Home > Press > A new way to mix oil and water: Condensation-based method developed at MIT could create stable nanoscale emulsions

|

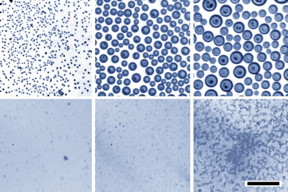

| Optical images demonstrate that when water droplets condense on an oil bath, the droplets rapidly coalesce to become larger and larger (top row of images, at 10-minute intervals). Under identical conditions but with a soap-like surfactant added (bottom row), the tiny droplets are much more stable and remain small. Courtesy of the researchers |

Abstract:

The reluctance of oil and water to mix together and stay that way is so well-known that it has become a cliché for describing any two things that do not go together well. Now, a new finding from researchers at MIT might turn that expression on its head, providing a way to get the two substances to mix and remain stable for long periods — no shaking required. The process may find applications in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and processed foods, among other areas.

A new way to mix oil and water: Condensation-based method developed at MIT could create stable nanoscale emulsions

Cambridge, MA | Posted on November 8th, 2017The new process involves cooling a bath of oil containing a small amount of a surfactant (a soap-like substance), and then letting water vapor from the surrounding air condense onto the oil surface. Experiments have shown that this can produce tiny, uniform water droplets on the surface that then sink into the oil, and their size can be controlled by adjusting the proportion of surfactant. The findings, by MIT graduate student Ingrid Guha, former postdoc Sushant Anand, and associate professor Kripa Varanasi, are reported in the journal Nature Communications.

As anyone who has ever used salad dressing knows, no matter how vigorously the mixture gets shaken, the oil and the vinegar (a water-based solution) will separate within minutes. But for many uses, including new drug-delivery systems and food-processing methods, it’s important to be able to get oil in water (or water in oil) to form tiny droplets — only a few hundred nanometers across, too small to see with the naked eye — and to have them stay tiny rather than coalescing into larger droplets and eventually separating from the other liquid.

Typically, in industrial processes these emulsions are made by either mechanically shaking the mix or using sound waves to set up intense vibrations within the liquid, a process called sonicating. But both of these processes “require a lot of energy,” Varanasi says, “and the finer the drops, the more energy it takes.” By contrast, “our approach is very energy inexpensive,” he adds.

“The key to overcoming that separation is to have really small, nanoscale droplets,” Guha explains. “When the drops are small, gravity can’t overcome them,” and they can remain suspended indefinitely.

For the new process, the team set up a reservoir of oil with an added surfactant that can bind to both oil and water molecules. They placed this inside a chamber with very humid air and then cooled the oil. Like a glass of cold water on a hot summer day, the colder surface causes the water vapor to precipitate. The condensing water then forms droplets at the surface that spread through the oil-surfactant mixture, and the sizes of these droplets are quite uniform, the team found. “If you get the chemistry just right, you can get just the right dispersion,” Guha says. By adjusting the proportion of surfactant in the oil, the droplet sizes can be well-controlled.

In the experiments, the team produced nanoscale emulsions that remained stable over periods of several months, compared to the few minutes that it takes for the same mixture of oil and water to separate without the added surfactant. “The droplets stay so small that they’re hard to see even under a microscope,” Guha says.

Unlike the shaking or sonicating methods, which take the large, separate masses of oil and water and gradually get them to break down into smaller drops — a “top down” approach — the condensation method starts off right away with the tiny droplets condensing out from the vapor, which the researchers call a bottom-up approach. “By cloaking the freshly condensed nanoscale water droplets with oil, we are taking advantage of the inherent nature of phase-change and spreading phenomena,” Varanasi says.

“Our bottom-up approach of creating nanoscale emulsions is highly scalable owing to the simplicity of the process,” Anand says. “We have uncovered many new phenomena during this work. We have found how the presence of surfactant can change the oil and water interactions under such conditions, promoting oil spreading on water droplets and stabilizing them at the nanoscale.”

The team says that the approach should work with a variety of oils and surfactants, and now that the process has been identified, their findings “provide a kind of design guideline for someone to use” for a particular kind of application, Varanasi says.

“It’s such an important thing,” he says, because “foods and pharmaceuticals always have an expiration date,” and often that has to do with the instability of the emulsions in them. The experiments used a particular surfactant that is widely used, but many other varieties are available, including some that are approved for food-grade products.

In addition, Guha says, “we envision that you could use multiple liquids and make much more complex emulsions.” And besides being used in food, cosmetics, and drugs, the method could have other applications, such as in the oil and gas industry, where fluids such as the drilling “muds” sent down wells are also emulsions, Varanasi says.

The work was supported by the MIT Energy Initiative, the National Science Foundation, and a Society in Science fellowship. Anand, the co-author who was a postdoc at MIT, is now an assistant professor at the University of Illinois.

###

Written by David L. Chandler, MIT News Office

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Karl-Lydie Jean-Baptiste

MIT News Office

617-253-1682

Copyright © Massachusetts Institute of Technology

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Videos/Movies

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() New X-ray imaging technique to study the transient phases of quantum materials December 29th, 2022

New X-ray imaging technique to study the transient phases of quantum materials December 29th, 2022

![]() Solvent study solves solar cell durability puzzle: Rice-led project could make perovskite cells ready for prime time September 23rd, 2022

Solvent study solves solar cell durability puzzle: Rice-led project could make perovskite cells ready for prime time September 23rd, 2022

![]() Scientists prepare for the world’s smallest race: Nanocar Race II March 18th, 2022

Scientists prepare for the world’s smallest race: Nanocar Race II March 18th, 2022

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Nanomedicine

![]() New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Materials/Metamaterials/Magnetoresistance

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

![]() Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

![]() Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Food/Agriculture/Supplements

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() SMART researchers pioneer first-of-its-kind nanosensor for real-time iron detection in plants February 28th, 2025

SMART researchers pioneer first-of-its-kind nanosensor for real-time iron detection in plants February 28th, 2025

![]() Silver nanoparticles: guaranteeing antimicrobial safe-tea November 17th, 2023

Silver nanoparticles: guaranteeing antimicrobial safe-tea November 17th, 2023

Water

![]() Taking salt out of the water equation October 7th, 2022

Taking salt out of the water equation October 7th, 2022

Industrial

![]() Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

![]() Quantum interference in molecule-surface collisions February 28th, 2025

Quantum interference in molecule-surface collisions February 28th, 2025

![]() Boron nitride nanotube fibers get real: Rice lab creates first heat-tolerant, stable fibers from wet-spinning process June 24th, 2022

Boron nitride nanotube fibers get real: Rice lab creates first heat-tolerant, stable fibers from wet-spinning process June 24th, 2022

Grants/Sponsored Research/Awards/Scholarships/Gifts/Contests/Honors/Records

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

![]() New discovery aims to improve the design of microelectronic devices September 13th, 2024

New discovery aims to improve the design of microelectronic devices September 13th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||