Home > Press > Scientists uncover origin of high-temperature superconductivity in copper-oxide compound: Analysis of thousands of samples reveals that the compound becomes superconducting at an unusually high temperature because local electron pairs form a 'superfluid' that flows without resist

|

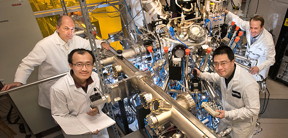

| (Clockwise from left) Brookhaven Lab physicists Ivan Bozovic, Anthony Bollinger, and Jie Wu, and postdoctoral researcher Xi He with the atomic layer-by-layer molecular beam epitaxy system used to synthesize more than 2,500 thin films of a copper-oxide compound called LSCO. The team studied LSCO to understand why it can become superconducting at a much higher temperature than the ultra-chilled temperatures required by conventional superconductors. |

Abstract:

Since the 1986 discovery of high-temperature superconductivity in copper-oxide compounds called cuprates, scientists have been trying to understand how these materials can conduct electricity without resistance at temperatures hundreds of degrees above the ultra-chilled temperatures required by conventional superconductors. Finding the mechanism behind this exotic behavior may pave the way for engineering materials that become superconducting at room temperature. Such a capability could enable lossless power grids, more affordable magnetically levitated transit systems, and powerful supercomputers, and change the way energy is produced, transmitted, and used globally.

Scientists uncover origin of high-temperature superconductivity in copper-oxide compound: Analysis of thousands of samples reveals that the compound becomes superconducting at an unusually high temperature because local electron pairs form a 'superfluid' that flows without resist

Upton, NY | Posted on August 19th, 2016Now, physicists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory have an explanation for why the temperature at which cuprates become superconducting is so high. After growing and analyzing thousands of samples of a cuprate known as LSCO for the four elements it contains (lanthanum, strontium, copper, and oxygen), they determined that this "critical" temperature is controlled by the density of electron pairs--the number of electron pairs per unit area. This finding, described in a Nature paper published August 17, challenges the standard theory of superconductivity, which proposes that the critical temperature depends instead on the strength of the electron pairing interaction.

"Solving the enigma of high-temperature superconductivity has been the focus of condensed matter physics for more than 30 years," said Ivan Bozovic, a senior physicist in Brookhaven Lab's Condensed Matter Physics and Materials Science Department who led the study. "Our experimental finding provides a basis for explaining the origin of high-temperature superconductivity in the cuprates--a basis that calls for an entirely new theoretical framework."

According to Bozovic, one of the reasons cuprates have been so difficult to study is because of the precise engineering required to generate perfect crystallographic samples that contain only the high-temperature superconducting phase.

"It is a materials science problem. Cuprates can have up to 50 atoms per unit cell and the elements can form hundreds of different compounds, likely resulting in a mixture of different phases," said Bozovic.

That's why Bozovic and his research team grew their more than 2,500 LSCO samples by using a custom-designed molecular beam epitaxy system that places single atoms onto a substrate, layer by layer. This system is equipped with advanced surface-science tools, such as those for absorption spectroscopy and electron diffraction, that provide real-time information about the surface morphology, thickness, chemical composition, and crystal structure of the resulting thin films.

"Monitoring these characteristics ensures there aren't any irregular geometries, defects, or precipitates from secondary phases in our samples," Bozovic explained.

In engineering the LSCO films, Bozovic chemically added strontium atoms, which produce mobile electrons that pair up in the copper-oxide layers where superconductivity occurs. This "doping" process allows LSCO and other cuprates--normally insulating materials--to become superconducting.

For this study, Bozovic added strontium in amounts beyond the doping level required to induce superconductivity. Earlier studies on this "overdoping" had indicated that the density of electron pairs decreases as the doping concentration is increased. Scientists had tried to explain this surprising experimental finding by attributing it to different electronic orders competing with superconductivity, or electron pair breaking caused by impurities or disorder in the lattice. For example, they had thought that geometrical defects, such as displaced or missing atoms, could be at play.

To test these explanations, Bozovic and his team measured the magnetic and electronic properties of their engineered LSCO films. They used a technique called mutual inductance to determine the magnetic penetration depth (the distance a magnetic field transmits through a superconductor), which indicates the density of electron pairs.

Their measurements established a precise linear relationship between the critical temperature and electron pair density: both continue to decrease as more dopant is added, until no electrons pair up at all, while the critical temperature drops to near-zero Kelvin (minus 459 degrees Fahrenheit). According to the standard understanding of metals and conventional superconductors, this result is unexpected because LSCO becomes more metallic the more it is overdoped.

"Disorder, phase separation, or electron pair breaking would have the reverse effect by introducing scattering that impedes the flow of electrons, thus making the material more resistive, i.e. less metallic," said Bozovic.

If Bozovic's team is correct that critical temperature is controlled by electron pair density, then it seems that small, local pairs of electrons are behind the high temperature at which cuprates become superconducting. Previous experiments have established that the size of electron pairs is much smaller in cuprates than in conventional superconductors, whose pairs are so large that they overlap. Understanding what interaction makes the electron pairs so small in cuprates is the next step in the quest to solve the mystery of high-temperature superconductivity.

###

Bozovic's team included Brookhaven physicists Anthony Bollinger and Jie Wu, supported by funding provided by DOE's Office of Science, and postdoctoral researcher Xi He, supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

####

About Brookhaven National Laboratory

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Ariana Tantillo

631-344-2347

Copyright © Brookhaven National Laboratory

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Superconductivity

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Videos/Movies

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

Physics

![]() Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

![]() Magnetism in new exotic material opens the way for robust quantum computers June 4th, 2025

Magnetism in new exotic material opens the way for robust quantum computers June 4th, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||