Home > Press > New method of producing nanomagnets for information technology

|

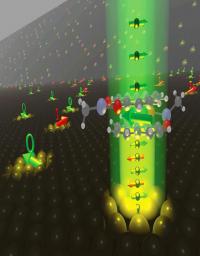

| The layer system of cobalt (bottom) and organic molecules can serve to store magnetic information that is indicated in the image by ones and zeros. The green and red arrows show the orientation of the spin.

Credit: Forschungszentrum Jülich |

Abstract:

An international team of researchers has found a new method of producing molecular magnets. Their thin layer systems made of cobalt and an organic material could pave the way for more powerful storage media as well as faster and more energy-efficient processors for information processing. The results of this research have been published in the current issue of the renowned journal Nature (DOI: 10.1038/nature11719).

New method of producing nanomagnets for information technology

Jülich, Germany | Posted on January 25th, 2013In order to boost the performance of computers and reduce their energy requirements, processors and storage media have become smaller and smaller over the years. However, this strategy is about to reach the limits imposed by physics. Components that are too small are unstable, making them unsuitable for secure data storage and processing. One reason is that even one atom more or less can change the physical properties of components significantly that consist of only a few atoms. However, the exact number and arrangement of atoms can hardly be controlled in metals and semiconductors - the materials that electronic device components are made of today.

One way out of this dilemma could be so-called "molecular electronics", with nanometre-scale components made up of molecules. Molecules consist of a fixed number of atoms, can be designed specifically for various purposes, and can be produced cost-effectively in an identical form over and over again. If the magnetic moment of the electron - the "spin" - is also exploited in addition to its electric charge, it looks as though it may even be possible to implement entirely new functionalities, such as non-volatile RAM or quantum computers.

Molecules for such "molecular spintronics" must have specific magnetic properties. However, these properties are very sensitive and, so far, frequently become lost if the molecules are attached to inorganic materials, which are required for conducting electric current. This is why a team of researchers from Forschungszentrum Jülich, the University of Göttingen, Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the USA, Ruđer Bošković Institute in Croatia and IISER Kolkata in India pursued a new strategy exploiting the unavoidable interactions between the molecules and their substrate in a targeted manner to produce a hybrid layer that exhibits molecular magnetism and has the desired properties.

The researchers applied zinc methyl phenalenyl, or ZMP for short, a small metalorganic molecule which in itself is not magnetic, onto a magnetic layer of cobalt. They showed that ZMP forms a magnetic "sandwich" only in combination with the cobalt surface and that it can be selectively switched back and forth between two magnetic states using magnetic fields. In this process, the electrical resistance of the layer system changes by more than 20 %. In order to produce these "magnetoresistive" effects necessary to store, process, and measure data in molecular systems, researchers often required temperatures well below -200 °C.

"Our system is highly magnetoresistive at a comparatively high temperature of -20 °C. This is a considerable step forward on the way to developing molecular data storage and logic elements that work at room temperature," says Jülich scientist Dr. Nicolae Atodiresei, a theoretical physicist at the Peter Grünberg Institute and the Institute for Advanced Simulation. He and his Jülich colleagues played a major role in developing a physical model that explains the properties of this material with the help of calculations on supercomputers at Forschungszentrum Jülich.

"We now know that it is necessary for the molecule to be practically flat," says Atodiresei. "Two molecules then form a stack and attach themselves closely to the cobalt surface. The cobalt and the lower molecules then form the magnetic sandwich, while the upper molecule serves as a 'spin filter' and allows primarily those electrons to pass whose spin is suitably oriented." The orientation can be controlled by means of a magnetic field, for example. On the basis of their findings, the researchers are now planning to further optimize their sandwich system and modify it in such a way that the filter effect can also be controlled by electrical fields or light pulses.

Original publication:

Interface-engineered templates for molecular spin memory devices; K.V. Raman et al.; Nature (issue of 24.1.2013); DOI: 10.1038/nature11719

####

About Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres

The Helmholtz Association is dedicated to pursuing the long-term research goals of state and society, and to maintaining and improving the livelihoods of the population. In order to do this, the Helmholtz Association carries out top-level research to identify and explore the major challenges facing society, science and the economy. Its work is divided into six strategic research fields: Energy; Earth and Environment; Health; Key Technologies; Structure of Matter; and Aeronautics, Space and Transport. The Helmholtz Association brings together 18 scientific-technical and biological-medical research centres. With some 32,698 employees and an annual budget of approximately €3.4 billion, the Helmholtz Association is Germany’s largest scientific organisation. Its work follows in the tradition of the great natural scientist Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-1894).

About Forschungszentrum Jülich…

... pursues cutting-edge interdisciplinary research addressing pressing issues facing society today, above all the energy supply of the future. With its competence in materials science and simulation and its expertise in physics, nanotechnology and information technology, as well as in the biosciences and brain research, Jülich is developing the basis for the key technologies of tomorrow. Forschungszentrum Jülich helps to solve the grand challenges facing society in the fields of energy and the environment, health, and information technology. With almost 5000 employees, Jülich – a member of the Helmholtz Association – is one of the large interdisciplinary research centres in Europe.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Angela Wenzik

science journalist

Forschungszentrum Jülich

Germany

49-246-161-6048

Dr. Nicolae Atodiresei

Quantum Theory of Materials (PGI-1/IAS-1)

Forschungszentrum

Jülich, Germany

+49 2461 61-2859

Copyright © Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

![]() Quantum Theory of Materials (PGI-1/IAS-1):

Quantum Theory of Materials (PGI-1/IAS-1):

![]() Massachusetts Institute of Technology:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology:

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

Chip Technology

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Memory Technology

![]() Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||