and oxygen atoms in water?

As Jaramillo put it: "Chemistry is all about where electrons want to go, and catalysis is about getting those electrons to move to make and break chemical bonds."

Subhead: The acid test

So the experimenters put their system to the acid test -- literally.

They immersed their composite electrode into water that was slightly acidified, meaning it contained positively charged hydrogen ions. These positive ions were attracted to the moly sulfide clusters. Their double-bonded shape gave them just the right atomic characteristic to pass electrons from the graphite conductor up to the positive ions. This electron transfer turned the positive ions into neutral molecular hydrogen, which bubbled up and away as a gas.

Most importantly, the experimenters found that their cheap, moly sulfide catalyst had the potential to liberate hydrogen from water on something approaching the efficiency of a system based on prohibitively expensive platinum.

Subhead: Yes, but does it scale?

But in chemical engineering, success in a beaker is only the beginning.

The larger questions were: could this technology scale to the 55 billion kilograms per year global demand for hydrogen, and at what finished cost per kilogram?

Last year, Jaramillo and a dozen co-authors studied four factory-scale production schemes in an article for The Royal Society of Chemistry's journal of Energy and Environmental Science.

They concluded that it could be feasible to produce hydrogen in factory-scale electrolysis facilities at costs ranging from $1.60 and $10.40 per kilogram - competitive at the low end with current practices based on methane -- though some of their assumptions were based on new plant designs and materials.

"There are many pieces of the puzzle still needed to make this work, and much effort ahead to realize them," Jaramillo said. "However, we can get huge returns by moving from carbon-intensive resources to renewable, sustainable technologies to produce the chemicals we need for food and energy."

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Tom Abate

650-736-2245

Copyright © Stanford School of Engineering

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

Chemistry

![]() Projecting light to dispense liquids: A new route to ultra-precise microdroplets January 30th, 2026

Projecting light to dispense liquids: A new route to ultra-precise microdroplets January 30th, 2026

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Food/Agriculture/Supplements

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() SMART researchers pioneer first-of-its-kind nanosensor for real-time iron detection in plants February 28th, 2025

SMART researchers pioneer first-of-its-kind nanosensor for real-time iron detection in plants February 28th, 2025

![]() Silver nanoparticles: guaranteeing antimicrobial safe-tea November 17th, 2023

Silver nanoparticles: guaranteeing antimicrobial safe-tea November 17th, 2023

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Industrial

![]() Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

![]() Quantum interference in molecule-surface collisions February 28th, 2025

Quantum interference in molecule-surface collisions February 28th, 2025

![]() Boron nitride nanotube fibers get real: Rice lab creates first heat-tolerant, stable fibers from wet-spinning process June 24th, 2022

Boron nitride nanotube fibers get real: Rice lab creates first heat-tolerant, stable fibers from wet-spinning process June 24th, 2022

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||