Home > Press > Advance in quantum error correction: Protocol corrects virtually all errors in quantum memory, but requires little measure of quantum states

|

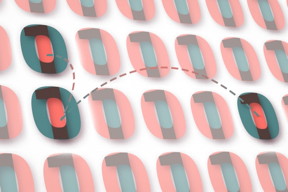

| A new quantum error correcting code requires measurements of only a few quantum bits at a time, to ensure consistency between one stage of a computation and the next.

Jose-Luis Olivares/MIT |

Abstract:

Quantum computers are largely theoretical devices that could perform some computations exponentially faster than conventional computers can. Crucial to most designs for quantum computers is quantum error correction, which helps preserve the fragile quantum states on which quantum computation depends.

Advance in quantum error correction: Protocol corrects virtually all errors in quantum memory, but requires little measure of quantum states

Cambridge, MA | Posted on May 27th, 2015The ideal quantum error correction code would correct any errors in quantum data, and it would require measurement of only a few quantum bits, or qubits, at a time. But until now, codes that could make do with limited measurements could correct only a limited number of errors -- one roughly equal to the square root of the total number of qubits. So they could correct eight errors in a 64-qubit quantum computer, for instance, but not 10.

In a paper they're presenting at the Association for Computing Machinery's Symposium on Theory of Computing in June, researchers from MIT, Google, the University of Sydney, and Cornell University present a new code that can correct errors afflicting a specified fraction of a computer's qubits, not just the square root of their number. And that fraction can be arbitrarily large, although the larger it is, the more qubits the computer requires.

"There were many, many different proposals, all of which seemed to get stuck at this square-root point," says Aram Harrow, an assistant professor of physics at MIT, who led the research. "So going above that is one of the reasons we're excited about this work."

Like a bit in a conventional computer, a qubit can represent 1 or 0, but it can also inhabit a state known as "quantum superposition," where it represents 1 and 0 simultaneously. This is the reason for quantum computers' potential advantages: A string of qubits in superposition could, in some sense, perform a huge number of computations in parallel.

Once you perform a measurement on the qubits, however, the superposition collapses, and the qubits take on definite values. The key to quantum algorithm design is manipulating the quantum state of the qubits so that when the superposition collapses, the result is (with high probability) the solution to a problem.

Baby, bathwater

But the need to preserve superposition makes error correction difficult. "People thought that error correction was impossible in the '90s," Harrow explains. "It seemed that to figure out what the error was you had to measure, and measurement destroys your quantum information."

The first quantum error correction code was invented in 1994 by Peter Shor, now the Morss Professor of Applied Mathematics at MIT, with an office just down the hall from Harrow's. Shor is also responsible for the theoretical result that put quantum computing on the map, an algorithm that would enable a quantum computer to factor large numbers exponentially faster than a conventional computer can. In fact, his error-correction code was a response to skepticism about the feasibility of implementing his factoring algorithm.

Shor's insight was that it's possible to measure relationships between qubits without measuring the values stored by the qubits themselves. A simple error-correcting code could, for instance, instantiate a single qubit of data as three physical qubits. It's possible to determine whether the first and second qubit have the same value, and whether the second and third qubit have the same value, without determining what that value is. If one of the qubits turns out to disagree with the other two, it can be reset to their value.

In quantum error correction, Harrow explains, "These measurement always have the form 'Does A disagree with B?' Except it might be, instead of A and B, A B C D E F G, a whole block of things. Those types of measurements, in a real system, can be very hard to do. That's why it's really desirable to reduce the number of qubits you have to measure at once."

Time embodied

A quantum computation is a succession of states of quantum bits. The bits are in some state; then they're modified, so that they assume another state; then they're modified again; and so on. The final state represents the result of the computation.

In their paper, Harrow and his colleagues assign each state of the computation its own bank of qubits; it's like turning the time dimension of the computation into a spatial dimension. Suppose that the state of qubit 8 at time 5 has implications for the states of both qubit 8 and qubit 11 at time 6. The researchers' protocol performs one of those agreement measurements on all three qubits, modifying the state of any qubit that's out of alignment with the other two.

Since the measurement doesn't reveal the state of any of the qubits, modification of a misaligned qubit could actually introduce an error where none existed previously. But that's by design: The purpose of the protocol is to ensure that errors spread through the qubits in a lawful way. That way, measurements made on the final state of the qubits are guaranteed to reveal relationships between qubits without revealing their values. If an error is detected, the protocol can trace it back to its origin and correct it.

It may be possible to implement the researchers' scheme without actually duplicating banks of qubits. But, Harrow says, some redundancy in the hardware will probably be necessary to make the scheme efficient. How much redundancy remains to be seen: Certainly, if each state of a computation required its own bank of qubits, the computer might become so complex as to offset the advantages of good error correction.

But, Harrow says, "Almost all of the sparse schemes started out with not very many logical qubits, and then people figured out how to get a lot more. Usually, it's been easier to increase the number of logical qubits than to increase the distance -- the number of errors you can correct. So we're hoping that will be the case for ours, too."

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Abby Abazorius

617-253-2709

Copyright © Massachusetts Institute of Technology

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

![]() Paper: “Sparse quantum codes from quantum circuits”:

Paper: “Sparse quantum codes from quantum circuits”:

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Physics

![]() Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

![]() Magnetism in new exotic material opens the way for robust quantum computers June 4th, 2025

Magnetism in new exotic material opens the way for robust quantum computers June 4th, 2025

Chip Technology

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Memory Technology

![]() Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Quantum Computing

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

![]() Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||