Home > Press > Cooling semiconductor by laser light

|

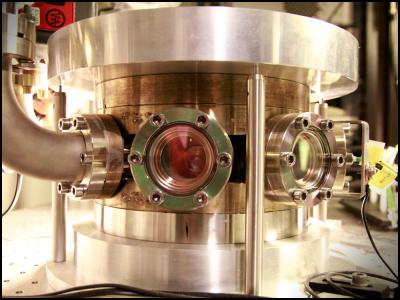

| The experiments themselves are carried out in this vacuum chamber. When the laser light hits the membrane, some of the light is reflected and some is absorbed and leads to a small heating of the membrane. The reflected light is reflected back again via a mirror in the experiment so that the light flies back and forth in this space and forms optical resonator (cavity). Changing the distance between the membrane and the mirror leads to a complex and fascinating interplay between the movement of the membrane, the properties of the semiconductor and the optical resonances and you can control the system so as to cool the temperature of the membrane fluctuations.

Credit: Niels Bohr Institute |

Abstract:

Researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute have combined two worlds - quantum physics and nano physics, and this has led to the discovery of a new method for laser cooling semiconductor membranes. Semiconductors are vital components in solar cells, LEDs and many other electronics, and the efficient cooling of components is important for future quantum computers and ultrasensitive sensors. The new cooling method works quite paradoxically by heating the material! Using lasers, researchers cooled membrane fluctuations to minus 269 degrees C. The results are published in the scientific journal, Nature Physics.

Cooling semiconductor by laser light

Copenhagen, Denmark | Posted on January 23rd, 2012"In experiments, we have succeeded in achieving a new and efficient cooling of a solid material by using lasers. We have produced a semiconductor membrane with a thickness of 160 nanometers and an unprecedented surface area of 1 by 1 millimeter. In the experiments, we let the membrane interact with the laser light in such a way that its mechanical movements affected the light that hit it. We carefully examined the physics and discovered that a certain oscillation mode of the membrane cooled from room temperature down to minus 269 degrees C, which was a result of the complex and fascinating interplay between the movement of the membrane, the properties of the semiconductor and the optical resonances," explains Koji Usami, associate professor at Quantop at the Niels Bohr Institute.

From gas to solid

Laser cooling of atoms has been practiced for several years in experiments in the quantum optical laboratories of the Quantop research group at the Niels Bohr Institute. Here researchers have cooled gas clouds of cesium atoms down to near absolute zero, minus 273 degrees C, using focused lasers and have created entanglement between two atomic systems. The atomic spin becomes entangled and the two gas clouds have a kind of link, which is due to quantum mechanics. Using quantum optical techniques, they have measured the quantum fluctuations of the atomic spin.

"For some time we have wanted to examine how far you can extend the limits of quantum mechanics - does it also apply to macroscopic materials? It would mean entirely new possibilities for what is called optomechanics, which is the interaction between optical radiation, i.e. light, and a mechanical motion," explains Professor Eugene Polzik, head of the Center of Excellence Quantop at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

But they had to find the right material to work with.

Lucky coincidence

In 2009, Peter Lodahl (who is today a professor and head of the Quantum Photonic research group at the Niels Bohr Institute) gave a lecture at the Niels Bohr Institute, where he showed a special photonic crystal membrane that was made of the semiconducting material gallium arsenide (GaAs). Eugene Polzik immediately thought that this nanomembrane had many advantageous electronic and optical properties and he suggested to Peter Lodahl's group that they use this kind of membrane for experiments with optomechanics. But this required quite specific dimensions and after a year of trying they managed to make a suitable one.

"We managed to produce a nanomembrane that is only 160 nanometers thick and with an area of more than 1 square millimetre. The size is enormous, which no one thought it was possible to produce," explains Assistant Professor Søren Stobbe, who also works at the Niels Bohr Institute.

Basis for new research

Now a foundation had been created for being able to reconcile quantum mechanics with macroscopic materials to explore the optomechanical effects.

Koji Usami explains that in the experiment they shine the laser light onto the nanomembrane in a vacuum chamber. When the laser light hits the semiconductor membrane, some of the light is reflected and the light is reflected back again via a mirror in the experiment so that the light flies back and forth in this space and forms an optical resonator. Some of the light is absorbed by the membrane and releases free electrons. The electrons decay and thereby heat the membrane and this gives a thermal expansion. In this way the distance between the membrane and the mirror is constantly changed in the form of a fluctuation.

"Changing the distance between the membrane and the mirror leads to a complex and fascinating interplay between the movement of the membrane, the properties of the semiconductor and the optical resonances and you can control the system so as to cool the temperature of the membrane fluctuations. This is a new optomechanical mechanism, which is central to the new discovery. The paradox is that even though the membrane as a whole is getting a little bit warmer, the membrane is cooled at a certain oscillation and the cooling can be controlled with laser light. So it is cooling by warming! We managed to cool the membrane fluctuations to minus 269 degrees C", Koji Usami explains.

"The potential of optomechanics could, for example, pave the way for cooling components in quantum computers. Efficient cooling of mechanical fluctuations of semiconducting nanomembranes by means of light could also lead to the development of new sensors for electric current and mechanical forces. Such cooling in some cases could replace expensive cryogenic cooling, which is used today and could result in extremely sensitive sensors that are only limited by quantum fluctuations," says Professor Eugene Polzik.

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Gertie Skaarup

(45) 35-32-53-20

Koji Usami

Associate Professor, Quantop

Niels Bohr Institute

University of Copenhagen

45-3532-5268

45-2829-7487

Eugene Polzi

Professor, Head of Quantop

Niels Bohr Institute

University of Copenhagen

45-3532-5424

45-2338-2045

Copyright © University of Copenhagen

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Display technology/LEDs/SS Lighting/OLEDs

![]() Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

![]() Efficient and stable hybrid perovskite-organic light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 40 per cent July 5th, 2024

Efficient and stable hybrid perovskite-organic light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 40 per cent July 5th, 2024

Chip Technology

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Quantum Computing

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

![]() Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Sensors

![]() Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Photonics/Optics/Lasers

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

Solar/Photovoltaic

![]() Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

![]() KAIST researchers introduce new and improved, next-generation perovskite solar cell November 8th, 2024

KAIST researchers introduce new and improved, next-generation perovskite solar cell November 8th, 2024

![]() Groundbreaking precision in single-molecule optoelectronics August 16th, 2024

Groundbreaking precision in single-molecule optoelectronics August 16th, 2024

![]() Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode: photoelectrochemical water-splitting hydrogen production January 12th, 2024

Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode: photoelectrochemical water-splitting hydrogen production January 12th, 2024

Quantum nanoscience

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||