Home > Press > Imperfect graphene opens door to better fuel cells: Membrane could lead to fast-charging batteries for transportation

|

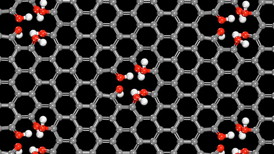

| The world’s thinnest proton channel: A few hydroxylated defect sites allow for simple and speedy proton transfer through pristine single-layer graphene. Credit: University of Minnesota |

Abstract:

The honeycomb structure of pristine graphene is beautiful, but Northwestern University scientists, together with collaborators from five other institutions, have discovered that if the graphene naturally has a few tiny holes in it, you have a proton-selective membrane that could lead to improved fuel cells.

Imperfect graphene opens door to better fuel cells: Membrane could lead to fast-charging batteries for transportation

Evanston, IL | Posted on March 18th, 2015A major challenge in fuel cell technology is efficiently separating protons from hydrogen. In a study of single-layer graphene and water, the Northwestern researchers found that slightly imperfect graphene shuttles protons -- and only protons -- from one side of the graphene membrane to the other in mere seconds. The membrane's speed and selectivity are much better than that of conventional membranes, offering engineers a new and simpler mechanism for fuel cell design.

"Imagine an electric car that charges in the same time it takes to fill a car with gas," said chemist Franz M. Geiger, who led the research. "And better yet -- imagine an electric car that uses hydrogen as fuel, not fossil fuels or ethanol, and not electricity from the power grid, to charge a battery. Our surprising discovery provides an electrochemical mechanism that could make these things possible one day."

Defective single-layer graphene, it turns out, produces a membrane that is the world's thinnest proton channel -- only one atom thick.

"We found if you just dial the graphene back a little on perfection, you will get the membrane you want," said Geiger, a professor of chemistry in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. "Everyone always strives to make really pristine graphene, but our data show if you want to get protons through, you need less perfect graphene."

The study will be published March 17 by the journal Nature Communications.

Geiger's research team included collaborators from Northwestern, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the University of Virginia, the University of Minnesota, Pennsylvania State University and the University of Puerto Rico.

In the atomic world of an aqueous solution, protons are pretty big, and scientists don't believe they can be driven through a single layer of chemically perfect graphene at room temperature. (Graphene is a form of elemental carbon composed of a single flat sheet of carbon atoms arranged in a repeating hexagonal, or honeycomb, lattice.)

When Geiger and his colleagues studied graphene exposed to water, they found that protons were indeed moving through the graphene. Using cutting-edge laser techniques, imaging methods and computer simulations, they set out to learn how.

The researchers discovered that naturally occurring defects in the graphene -- where a carbon atom is missing -- triggers a chemical merry-go-round where protons from water on one side of the membrane are shuttled to the other side in a few seconds. Their advanced computer simulations showed this occurs via a classic "bucket-line" mechanism first proposed in 1806.

The thinness of the atom-thick graphene makes it a quick trip for the protons, Geiger said. With conventional membranes, which are hundreds of nanometers thick, proton selection takes minutes -- much too long to be practical.

Next, the research team asked the question: How many carbon atoms do we need to knock out of the graphene layer to get protons to move through? Just a handful in a square micron area of graphene, the researchers calculated.

Removing a few carbon atoms results in others being highly reactive, which starts the proton shuttling process. Only protons go through the tiny holes, making the membrane very selective. (Conventional membranes are not very selective.)

"Our results will not make a fuel cell tomorrow, but it provides a mechanism for engineers to design a proton separation membrane that is far less complicated than what people had thought before," Geiger said. "All you need is slightly imperfect single-layer graphene."

###

The paper is titled "Aqueous Proton Transfer Across Single-Layer Graphene."

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Megan Fellman

847-491-3115

Copyright © Northwestern University

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

![]() Movie and images are available at:

Movie and images are available at:

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

![]() "Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

"Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

Videos/Movies

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

Graphene/ Graphite

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

![]() Breakthrough in proton barrier films using pore-free graphene oxide: Kumamoto University researchers achieve new milestone in advanced coating technologies September 13th, 2024

Breakthrough in proton barrier films using pore-free graphene oxide: Kumamoto University researchers achieve new milestone in advanced coating technologies September 13th, 2024

Discoveries

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

![]() "Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

"Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

Announcements

![]() Rice membrane extracts lithium from brines with greater speed, less waste October 3rd, 2025

Rice membrane extracts lithium from brines with greater speed, less waste October 3rd, 2025

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

![]() "Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

"Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

![]() Rice membrane extracts lithium from brines with greater speed, less waste October 3rd, 2025

Rice membrane extracts lithium from brines with greater speed, less waste October 3rd, 2025

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Automotive/Transportation

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Fuel Cells

![]() Deciphering local microstrain-induced optimization of asymmetric Fe single atomic sites for efficient oxygen reduction August 8th, 2025

Deciphering local microstrain-induced optimization of asymmetric Fe single atomic sites for efficient oxygen reduction August 8th, 2025

![]() Current and Future Developments in Nanomaterials and Carbon Nanotubes: Applications of Nanomaterials in Energy Storage and Electronics October 28th, 2022

Current and Future Developments in Nanomaterials and Carbon Nanotubes: Applications of Nanomaterials in Energy Storage and Electronics October 28th, 2022

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||