Home > Press > New form of electron-beam imaging can see elements that are 'invisible' to common methods: Berkeley Lab-pioneered 'MIDI-STEM' produces high-resolution views of lightweight atoms

|

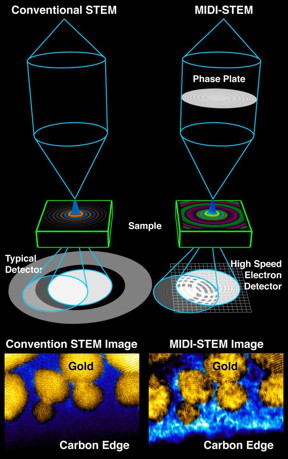

| This representation shows a Berkeley Lab-developed technique called MIDI-STEM (at right), and conventional STEM (at left) that does not use a ringed object called a phase plate. In MIDI-STEM, an interference pattern (bottom right) introduced by the phase plate (top right) interacts with the electron beam before it travels through a sample (the blue wave in the center). As the phase of the sample (the distance between the peaks and valleys of the blue wave) changes, the electrons passing through the sample are affected and can be measured as a pattern (bottom right). CREDIT: Colin Ophus/Berkeley Lab, Nature Communications: 10.1038/ncomms10719 |

Abstract:

Electrons can extend our view of microscopic objects well beyond what's possible with visible light--all the way to the atomic scale. A popular method in electron microscopy for looking at tough, resilient materials in atomic detail is called STEM, or scanning transmission electron microscopy, but the highly-focused beam of electrons used in STEM can also easily destroy delicate samples.

New form of electron-beam imaging can see elements that are 'invisible' to common methods: Berkeley Lab-pioneered 'MIDI-STEM' produces high-resolution views of lightweight atoms

Berkeley, CA | Posted on March 3rd, 2016This is why using electrons to image biological or other organic compounds, such as chemical mixes that include lithium--a light metal that is a popular element in next-generation battery research--requires a very low electron dose.

Scientists at the Department of Energy'sc Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have developed a new imaging technique, tested on samples of nanoscale gold and carbon, that greatly improves images of light elements using fewer electrons.

The newly demonstrated technique, dubbed MIDI-STEM, for matched illumination and detector interferometry STEM, combines STEM with an optical device called a phase plate that modifies the alternating peak-to-trough, wave-like properties (called the phase) of the electron beam.

This phase plate modifies the electron beam in a way that allows subtle changes in a material to be measured, even revealing materials that would be invisible in traditional STEM imaging.

Another electron-based method, which researchers use to determine the detailed structure of delicate, frozen biological samples, is called cryo-electron microscopy, or cryo-EM. While single-particle cryo-EM is a powerful tool--it was named as science journal Nature's 2015 Method of the Year --it typically requires taking an average over many identical samples to be effective. Cryo-EM is generally not useful for studying samples with a mixture of heavy elements (for example, most types of metals) and light elements like oxygen and carbon.

"The MIDI-STEM method provides hope for seeing structures with a mixture of heavy and light elements, even when they are bunched closely together," said Colin Ophus, a project scientist at Berkeley Lab's Molecular Foundry and lead author of a study, published Feb. 29 in Nature Communications, that details this method.

If you take a heavy-element nanoparticle and add molecules to give it a specific function, conventional techniques don't provide an easy, clear way to see the areas where the nanoparticle and added molecules meet.

"How are they aligned? How are they oriented?" Ophus asked. "There are so many questions about these systems, and because there wasn't a way to see them, we couldn't directly answer them."

While traditional STEM is effective for "hard" samples that can stand up to intense electron beams, and cryo-EM can image biological samples, "We can do both at once" with the MIDI-STEM technique, said Peter Ercius, a Berkeley Lab staff scientist at the Molecular Foundry and co-author of the study.

The phase plate in the MIDI-STEM technique allows a direct measure of the phase of electrons that are weakly scattered as they interact with light elements in the sample. These measurements are then used to construct so-called phase-contrast images of the elements. Without this phase information, the high-resolution images of these elements would not be possible.

In this study, the researchers combined phase plate technology with one of the world's highest resolution STEMs, at Berkeley Lab's Molecular Foundry, and a high-speed electron detector.

They produced images of samples of crystalline gold nanoparticles, which measured several nanometers across, and the super-thin film of amorphous carbon that the particles sat on. They also performed computer simulations that validated what they saw in the experiment.

The phase plate technology was developed as part of a Berkeley Lab Laboratory Directed Research and Development grant in collaboration with Ben McMorran at University of Oregon.

The MIDI-STEM technique could prove particularly useful for directly viewing nanoscale objects with a mixture of heavy and light materials, such as some battery and energy-harvesting materials, that are otherwise difficult to view together at atomic resolution.

It also might be useful in revealing new details about important two-dimensional proteins, called S-layer proteins, that could serve as foundations for engineered nanostructures but are challenging to study in atomic detail using other techniques.

In the future, a faster, more sensitive electron detector could allow researchers to study even more delicate samples at improved resolution by exposing them to fewer electrons per image.

"If you can lower the electron dose you can tilt beam-sensitive samples into many orientations and reconstruct the sample in 3-D, like a medical CT scan. There are also data issues that need to be addressed," Ercius said, as faster detectors will generate huge amounts of data. Another goal is to make the technique more "plug-and-play," so it is broadly accessible to other scientists.

###

Berkeley Lab's Molecular Foundry is a DOE Office of Science User Facility. Researchers from the University of Oregon, Gatan Inc. and Ulm University in Germany also participated in the study.

####

About Berkeley Lab

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world's most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab's scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

The DOE Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Glenn Roberts Jr.

510-486-5582

Copyright © Berkeley Lab

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Imaging

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Organic Electronics

![]() Unveiling the power of hot carriers in plasmonic nanostructures August 16th, 2024

Unveiling the power of hot carriers in plasmonic nanostructures August 16th, 2024

![]() Efficient and stable hybrid perovskite-organic light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 40 per cent July 5th, 2024

Efficient and stable hybrid perovskite-organic light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 40 per cent July 5th, 2024

![]() New organic molecule shatters phosphorescence efficiency records and paves way for rare metal-free applications July 5th, 2024

New organic molecule shatters phosphorescence efficiency records and paves way for rare metal-free applications July 5th, 2024

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Tools

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Battery Technology/Capacitors/Generators/Piezoelectrics/Thermoelectrics/Energy storage

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Nanobiotechnology

![]() New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Ben-Gurion University of the Negev researchers several steps closer to harnessing patient's own T-cells to fight off cancer June 6th, 2025

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev researchers several steps closer to harnessing patient's own T-cells to fight off cancer June 6th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||