Home > Press > Tiny probe could produce big improvements in batteries and fuel cells: A new method helps scientists get an atom's level understanding of electrochemical properties

|

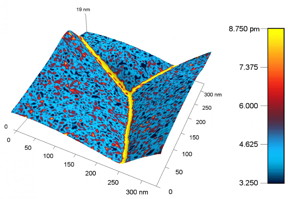

| This is a nanoscale map of the metal ceria produced with the new probe shows a higher response, represented by a yellow color, near the boundary between grains of metal. The higher response corresponds to a higher concentration of charged species. CREDIT: Ehsan Nasr Esfahani/University of Washington |

Abstract:

A team of American and Chinese researchers has developed a new tool that could aid in the quest for better batteries and fuel cells.

Tiny probe could produce big improvements in batteries and fuel cells: A new method helps scientists get an atom's level understanding of electrochemical properties

Washington, DC | Posted on June 1st, 2016Although battery technology has come a long way since Alessandro Volta first stacked metal discs in a "voltaic pile" to generate electricity, major improvements are still needed to meet the energy challenges of the future, such as powering electric cars and storing renewable energy cheaply and efficiently.

The key to the needed improvements likely lies in the nanoscale, said Jiangyu Li, a professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Washington in Seattle. The nanoscale is a realm so tiny that the movement of a few atoms or molecules can shift the landscape. Li and his colleagues have built a new window into this world to help scientists better understand how batteries really work. They describe their nanoscale probe in the Journal of Applied Physics, from AIP Publishing.

Batteries, and their close kin fuel cells, produce electricity through chemical reactions. The rates at which these reactions occur determine how fast the battery can charge, how much power it can provide, and how quickly it degrades.

Although the material in a battery electrode may look uniform to the human eye, to the atoms themselves, the environment is surprisingly diverse.

Near the surface and at the interfaces between materials, huge shifts in properties can occur -- and the shifts can affect the reaction rates in complex and difficult-to-understand ways.

Research in the last ten to fifteen years has revealed just how much local variations in material properties can affect the performance of batteries and other electrochemical systems, Li said.

The complex nanoscale landscape makes it tricky to fully understand what's going on, but "it may also create new opportunities to engineer materials properties so as to achieve quantum leaps in performance," he said.

To get a better understanding of how chemical reactions progress at the level of atoms and molecules, Li and his colleagues developed a nanoscale probe. The method is similar to atomic force microscopies: A tiny cantilever "feels" the material and builds a map of its properties with a resolution of nanometers or smaller.

In the case of the new electrochemical probe, the cantilever is heated with an electrical current, causing fluctuations in temperature and localized stress in the material beneath the probe. As a result, atoms and ions within the material move around, causing it to expand and contract. This expansion and contraction causes the cantilever to vibrate, which can be measured accurately using a laser beam shining on the top of the cantilever.

If a large concentration of ions or other charged particles exist in the vicinity of the probe tip, changes in their concentration will cause the material to deform further, similar to the way wood swells when it gets wet. The deformation is called Vegard strain.

Both Vegard strain and standard thermal expansion affect the vibration of the material, but in different ways. If the vibrations were like musical notes, the thermally-induced Vegard strain is like a harmonic overtone, ringing one octave higher than the note being played, Li explained.

The device identifies the Vegard strain-induced vibrations and can extrapolate the concentration of ions and electronic defects near the probe tip. The approach has advantages over other types of atomic microscopy that use voltage perturbations to generate a response, since voltage can produce many different kinds of responses, and it is difficult to isolate the part of the response related to shifts in ionic and electronic defect concentration. Thermal responses are easier to identify, although one disadvantage of the new system is that it can only probe rates slower than the heat transfer processes in the vicinity of the tip.

Still, the team believes the new method will offer researchers a valuable tool for studying electrochemical material properties at the nanoscale. They tested it by measuring the concentration of charged species in Sm-doped ceria and LiFePO4, important materials in solid oxide fuel cells and lithium batteries, respectively.

"The concentration of ionic and electronic species are often tied to important rate properties of electrochemical materials -- such as surface reactions, interfacial charge transfer, and bulk and surface diffusion -- that govern the device performance," Li said. "By measuring these properties locally on the nanoscale, we can build a much better understanding of how electrochemical systems really work, and thus how to develop new materials with much higher performance."

####

About American Institute of Physics

Journal of Applied Physics is an influential international journal publishing significant new experimental and theoretical results of applied physics research. See jap.aip.org.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

AIP Media Line

301-209-3090

Copyright © American Institute of Physics

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Materials/Metamaterials/Magnetoresistance

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

![]() Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

![]() Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Battery Technology/Capacitors/Generators/Piezoelectrics/Thermoelectrics/Energy storage

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Fuel Cells

![]() Deciphering local microstrain-induced optimization of asymmetric Fe single atomic sites for efficient oxygen reduction August 8th, 2025

Deciphering local microstrain-induced optimization of asymmetric Fe single atomic sites for efficient oxygen reduction August 8th, 2025

![]() Current and Future Developments in Nanomaterials and Carbon Nanotubes: Applications of Nanomaterials in Energy Storage and Electronics October 28th, 2022

Current and Future Developments in Nanomaterials and Carbon Nanotubes: Applications of Nanomaterials in Energy Storage and Electronics October 28th, 2022

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||