Home > Press > Unique 2-level cathode structure improves battery performance: Controlling surface chemistry could lead to higher-capacity, faster-charging batteries for electronics, vehicles, and energy-storage applications

|

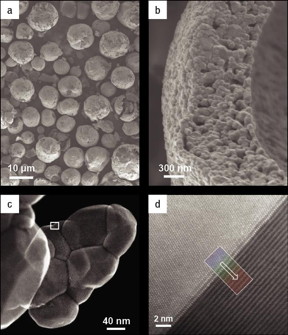

| This is a scanning and transmission electron micrographs of the cathode material at different magnifications. These images show that the 10-micron spheres (a) can be hollow and are composed of many smaller nanoscale particles (b). Chemical "fingerprinting" studies found that reactive nickel is preferentially located within the spheres' walls, with a protective manganese-rich layer on the outside. Studying ground up samples with intact interfaces between the nanoscale particles (c) revealed a slight offset of atoms at these interfaces that effectively creates "highways" for lithium ions to move in and out to reach the reactive nickel (d).

CREDIT: Brookhaven National Laboratory |

Abstract:

Building a better battery is a delicate balancing act. Increasing the amounts of chemicals whose reactions power the battery can lead to instability. Similarly, smaller particles can improve reactivity but expose more material to degradation. Now a team of scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory say they've found a way to strike a balance--by making a battery cathode with a hierarchical structure where the reactive material is abundant yet protected.

This 3-D rendering shows a hollow sphere about 10 millionths of a meter across made of a cathode material called NMC. Color-coding shows the uneven distribution of three key ingredients throughout the particle: manganese (blue), cobalt (red) and nickel (green). This uneven distribution allows the particle to store more energy during lithium-ion battery operation while protecting itself from degradation.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Unique 2-level cathode structure improves battery performance: Controlling surface chemistry could lead to higher-capacity, faster-charging batteries for electronics, vehicles, and energy-storage applications

Upton, NY | Posted on January 12th, 2016Test batteries incorporating this cathode material exhibited improved high-voltage cycling behavior--the kind you'd want for fast-charging electric vehicles and other applications that require high-capacity storage. The scientists describe the micro-to-nanoscale details of the cathode material in a paper published in the journal Nature Energy January 11, 2016.

"Our colleagues at Berkeley Lab were able to make a particle structure that has two levels of complexity where the material is assembled in a way that it protects itself from degradation," explained Brookhaven Lab physicist and Stony Brook University adjunct assistant professor Huolin Xin, who helped characterize the nanoscale details of the cathode material at Brookhaven Lab's Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN, https://www.bnl.gov/cfn/).

X-ray imaging performed by scientists at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at SLAC along with Xin's electron microscopy at CFN revealed spherical particles of the cathode material measuring millionths of meter, or microns, in diameter made up of lots of smaller, faceted nanoscale particles stacked together like bricks in a wall. The characterization techniques revealed important structural and chemical details that explain why these particles perform so well.

The lithium ion shuttle

Chemistry is at the heart of all lithium-ion rechargeable batteries, which power portable electronics and electric cars by shuttling lithium ions between positive and negative electrodes bathed in an electrolyte solution. As lithium moves into the cathode, chemical reactions generate electrons that can be routed to an external circuit for use. Recharging requires an external current to run the reactions in reverse, pulling the lithium ions out of the cathode and sending them to the anode.

Reactive metals like nickel have the potential to make great cathode materials--except that they are unstable and tend to undergo destructive side reactions with the electrolyte. So the Brookhaven, Berkeley, and SLAC battery team experimented with ways to incorporate nickel but protect it from these destructive side reactions.

They sprayed a solution of lithium, nickel, manganese, and cobalt mixed at a certain ratio through an atomizer nozzle to form tiny droplets, which then decomposed to form a powder. Repeatedly heating and cooling the powder triggered the formation of tiny nanosized particles and the self-assembly of these particles into the larger spherical, sometimes hollow, structures.

