Home > Press > Cells studied in 3-D may reveal novel cancer targets

|

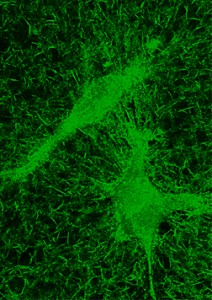

| Reflection confocal micrograph of collagen fibers of a 3D matrix with cancer cells embedded. Image by Stephanie Fraley/Wirtz Lab |

Abstract:

Showing movies in 3-D has produced a box-office bonanza in recent months. Could viewing cell behavior in three dimensions lead to important advances in cancer research? A new study led by Johns Hopkins University engineers indicates it may happen. Looking at cells in 3-D, the team members concluded, yields more accurate information that could help develop drugs to prevent cancer's spread.

by Mary Spiro

Cells studied in 3-D may reveal novel cancer targets

Baltimore, MD | Posted on October 4th, 2010"Finding out how cells move and stick to surfaces is critical to our understanding of cancer and other diseases. But most of what we know about these behaviors has been learned in the 2-D environment of Petri dishes," said Denis Wirtz, director of the Johns Hopkins Engineering in Oncology Center and principal investigator of the study. "Our study demonstrates for the first time that the way cells move inside a three-dimensional environment, such as the human body, is fundamentally different from the behavior we've seen in conventional flat lab dishes. It's both qualitatively and quantitatively different."

One implication of this discovery is that the results produced by a common high-speed method of screening drugs to prevent cell migration on flat substrates are, at best, misleading, said Wirtz, who also is the Theophilus H. Smoot Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at Johns Hopkins. This is important because cell movement is related to the spread of cancer, Wirtz said. "Our study identified possible targets to dramatically slow down cell invasion in a three-dimensional matrix."

When cells are grown in two dimensions, Wirtz said, certain proteins help to form long-lived attachments called focal adhesions on surfaces. Under these 2-D conditions, these adhesions can last several seconds to several minutes. The cell also develops a broad, fan-shaped protrusion called a lamella along its leading edges, which helps move it forward. "In 3-D, the shape is completely different," Wirtz said. "It is more spindlelike with two pointed protrusions at opposite ends. Focal adhesions, if they exist at all, are so tiny and so short-lived they cannot be resolved with microscopy."

The study's lead author, Stephanie Fraley, a Johns Hopkins doctoral student in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, said that the shape and mode of movement for cells in 2-D are merely an "artifact of their environment," which could produce misleading results when testing the effect of different drugs. "It is much more difficult to do 3-D cell culture than it is to do 2-D cell culture," Fraley said. "Typically, any kind of drug study that you do is conducted in 2D cell cultures before it is carried over into animal models. Sometimes, drug study results don't resemble the outcomes of clinical studies. This may be one of the keys to understanding why things don't always match up."

Fraley's faculty supervisor, Wirtz, suggested that part of the reason for the disconnect could be that even in studies that are called 3-D, the top of the cells are still located above the matrix. "Most of the work has been for cells only partially embedded in a matrix, which we call 2.5-D," he said. "Our paper shows the fundamental difference between 3-D and 2.5-D: Focal adhesions disappear, and the role of focal adhesion proteins in regulating cell motility becomes different."

Wirtz added that "because loss of adhesion and enhanced cell movement are hallmarks of cancer," his team's findings should radically alter the way cells are cultured for drug studies. For example, the team found that in a 3-D environment, cells possessing the protein zyxin would move in a random way, exploring their local environment. But when the gene for zyxin was disabled, the cells traveled in a rapid and persistent, almost one-dimensional pathway far from their place of origin.

Fraley said such cells might even travel back down the same pathways they had already explored. "It turns out that zyxin is misregulated in many cancers," Fraley said. Therefore, she added, an understanding of the function of proteins like zyxin in a 3-D cell culture is critical to understanding how cancer spreads, or metastasizes. "Of course tumor growth is important, but what kills most cancer patients is metastasis," she said.

To study cells in 3-D, the team coated a glass slide with layers of collagen-enriched gel several millimeters thick. Collagen, the most abundant protein in the body, forms a network in the gel of cross-linked fibers similar to the natural extracellular matrix scaffold upon which cells grow in the body. The researchers then mixed cells into the gel before it set. Next, they used an inverted confocal microscope to view from below the cells traveling within the gel matrix. The displacement of tiny beads embedded in the gel was used to show movement of the collagen fibers as the cells extended protrusions in both directions and then pulled inward before releasing one fiber and propelling themselves forward.

Fraley compared the movement of the cells to a person trying to maneuver through an obstacle course crisscrossed with bungee cords. "Cells move by extending one protrusion forward and another backward, contracting inward, and then releasing one of the contacts before releasing the other," she said. Ultimately, the cell moves in the direction of the contact released last.

When a cell moves along on a 2-D surface, the underside of the cell is in constant contact with a surface, where it can form many large and long-lasting focal adhesions. Cells moving in 3-D environments, however, only make brief contacts with the network of collagen fibers surrounding them-contacts too small to see and too short-lived to even measure, the researchers observed.

"We think the same focal adhesion proteins identified in 2-D situations play a role in 3-D motility, but their role in 3-D is completely different and unknown," Wirtz said. "There is more we need to discover."

Fraley said her future research will be focused specifically on the role of mechanosensory proteins like zyxin on motility, as well as how factors such as gel matrix pore size and stiffness affect cell migration in 3-D.

Co-investigators on this research from Washington University in St. Louis were Gregory D. Longmore, a professor of medicine, and his postdoctoral fellow Yunfeng Feng, both of whom are affiliated with the university's BRIGHT Institute. Longmore and Wirtz lead one of three core projects that are the focus of the Johns Hopkins Engineering in Oncology Center, a National Cancer Institute-funded Physical Sciences in Oncology Center. Additional Johns Hopkins authors, all from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, were Alfredo Celedon, a recent doctoral recipient; Ranjini Krishnamurthy, a recent bachelor's degree recipient; and Dong-Hwee Kim, a current doctoral student.

Funding for the research was provided by the National Cancer Institute. This study, a collaboration with researchers at Washington University in St. Louis, appeared in the June issue of Nature Cell Biology.

####

About Johns Hopkins Institute for NanoBioTechnology

The Johns Hopkins Institute for NanoBioTechnology (INBT) at Johns Hopkins University brings together researchers from: Bloomberg School of Public Health, Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, School of Medicine, Applied Physics Laboratory and Whiting School of Engineering to create new knowledge and new technologies at the interface of nanoscience and medicine.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

For media inquiries contact Mary Spiro at or call 410 516-4802

Copyright © Johns Hopkins Institute for NanoBioTechnology

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Academic/Education

![]() Rice University launches Rice Synthetic Biology Institute to improve lives January 12th, 2024

Rice University launches Rice Synthetic Biology Institute to improve lives January 12th, 2024

![]() Multi-institution, $4.6 million NSF grant to fund nanotechnology training September 9th, 2022

Multi-institution, $4.6 million NSF grant to fund nanotechnology training September 9th, 2022

Nanomedicine

![]() New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Nanobiotechnology

![]() New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Ben-Gurion University of the Negev researchers several steps closer to harnessing patient's own T-cells to fight off cancer June 6th, 2025

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev researchers several steps closer to harnessing patient's own T-cells to fight off cancer June 6th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||