|

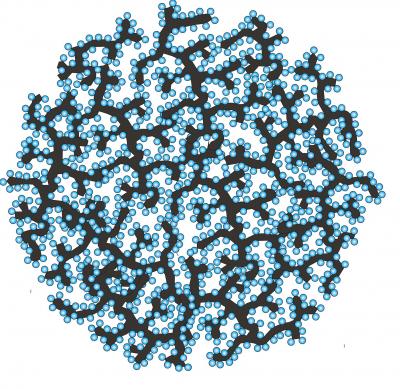

| This schematic shows a silicon-carbon nanocomposite granule formed through a hierarchical bottom-up assembly process. Annealed carbon black particles are coated by silicon nanoparticles and then assembled into rigid spheres with open interconnected internal channels. Credit: Courtesy of Gleb Yushin |

Abstract:

High-Performance Lithium-Ion Anode Uses "Bottom Up, Self-Assembled" Nanocomposite Materials to Increase Capacity

By John Toon

Battery boost

Atlanta, GA | Posted on March 15th, 2010A new high-performance anode structure based on silicon-carbon nanocomposite materials could significantly improve the performance of lithium-ion batteries used in a wide range of applications from hybrid vehicles to portable electronics.

Produced with a "bottom-up" self-assembly technique, the new structure takes advantage of nanotechnology to fine-tune its materials properties, addressing the shortcomings of earlier silicon-based battery anodes. The simple, low-cost fabrication technique was designed to be easily scaled up and compatible with existing battery manufacturing.

Details of the new self-assembly approach were published online in the journal Nature Materials on March 14.

"Development of a novel approach to producing hierarchical anode or cathode particles with controlled properties opens the door to many new directions for lithium-ion battery technology," said Gleb Yushin, an assistant professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. "This is a significant step toward commercial production of silicon-based anode materials for lithium-ion batteries."

The popular and lightweight batteries work by transferring lithium ions between two electrodes - a cathode and an anode - through a liquid electrolyte. The more efficiently the lithium ions can enter the two electrodes during charge and discharge cycles, the larger the battery's capacity will be.

Existing lithium-ion batteries rely on anodes made from graphite, a form of carbon. Silicon-based anodes theoretically offer as much as a ten-fold capacity improvement over graphite, but silicon-based anodes have so far not been stable enough for practical use.

Graphite anodes use particles ranging in size from 15 to 20 microns. If silicon particles of that size are simply substituted for the graphite, expansion and contraction as the lithium ions enter and leave the silicon creates cracks that quickly cause the anode to fail.

The new nanocomposite material solves that degradation problem, potentially allowing battery designers to tap the capacity advantages of silicon. That could facilitate higher power output from a given battery size - or allow a smaller battery to produce a required amount of power.

"At the nanoscale, we can tune materials properties with much better precision than we can at traditional size scales," said Yushin. "This is an example of where having nanoscale fabrication techniques leads to better materials."

Electrical measurements of the new composite anodes in small coin cells showed they had a capacity more than five times greater than the theoretical capacity of graphite.

Fabrication of the composite anode begins with formation of highly conductive branching structures - similar to the branches of a tree - made from carbon black nanoparticles annealed in a high-temperature tube furnace. Silicon nanospheres with diameters of less than 30 nanometers are then formed within the carbon structures using a chemical vapor deposition process. The silicon-carbon composite structures resemble "apples hanging on a tree."

Using graphitic carbon as an electrically-conductive binder, the silicon-carbon composites are then self-assembled into rigid spheres that have open, interconnected internal pore channels. The spheres, formed in sizes ranging from 10 to 30 microns, are used to form battery anodes. The relatively large composite powder size - a thousand times larger than individual silicon nanoparticles - allows easy powder processing for anode fabrication.

The internal channels in the silicon-carbon spheres serve two purposes. They admit liquid electrolyte to allow rapid entry of lithium ions for quick battery charging, and they provide space to accommodate expansion and contraction of the silicon without cracking the anode. The internal channels and nanometer-scale particles also provide short lithium diffusion paths into the anode, boosting battery power characteristics.

The size of the silicon particles is controlled by the duration of the chemical vapor deposition process and the pressure applied to the deposition system. The size of the carbon nanostructure branches and the size of the silicon spheres determine the pore size in the composite.

Production of the silicon-carbon composites could be scaled up as a continuous process amenable to ultra high-volume powder manufacturing, Yushin said. Because the final composite spheres are relatively large when they are fabricated into anodes, the self-assembly technique avoids the potential health risks of handling nanoscale powders, he added.

Once fabricated, the nanocomposite anodes would be used in batteries just like conventional graphite structures. That would allow battery manufacturers to adopt the new anode material without making dramatic changes in production processes.

So far, the researchers have tested the new anode through more than a hundred charge-discharge cycles. Yushin believes the material would remain stable for thousands of cycles because no degradation mechanisms have become apparent.

"If this technology can offer a lower cost on a capacity basis, or lighter weight compared to current techniques, this will help advance the market for lithium batteries," he said. "If we are able to produce less expensive batteries that last for a long time, this could also facilitate the adoption of many 'green' technologies, such as electric vehicles or solar cells."

In addition to Yushin, the paper's authors included Alexandre Magasinki, Patrick Dixon and Benjamin Hertzberg - all from Georgia Tech - and Alexander Kvit from the Materials Science Center and Materials Science Department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Jorge Ayala from Superior Graphite. The paper also acknowledges the contributions of Alexander Alexeev at Georgia Tech and Igor Luzinov from Clemson University.

The research was partially supported by a Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grant from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to Chicago-based Superior Graphite and Atlanta-based Streamline Nanotechnologies, Inc.

####

About Georgia Institute of Technology

The Georgia Institute of Technology is one of the nation's top research universities, distinguished by its commitment to improving the human condition through advanced science and technology.

Georgia Tech's campus occupies 400 acres in the heart of the city of Atlanta, where 20,000 undergraduate and graduate students receive a focused, technologically based education.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

John Toon

404-894-6986

Abby Vogel

404-385-3364

Copyright © Georgia Institute of Technology

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Academic/Education

![]() Rice University launches Rice Synthetic Biology Institute to improve lives January 12th, 2024

Rice University launches Rice Synthetic Biology Institute to improve lives January 12th, 2024

![]() Multi-institution, $4.6 million NSF grant to fund nanotechnology training September 9th, 2022

Multi-institution, $4.6 million NSF grant to fund nanotechnology training September 9th, 2022

Self Assembly

![]() Diamond glitter: A play of colors with artificial DNA crystals May 17th, 2024

Diamond glitter: A play of colors with artificial DNA crystals May 17th, 2024

![]() Liquid crystal templated chiral nanomaterials October 14th, 2022

Liquid crystal templated chiral nanomaterials October 14th, 2022

![]() Nanoclusters self-organize into centimeter-scale hierarchical assemblies April 22nd, 2022

Nanoclusters self-organize into centimeter-scale hierarchical assemblies April 22nd, 2022

![]() Atom by atom: building precise smaller nanoparticles with templates March 4th, 2022

Atom by atom: building precise smaller nanoparticles with templates March 4th, 2022

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Automotive/Transportation

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Battery Technology/Capacitors/Generators/Piezoelectrics/Thermoelectrics/Energy storage

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||