Using x-rays at SLAC's SSRL, the scientists made chemical "fingerprints" of the micron-scale structures. The synchrotron technique, called x-ray spectroscopy, revealed that the outer surface of the spheres was relatively low in nickel and high in unreactive manganese, while the interior was rich in nickel.

"The manganese layer forms an effective barrier, like paint on a wall, protecting the inner structure of the nickel-rich 'bricks' from the electrolyte," Xin said.

But how were the lithium ions still able to enter the material to react with the nickel? To find out, Xin's group at the CFN ground up the larger particles to form a powder composed of much smaller clumps of the nanoscale primary particles with some of the interfaces between them still intact.

"These samples show a small subset of the bricks that form the wall. We wanted to see how the bricks are put together. What kind of cement or mortar binds them? Are they layered together regularly or are they randomly oriented with spaces in between?" Xin said.

Nanoscale details explain improved performance

Using an aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope--a scanning transmission electron microscope outfitted with a pair of "glasses" to improve its vision--the scientists saw that the particles had facets, flat faces or sides like the cut edges of a crystal, which allowed them to pack tightly together to form coherent interfaces with no mortar or cement between the bricks. But there was a slight misfit between the two surfaces, with the atoms on one side of the interface being ever so slightly offset relative to the atoms on the adjoining particle.

"The packing of atoms at the interfaces between the tiny particles is slightly less dense than the perfect lattice within each individual particle, so these interfaces basically make a highway for lithium ions to go in and out," Xin said.

Like tiny smart cars, the lithium ions can move along these highways to reach the interior structure of the wall and react with the nickel, but much larger semi-truck-size electrolyte molecules can't get in to degrade the reactive material.

Using a spectroscopy tool within their microscope, the CFN scientists produced nanoscale chemical fingerprints that revealed there was some segregation of nickel and manganese even at the nanoscale, just as there was in the micron-scale structures.

"We don't know yet if this is functionally significant, but we think it could be beneficial and we want to study this further," Xin said. For example, he said, perhaps the material could be made at the nanoscale to have a manganese skeleton to stabilize the more reactive, less-stable nickel-rich pockets.

"That combination might give you a longer lifetime for the battery along with the higher charging capacity of the nickel," he said.

###

This work was supported by the Assistant Secretary for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Vehicle Technologies Office, of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Center for Functional Nanomaterials at Brookhaven Lab and the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource at SLAC are both DOE Office of Science User Facilities supported by the DOE Office of Science.

####

About Brookhaven National Laboratory

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

One of ten national laboratories overseen and primarily funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Brookhaven National Laboratory conducts research in the physical, biomedical, and environmental sciences, as well as in energy technologies and national security. Brookhaven Lab also builds and operates major scientific facilities available to university, industry and government researchers. Brookhaven is operated and managed for DOE's Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates, a limited-liability company founded by the Research Foundation for the State University of New York on behalf of Stony Brook University, the largest academic user of Laboratory facilities, and Battelle, a nonprofit applied science and technology organization.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Karen McNulty Walsh

631-344-8350

Peter Genzer

(631) 344-3174

Copyright © Brookhaven National Laboratory

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Imaging

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Videos/Movies

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Self Assembly

![]() Diamond glitter: A play of colors with artificial DNA crystals May 17th, 2024

Diamond glitter: A play of colors with artificial DNA crystals May 17th, 2024

![]() Liquid crystal templated chiral nanomaterials October 14th, 2022

Liquid crystal templated chiral nanomaterials October 14th, 2022

![]() Nanoclusters self-organize into centimeter-scale hierarchical assemblies April 22nd, 2022

Nanoclusters self-organize into centimeter-scale hierarchical assemblies April 22nd, 2022

![]() Atom by atom: building precise smaller nanoparticles with templates March 4th, 2022

Atom by atom: building precise smaller nanoparticles with templates March 4th, 2022

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Automotive/Transportation

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Battery Technology/Capacitors/Generators/Piezoelectrics/Thermoelectrics/Energy storage

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||