Home > Press > Scientists Reveal Effects of Quantum “Traffic Jam” in High-Temperature Superconductors

|

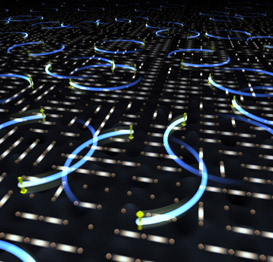

| This image shows two states of a cuprate high-temperature superconductor simultaneously: Each circle represents the two electrons of a Cooper pair, which exist at relatively low energy and can carry current with no resistance. In this image, the superconducting Cooper-pair state is superimposed on a dashed pattern that indicates the static positions of electrons caught in a quantum "traffic jam" at higher energy - when the material acts as a Mott-insulator incapable of carrying current. |

Abstract:

Findings may point to new materials to get the current flowing at higher temperatures

Scientists Reveal Effects of Quantum “Traffic Jam” in High-Temperature Superconductors

UPTON, NY | Posted on August 28th, 2008Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory, in collaboration with colleagues at Cornell University, Tokyo University, the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Colorado, have uncovered the first experimental evidence for why the transition temperature of high-temperature superconductors — the temperature at which these materials carry electrical current with no resistance — cannot simply be elevated by increasing the electrons' binding energy. The research — to be published in the August 28, 2008, issue of Nature — demonstrates how, as electron-pair binding energy increases, the electrons' tendency to get caught in a quantum mechanical "traffic jam" overwhelms the interactions needed for the material to act as a superconductor — a freely flowing fluid of electron pairs.

"We've made movies to show this traffic jam as a function of energy. At some energies, the traffic is moving and at others the electron traffic is completely blocked," said physicist J.C. Seamus Davis of Brookhaven National Laboratory and Cornell University, lead author on the paper. Davis will be giving a Pagels Memorial Public Lecture to announce these results at the Aspen Center for Physics on August 27.

Understanding the detailed mechanism for how quantum traffic jams (technically referred to as "Mottness" after the late Sir Neville Mott of Cambridge, UK) impact superconductivity in cuprates may point scientists toward new materials that can be made to act as superconductors at significantly higher temperatures suitable for real-world applications such as zero-loss energy generation and transmission systems and more powerful computers.

The idea that increasing binding energy could elevate a superconductor's transition temperature stems from the mechanism underlying conventional superconductors' ability to carry current with no resistance. In those materials, which operate close to absolute zero (0 kelvin, or -273 degrees Celsius), electrons carry current by forming so-called Cooper pairs. The more strongly bound those electron pairs, the higher the transition temperature of the superconductor.

But unlike those metallic superconductors, the newer forms of high-temperature superconductors, first discovered some 20 years ago, originate from non-metallic, Mott-insulating materials. Elevating these materials' pair-binding energy only appears to push the transition temperature farther down, closer to absolute zero rather than toward the desired goal of room temperature or above.

"It has been a frustrating and embarrassing problem to explain why this is the case," Davis said. Davis's research now offers an explanation.

In the insulating "parent" materials from which high-temperature superconductors arise, which are typically made of materials containing copper and oxygen, each copper atom has one "free" electron. These electrons, however, are stuck in a Mott insulating state — the quantum traffic jam — and cannot move around. By removing a few of the electrons — a process called "hole doping" — the remaining electrons can start to flow from one copper atom to the next. In essence, this turns the material from an insulator to a metallic state, but one with the startling property that it superconducts — it carries electrical current effortlessly without any losses of energy.

"It's like taking some cars off the highway during rush hour. All of a sudden, the traffic starts to move," said Davis.

The proposed mechanism for how these materials carry the current depends on magnetic interactions between the electrons causing them to form superconducting Cooper pairs. Davis's research, which used "quasiparticle interference imaging" with a scanning tunneling microscope to study the electronic structure of a cuprate superconductor, indicates that those magnetic interactions get stronger as you remove holes from the system. So, even as the binding energy, or ability of electrons to link up in pairs, gets higher, the "Mottness," or quantum traffic-jam effect, increases even more rapidly and diminishes the ability of the supercurrent to flow.

"In essence, the research shows that what is believed to be required to increase the superconductivity in these systems — stronger magnetic interactions — also pushes the system closer to the 'quantum traffic-jam' status, where lack of holes locks the electrons into positions from which they cannot move. It's like gassing up the cars and then jamming them all onto the highway at once. There's lots of energy, but no ability to go anywhere," Davis said.

With this evidence pointing the scientists to a more precise theoretical understanding of the problem, they can now begin to explore solutions. "We need to look for materials with such strong pairing but which don't exhibit this Mottness or 'quantum traffic-jam' effect," Davis said.

Scientists at Brookhaven are now investigating promising new materials in which the basic elements are iron and arsenic instead of copper and oxygen. "Our hope is that they will have less 'traffic-jam' effect while having stronger electron pairing," Davis said. Techniques developed for the current study should allow them to find out.

This research was funded primarily by the Brookhaven Lab's Laboratory-Directed Research and Development Fund, by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences within DOE's Office of Science, by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Science and Education (Japan), and by the 21st Century COE Program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

####

About Brookhaven National Laboratory

One of ten national laboratories overseen and primarily funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Brookhaven National Laboratory conducts research in the physical, biomedical, and environmental sciences, as well as in energy technologies and national security. Brookhaven Lab also builds and operates major scientific facilities available to university, industry and government researchers. Brookhaven is operated and managed for DOE’s Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates, a limited-liability company founded by Stony Brook University, the largest academic user of Laboratory facilities, and Battelle, a nonprofit, applied science and technology organization.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Karen McNulty Walsh

(631) 344-8350

or

Mona S. Rowe

(631) 344-5056

Copyright © Brookhaven National Laboratory

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

Videos/Movies

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Quantum nanoscience

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||