Home > Press > JQI Physicists Demonstrate Coveted 'Spin-Orbit Coupling' for the First Time in Ultracold Atomic Gases

|

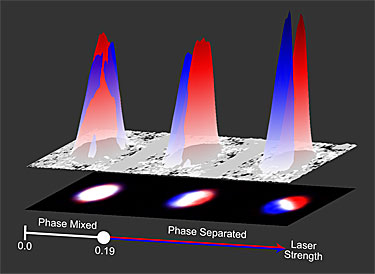

| In an ultracold gas of nearly 200,000 rubidium-87 atoms (shown as the large humps) the atoms can occupy one of two energy levels (represented as red and blue); lasers then link together these levels as a function of the atoms’ motion. At first atoms in the red and blue energy states occupy the same region (Phase Mixed), then at higher laser strengths, they separate into different regions (Phase Separated). Credit: Ian Spielman, JQI/NIST |

Abstract:

Physicists at the Joint Quantum Institute (JQI), a collaboration of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Maryland-College Park, have for the first time caused a gas of atoms to exhibit an important quantum phenomenon known as spin-orbit coupling. Their technique opens new possibilities for studying and better understanding fundamental physics and has potential applications to quantum computing, next-generation "spintronics" devices and even "atomtronic" devices built from ultracold atoms.

JQI Physicists Demonstrate Coveted 'Spin-Orbit Coupling' for the First Time in Ultracold Atomic Gases

Gaithersburg, MD | Posted on March 9th, 2011In the researchers' demonstration of spin-orbit coupling, two lasers allow an atom's motion to flip it between a pair of energy states. The new work, published in Nature*, demonstrates this effect for the first time in bosons, which make up one of the two major classes of particles. The same technique could be applied to fermions, the other major class of particles, according to the researchers. The special properties of fermions would make them ideal for studying new kinds of interactions between two particles—for example those leading to novel "p-wave" superconductivity, which may enable a long-sought form of quantum computing known as topological quantum computation.

In an unexpected development, the team also discovered that the lasers modified how the atoms interacted with each other and caused atoms in one energy state to separate in space from atoms in the other energy state.

One of the most important phenomena in quantum physics, spin-orbit coupling describes the interplay that can occur between a particle's internal properties and its external properties. In atoms, it usually describes interactions that only occur within an atom: how an electron's orbit around an atom's core (nucleus) affects the orientation of the electron's internal bar-magnet-like "spin." In semiconductor materials such as gallium arsenide, spin-orbit coupling is an interaction between an electron's spin and its linear motion in a material.

"Spin-orbit coupling is often a bad thing," said JQI's Ian Spielman, senior author of the paper. "Researchers make ‘spintronic' devices out of gallium arsenide, and if you've prepared a spin in some desired orientation, the last thing you'd want it to do is to flip to some other spin when it's moving."

"But from the point of view of fundamental physics, spin-orbit coupling is really interesting," he said. "It's what drives these new kinds of materials called ‘topological insulators.'"

One of the hottest topics in physics right now, topological insulators are special materials in which location is everything: the ability of electrons to flow depends on where they are located within the material. Most regions of such a material are insulating, and electric current does not flow freely. But in a flat, two-dimensional topological insulator, current can flow freely along the edge in one direction for one type of spin, and the opposite direction for the opposite kind of spin. In 3-D topological insulators, electrons would flow freely on the surface but be inhibited inside the material. While researchers have been making higher and higher quality versions of this special class of material in solids, spin-orbit coupling in trapped ultracold gases of atoms could help realize topological insulators in their purest, most pristine form, as gases are free of impurity atoms and the other complexities of solid materials.

Usually, atoms do not exhibit the same kind of spin-orbit coupling as electrons exhibit in gallium-arsenide crystals. While each individual atom has its own spin-orbit coupling going on between its internal components (electrons and nucleus), the atom's overall motion generally is not affected by its internal energy state.

But the researchers were able to change that. In their experiment, researchers trapped and cooled a gas of about 200,000 rubidium-87 atoms down to 100 nanokelvins, 3 billion times colder than room temperature. The researchers selected a pair of energy states, analogous to the "spin-up" and "spin-down" states in an electron, from the available atomic energy levels. An atom could occupy either of these "pseudospin" states. Then researchers shined a pair of lasers on the atoms so as to change the relationship between the atom's energy and its momentum (its mass times velocity), and therefore its motion. This created spin-orbit coupling in the atom: the moving atom flipped between its two "spin" states at a rate that depended upon its velocity.

"This demonstrates that the idea of using laser light to create spin-orbit coupling in atoms works. This is all we expected to see," Spielman said. "But something else really neat happened."

They turned up the intensity of their lasers, and atoms of one spin state began to repel the atoms in the other spin state, causing them to separate.

"We changed fundamentally how these atoms interacted with one another," Spielman said. "We hadn't anticipated that and got lucky."

The rubidium atoms in the researchers' experiment were bosons, sociable particles that can all crowd into the same space even if they possess identical values in their properties including spin. But Spielman's calculations show that they could also create this same effect in ultracold gases of fermions. Fermions, the more antisocial type of atoms, cannot occupy the same space when they are in an identical state. And compared to other methods for creating new interactions between fermions, the spin states would be easier to control and longer lived.

A spin-orbit-coupled Fermi gas could interact with itself because the lasers effectively split each atom into two distinct components, each with its own spin state, and two such atoms with different velocities could then interact and pair up with one other. This kind of pairing opens up possibilities, Spielman said, for studying novel forms of superconductivity, particularly "p-wave" superconductivity, in which two paired atoms have a quantum-mechanical phase that depends on their relative orientation. Such p-wave superconductors may enable a form of quantum computing known as topological quantum computation.

* Y.-J. Lin, K. Jiménez-García and I.B. Spielman. Spin-orbit-coupled Bose-Einstein condensates. Nature. Posted online March 2, 2011.

Sign Up for NIST E-mail alerts:

####

About NIST

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the U.S. Commerce Department.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Ben Stein

301-975-3067

Copyright © NIST

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Physics

![]() Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

![]() Magnetism in new exotic material opens the way for robust quantum computers June 4th, 2025

Magnetism in new exotic material opens the way for robust quantum computers June 4th, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Spintronics

![]() Quantum materials: Electron spin measured for the first time June 9th, 2023

Quantum materials: Electron spin measured for the first time June 9th, 2023

Quantum Computing

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

![]() Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Quantum nanoscience

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||