|

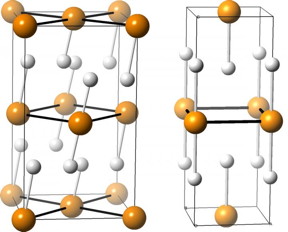

| These are illustrations of two compounds made from phosphorus atoms (orange) and hydrogen atoms (white). Such compounds are potential superconductors, and may form when phosphine is squeezed under extremely high pressures, according to University at Buffalo chemists who predicted the compounds' structures using XtalOpt, an open-source computer program created at UB.

Credit: Tyson Terpstra |

Abstract:

Phosphine is one of the newest materials to be named a superconductor, a material through which electricity can flow with zero resistance.

In 2015, scientists reported that they had liquefied the chemical and squeezed it under high pressure in a diamond vice to achieve superconductivity.

Now, a different group of researchers is providing insight into what may have happened to the phosphine as it underwent this intense compression.

University at Buffalo chemists say that according to their calculations, phosphine's superconductivity under pressure likely arose due to the compound decomposing into other chemical products that contain phosphorus and hydrogen.

"So it's probably a mix of these decomposition products -- and not phosphine itself -- that results in the superconductivity observed in experiments," says Eva Zurek, PhD, an associate professor of chemistry in the UB College of Arts and Sciences.

The findings could assist scientists in their quest to find or create new commercially feasible superconductors, which are sought after because the materials transmit energy with ultra-high efficiency, losing no energy and giving off no heat, she says.

"In experiments where high pressures are involved, it's difficult for scientists to characterize what materials they've created," Zurek says. "But understanding what's actually there is important because it gives us an idea of how we might go about making new superconducting compounds."

The new study was published on Jan. 16 in the Journal of the American Chemical Society as a Just Accepted Manuscript and will appear in a future print edition of the journal.

SUBHEAD: Breaking things down (literally)

At room temperature, phosphine is composed of one atom of phosphorus (P) and three of hydrogen (H).

But the UB researchers calculated that under pressure, PH3 becomes unstable and likely breaks down into structures that include PH2, PH and PH5, which are more stable.

Zurek's team used XtalOpt, an open-source computer program that one of her former students created, to understand which combinations of phosphorus and hydrogen were stable at pressures of up to 200 gigapascals -- nearly 2 million times the pressure of our atmosphere here on Earth, and similar to the pressure at which phosphine was squeezed in the diamond vice in the superconductor experiment.

SUBHEAD: The search for superconductors

One reason researchers are so keen on finding new superconductors is that the only known superconductors are superconducting only at extremely low temperatures (well below freezing), which complicates practical applications and makes their maintenance extremely difficult.

Interest in the field has intensified over the past year, since a team led by scientist Mikhail Eremets smashed previous temperature records by finding that a hydrogen and sulfur compound squeezed under 150 gigapascals of pressure was a superconductor at 203 degrees Kelvin, about -94 degrees Fahrenheit. That may seem cold, but it's a lot warmer than past thresholds.

Eremets and his colleagues were also the group that conducted the experiment on phosphine, with superconductivity observed at temperatures higher than 100 Kelvin (roughly -280 degrees Fahrenheit).

"Finding materials that are superconducting at high temperatures would revolutionize our electric power infrastructure, because virtually no energy would be wasted during transmission and distribution through superconducting wires," Zurek said. "In addition, superconducting magnets could be employed for high-speed levitating trains (maglev) that move more smoothly and efficiently than wheeled trains. These technologies exist nowadays, but the superconductors must be cooled to very low temperatures for them to work."

###

The new study by Zurek's team was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy (DOE) National Nuclear Security Administration via the Carnegie/DOE Alliance Center. The research was supported by UB's Center for Computational Research, an academic supercomputing facility.

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Charlotte Hsu

716-645-4655

Copyright © University at Buffalo

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

Magnetism/Magnons

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Superconductivity

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Materials/Metamaterials/Magnetoresistance

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

![]() Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

![]() Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||