Home > Press > Scientists break the link between a quantum material's spin and orbital states: The advance opens a path toward a new generation of logic and memory devices based on orbitronics that could be 10,000 times faster than today's

|

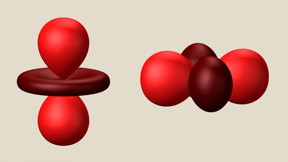

| These balloon-and-disc shapes represent an electron orbital -- a fuzzy electron cloud around an atom's nucleus -- in two different orientations. Scientists hope to someday use variations in the orientations of orbitals as the 0s and 1s needed to make computations and store information in computer memories, a system known as orbitronics. A SLAC study shows it's possible to separate these orbital orientations from electron spin patterns, a key step for independently controlling them in a class of materials that's the cornerstone of modern information technology. CREDIT Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory |

Abstract:

In designing electronic devices, scientists look for ways to manipulate and control three basic properties of electrons: their charge; their spin states, which give rise to magnetism; and the shapes of the fuzzy clouds they form around the nuclei of atoms, which are known as orbitals.

Scientists break the link between a quantum material's spin and orbital states: The advance opens a path toward a new generation of logic and memory devices based on orbitronics that could be 10,000 times faster than today's

Sanford, CA | Posted on May 15th, 2020Until now, electron spins and orbitals were thought to go hand in hand in a class of materials that's the cornerstone of modern information technology; you couldn't quickly change one without changing the other. But a study at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory shows that a pulse of laser light can dramatically change the spin state of one important class of materials while leaving its orbital state intact.

The results suggest a new path for making a future generation of logic and memory devices based on "orbitronics," said Lingjia Shen, a SLAC research associate and one of the lead researchers for the study.

"What we're seeing in this system is the complete opposite of what people have seen in the past," Shen said. "It raises the possibility that we could control a material's spin and orbital states separately, and use variations in the shapes of orbitals as the 0s and 1s needed to make computations and store information in computer memories."

The international research team, led by Joshua Turner, a SLAC staff scientist and investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Science (SIMES), reported their results this week in Physical Review B Rapid Communications.

An intriguing, complex material

The material the team studied was a manganese oxide-based quantum material known as NSMO, which comes in extremely thin crystalline layers. It's been around for three decades and is used in devices where information is stored by using a magnetic field to switch from one electron spin state to another, a method known as spintronics. NSMO is also considered a promising candidate for making future computers and memory storage devices based on skyrmions, tiny particle-like vortexes created by the magnetic fields of spinning electrons.

But this material is also very complex, said Yoshinori Tokura, director of the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science in Japan, who was also involved in the study.

"Unlike semiconductors and other familiar materials, NSMO is a quantum material whose electrons behave in a cooperative, or correlated, manner, rather than independently as they usually do," he said. "This makes it hard to control one aspect of the electrons' behavior without affecting all the others."

One common way to investigate this type of material is to hit it with laser light to see how its electronic states respond to an injection of energy. That's what the research team did here. They observed the material's response with X-ray laser pulses from SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS).

One melts, the other doesn't

What they expected to see was that orderly patterns of electron spins and orbitals in the material would be thrown into total disarray, or "melted," as they absorbed pulses of near-infrared laser light.

But to their surprise, only the spin patterns melted, while the orbital patterns stayed intact, Turner said. The normal coupling between the spin and orbital states had been completely broken, he said, which is a challenging thing to do in this type of correlated material and had not been observed before.

Tokura said, "Usually only a tiny application of photoexcitation destroys everything. Here, they were able to keep the electron state that is most important for future devices - the orbital state - undamaged. This is a nice new addition to the science of orbitronics and correlated electrons."

Much as electron spin states are switched in spintronics, electron orbital states could be switched to provide a similar function. These orbitronic devices could, in theory, operate 10,000 faster than spintronic devices, Shen said.

Switching between two orbital states could be made possible by using short bursts of terahertz radiation, rather than the magnetic fields used today, he said: "Combining the two could achieve much better device performance for future applications." The team is working on ways to do that.

###

Shen is now a postdoctoral researcher at Lund University in Sweden with a joint position with SIMES at SLAC. Scientists from the Advanced Light Source at DOE's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; the Swiss Light Source at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Sweden; the University of Tokyo and University of Tsukuba in Japan; and the University of Chicago also contributed to this research. Both LCLS and the Advanced Light Source are DOE Office of Science user facilities, and major support for the study came from the DOE Office of Science. Turner's research was supported through the DOE Office of Science Early Career Research Program.

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Glennda Chui

510-507-2766

Copyright © SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

![]() Citation: Lingjia Shen et al., Physical Review B Rapid Communications 101, 201103(R), 12 May 2020:

Citation: Lingjia Shen et al., Physical Review B Rapid Communications 101, 201103(R), 12 May 2020:

| Related News Press |

Quantum Physics

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Physics

![]() Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Spintronics

![]() Quantum materials: Electron spin measured for the first time June 9th, 2023

Quantum materials: Electron spin measured for the first time June 9th, 2023

Chip Technology

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

Quantum nanoscience

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||