Home > Press > Tiny pores in graphene could give rise to membranes: New membranes may filter water or separate biological samples

|

|

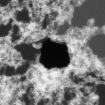

A high-resolution scanning transmission electron microscope image taken at Oak Ridge National Laboratory showing a large hole in the graphene (black region in the center). The image is 32 nm by 32 nm, hence the hole is about 10 nm in diameter. The white on the surface of the graphene is contamination, which is a recurring problem for anyone imaging graphene using this technique. Image courtesy of Juan-Carlos Idrobo |

Abstract:

Much has been made of graphene's exceptional qualities, from its ability to conduct heat and electricity better than any other material to its unparalleled strength: Worked into a composite material, graphene can repel bullets better than Kevlar. Previous research has also shown that pristine graphene — a microscopic sheet of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb pattern — is among the most impermeable materials ever discovered, making the substance ideal as a barrier film.

Tiny pores in graphene could give rise to membranes: New membranes may filter water or separate biological samples

Cambridge, MA | Posted on October 23rd, 2012But the material may not be as impenetrable as scientists have thought. By engineering relatively large membranes from single sheets of graphene grown by chemical vapor deposition, researchers from MIT, Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and elsewhere have found that the material bears intrinsic defects, or holes in its atom-sized armor. In experiments, the researchers found that small molecules like salts passed easily through a graphene membrane's tiny pores, while larger molecules were unable to penetrate.

The results, the researchers say, point not to a flaw in graphene, but to the possibility of promising applications, such as membranes that filter microscopic contaminants from water, or that separate specific types of molecules from biological samples.

"No one has looked for holes in graphene before," says Rohit Karnik, associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT. "There's a lot of chemical methods that can be used to modify these pores, so it's a platform technology for a new class of membranes."

Karnik and his colleagues, including researchers from the Indian Institute of Technology and King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, have published their results in the journal ACS Nano.

Karnik worked with MIT graduate student Sean O'Hern to look for materials "that could lead to not just incremental changes, but substantial leaps in terms of the way membranes perform." In particular, the team cast around for materials with two key attributes, high flux and tunability: that is, membranes that quickly filter fluids, but are also easily tailored to let certain molecules through while trapping others. The group settled on graphene, in part because of its extremely thin structure and its strength: A sheet of graphene is as thin as a single atom, but strong enough to let high volumes of fluids through without shredding apart.

The team set out to engineer a membrane spanning 25 square millimeters — a surface area that is large by graphene standards, holding about a quadrillion carbon atoms. They used graphene synthesized by chemical vapor deposition, borrowing on expertise from the research group of Jing Kong, the ITT Career Development Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering at MIT. The team then developed techniques to transfer the graphene sheet to a polycarbonate substrate dotted with holes.

Once the researchers successfully transferred the graphene, they began to experiment with the resulting membrane, exposing it to flowing water containing molecules of varying sizes. They theorized that if graphene were indeed impermeable, the molecules would be blocked from flowing across. However, experiments showed otherwise, as researchers observed salts flowing through the membrane.

As another test, the team exposed a copper foil with graphene grown on it to a chemical agent that dissolves copper. Instead of protecting the metal, graphene let the agent through, corroding the underlying copper. To test the size of the pores within graphene, the group attempted to filter water with larger molecules. It appeared that there was a limit to the size of the pores, as larger molecules were unable to pass through the membrane.

As a final experiment, Karnik and O'Hern observed the actual holes in the graphene membrane, looking at the material through a high-powered electron microscope at ORNL in collaboration with Juan-Carlos Idrobo. They found that pores ranged in size from about 1 to 12 nanometers — just wide enough to selectively let some small molecules through.

"Right now we know from this characterization how the graphene behaves, and what kind of intrinsic pores it has," Karnik says. "In some sense it's the first step to practically realizing graphene-based membranes."

Karnik adds that a near-term application for such membranes may include a portable sensor in which a layer of graphene "could shield the sensor from the environment," letting through only a molecule or contaminant of interest. Another use may be in drug delivery, with graphene, dotted with pores of a determined size, delivering therapies in a controlled release.

"We're right now in the process of transferring more graphene to different substrates and making holes of our own, making a viable membrane for water filtration," O'Hern says.

Scott Bunch, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Colorado, says the group's results are the first demonstration that graphene bears defects. The membrane developed by the group "has the potential to be a revolutionary membrane" that separates particles at the molecular scale.

"The issue that now needs to be addressed is whether one can discriminate between smaller molecules," Bunch says. "Once this happens, graphene membranes will eventually live up to the truly remarkable properties that they promise."

Other researchers involved in the work are Cameron Stewart, Michael Boutilier, Sreekar Bhaviripudi, Sarit Das, Tahar Laoui and Muataz Atieh. This work was funded by the King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals through the Center for Clean Water and Clean Energy at MIT and KFUPM, and was also supported by the ORNL ShaRE program.

Written by: Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Caroline McCall

MIT News Office

617-253-1682

Copyright © MIT

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Graphene/ Graphite

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

![]() Breakthrough in proton barrier films using pore-free graphene oxide: Kumamoto University researchers achieve new milestone in advanced coating technologies September 13th, 2024

Breakthrough in proton barrier films using pore-free graphene oxide: Kumamoto University researchers achieve new milestone in advanced coating technologies September 13th, 2024

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Nanomedicine

![]() New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Tools

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Water

![]() Taking salt out of the water equation October 7th, 2022

Taking salt out of the water equation October 7th, 2022

Nanobiotechnology

![]() New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Ben-Gurion University of the Negev researchers several steps closer to harnessing patient's own T-cells to fight off cancer June 6th, 2025

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev researchers several steps closer to harnessing patient's own T-cells to fight off cancer June 6th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||