Home > Press > Stanford-SLAC team uses X-ray imaging to observe running batteries in action

|

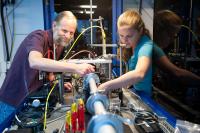

| Mike Toney and Johanna Nelson demonstrate the high-power transmission X-ray Microscope at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource.

Credit: Matt Beardsley/SLAC |

Abstract:

Most electric cars, from the Tesla Model S to the Nissan Leaf, run on rechargeable lithium-ion batteries - a pricey technology that accounts for more than half of the vehicle's total cost. One promising alternative is the lithium-sulfur battery, which can theoretically store five times more energy at a much lower cost.

Stanford-SLAC team uses X-ray imaging to observe running batteries in action

Stanford, CA | Posted on July 18th, 2012But lithium-sulfur technology has a major drawback: After a few dozen cycles of charging and discharging, the battery stops working.

"The cycle life of lithium-sulfur batteries is very short," said Johanna Nelson, a postdoctoral scholar at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory at Stanford University. "Typically, after a few tens of cycles the battery will die, so it isn't viable for electric vehicles, which require many thousands of cycles over a 10- or 20-year lifetime."

A typical lithium-sulfur battery consists of two electrodes - a lithium metal anode and a sulfur-carbon cathode - surrounded by a conductive fluid, or electrolyte. Several studies have attributed the battery's short cycle life to chemical reactions that deplete the cathode of sulfur.

But a recent study by Nelson and her colleagues is raising doubts about the validity of previous experiments. Using high-power X-ray imaging of an actual working battery, the Stanford-SLAC team discovered that sulfur particles in the cathode largely remain intact during discharge. Their results, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS), could help scientists find new ways to develop commercially viable lithium-sulfur batteries for electric vehicles.

"Based on previous experiments, we expected sulfur particles to completely disappear from the cathode when the battery discharges," said Nelson, the lead author of the JACS study. "Instead, we saw only negligible changes in the size of the particles, the exact opposite of what earlier studies found."

Nelson and her co-workers conducted their experiments at SLAC using two powerful imaging techniques: X-ray diffraction and transmission X-ray microscopy. The X-ray microscope enabled the researchers to take nanosize snapshots of individual sulfur particles before, during and after discharge - the first real-time imaging of a lithium-sulfur battery in operation.

"The standard way to do high-resolution imaging is with electron microscopes after the battery has partially discharged," Nelson said. "But electrons don't penetrate metal and plastic very well. With SLAC's X-ray microscope, we can actually see changes that are happening while the battery is running."

Pesky polysulfides

In lithium-sulfur batteries, an electric current is generated when lithium ions in the anode react with sulfur particles at the cathode during discharge. The byproducts of this chemical reaction are compounds known as lithium polysulfides.

Problems can arise when the polysulfides leak into the electrolyte and permanently bond with the lithium metal anode. "When that happens, all of the sulfur material in the polysulfides is lost," Nelson said. "It will never recycle. You don't want to lose active sulfur material every time the battery discharges. You want a battery that can be cycled multiple times."

Previous experiments also showed the formation of dilithium sulfide (Li2S) crystals during the discharge phase. "Crystalline Li2S and polysulfides can form a thin film that prevents the conduction of electrons and lithium ions," Nelson said. "The film acts as an insulating layer that can cause the battery to die."

Several studies using electron microscopes produced images of electrodes coated with polysulfides and crystalline Li2S, and cathodes depleted of sulfur. Those images led researchers to conclude that much of the sulfur had been chemically transformed into Li2S-polysulfide sheets that prevented the battery from operating.

Flawed findings

But according to Nelson and her colleagues, some of the previous studies were flawed. "The approach they were using was mistaken," Nelson said. "Typically, they would cycle the battery, disassemble it, wash away the electrolyte and then analyze it with X-ray diffraction or an electron microscope. But when you do that, you also wash away all of the polysulfides that are loosely trapped on the cathode. So when you image the cathode, you don't see any sulfur species at all."

The Stanford-SLAC team took a different approach. Researchers used the transmission X-ray microscope at SLAC to take multiple images of tiny sulfur particles every five minutes while the battery discharged. Each particle was a fraction of the size of a grain of sand. The results were clear: Every particle retained its basic shape and size throughout the discharge cycle.

"We expected the sulfur to completely disappear and form polysulfides in the electrolyte," Nelson said. "Instead we found that, for the most part, the particles stayed where they were and lost very little mass. They did form polysulfides, but most of those were trapped near the carbon-sulfur cathode. We didn't have to disassemble the battery or even stop it, because we could image the sulfur content while the device was operating."

X-ray diffraction yielded an additional surprise. "Based on previous experiments, we expected that crystalline Li2S would form at the end of the discharge cycle," she said. "But we did a very deep discharge and never saw any Li2S in its crystalline state."

Future research

The Stanford-SLAC study could open new avenues of research that could improve the performance of lithium-sulfur batteries, said co-author Michael Toney, head of the Materials Sciences Division at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource.

"Our study demonstrates the importance of using high-power X-ray technologies to study batteries while they are operating," Toney said. "From an engineering standpoint, it's valuable to know that relying on standard electron microscopy to test the fidelity of materials may give you deceptive results."

Several research labs are looking for new ways to trap polysulfides on the cathode. A variety of techniques have shown promise, including novel electrolytes and carbon nanotubes coated with sulfur.

But the polysulfide problem might not be as daunting as previous studies suggest.

"We found that very few of the polysulfides went into the electrolyte," Nelson said. "The carbon-sulfur cathode actually trapped them better than expected. But even a small amount of polysulfides will cause the battery to fail within 10 cycles. If scientists want to improve the cycle life of the battery, they need to prevent virtually all of the polysulfides from leaking into the electrolyte. If they really want to know what's going on inside the battery, they can't just use standard analysis. They need a technology that tells the whole story."

In addition to Nelson, the co-lead authors of the JACS study are SLAC postdoctoral researcher Sumohan Misra and Stanford doctoral student Yuan Yang.

The study is also co-authored by Yi Cui, an associate professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford and of photon science at SLAC; Hongjie Dai, a professor of chemistry at Stanford; graduate students Ariel Jackson and Hailiang Wang of Stanford; and Joy C. Andrews, a staff scientist at SLAC.

The research was supported by the Department of Energy, the Department of Defense and a Stanford Graduate Fellowship.

SLAC is a national laboratory operated by Stanford for the DOE. The study was conducted in cooperation with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Science, a Stanford-SLAC research partnership.

This article was written by Mark Shwartz, Precourt Institute for Energy at Stanford University.

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Mark Shwartz

650-723-9296

Copyright © Stanford University

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

![]() Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource:

Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource:

![]() Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Science:

Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Science:

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Imaging

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Tools

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Military

![]() Quantum engineers ‘squeeze’ laser frequency combs to make more sensitive gas sensors January 17th, 2025

Quantum engineers ‘squeeze’ laser frequency combs to make more sensitive gas sensors January 17th, 2025

![]() Chainmail-like material could be the future of armor: First 2D mechanically interlocked polymer exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength January 17th, 2025

Chainmail-like material could be the future of armor: First 2D mechanically interlocked polymer exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength January 17th, 2025

![]() Single atoms show their true color July 5th, 2024

Single atoms show their true color July 5th, 2024

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

Automotive/Transportation

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Battery Technology/Capacitors/Generators/Piezoelectrics/Thermoelectrics/Energy storage

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||