Home > Press > Water Could Hold Answer to Graphene Nanoelectronics

|

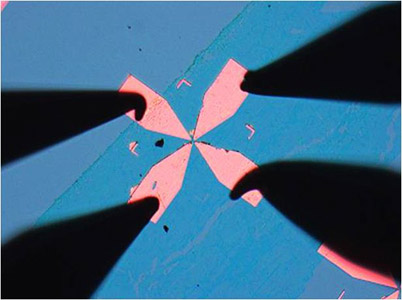

| Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute developed a new method for using water to tune the band gap of the nanomaterial graphene, opening the door to new graphene-based transistors and nanoelectronics. In this optical micrograph image, a graphene film on a silicon dioxide substrate is being electrically tested using a four-point probe. |

Abstract:

Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Use Water to Open, Tune Graphene's Band Gap

Water Could Hold Answer to Graphene Nanoelectronics

Troy, NY | Posted on October 26th, 2010Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute developed a new method for using water to tune the band gap of the nanomaterial graphene, opening the door to new graphene-based transistors and nanoelectronics.

By exposing a graphene film to humidity, Rensselaer Professor Nikhil Koratkar and his research team were able to create a band gap in graphene — a critical prerequisite to creating graphene transistors. At the heart of modern electronics, transistors are devices that can be switched "on" or "off" to alter an electrical signal. Computer microprocessors are comprised of millions of transistors made from the semiconducting material silicon, for which the industry is actively seeking a successor.

Graphene, an atom-thick sheet of carbon atoms arranged like a nanoscale chain-link fence, has no band gap. Koratkar's team demonstrated how to open a band gap in graphene based on the amount of water they adsorbed to one side of the material, precisely tuning the band gap to any value from 0 to 0.2 electron volts. This effect was fully reversible and the band gap reduced back to zero under vacuum. The technique does not involve any complicated engineering or modification of the graphene, but requires an enclosure where humidity can be precisely controlled.

"Graphene is prized for its unique and attractive mechanical properties. But if you were to build a transistor using graphene, it simply wouldn't work as graphene acts like a semi-metal and has zero band gap," said Koratkar, a professor in the Department of Mechanical, Aerospace, and Nuclear Engineering at Rensselaer. "In this study, we demonstrated a relatively easy method for giving graphene a band gap. This could open the door to using graphene for a new generation of transistors, diodes, nanoelectronics, nanophotonics, and other applications."

Results of the study were detailed in the paper "Tunable Band gap in Graphene by the Controlled Adsorbtion of Water Molecules," published this week by the journal Small. See the full paper at: dx.doi.org/10.1002/smll.201001384

In its natural state, graphene has a peculiar structure but no band gap. It behaves as a metal and is known as a good conductor. This is compared to rubber or most plastics, which are insulators and do not conduct electricity. Insulators have a large band gap — an energy gap between the valence and conduction bands — which prevents electrons from conducting freely in the material.

Between the two are semiconductors, which can function as both a conductor and an insulator. Semiconductors have a narrow band gap, and application of an electric field can provoke electrons to jump across the gap. The ability to quickly switch between the two states — "on" and "off" — is why semiconductors are so valuable in microelectronics.

"At the heart of any semiconductor device is a material with a band gap," Koratkar said. "If you look at the chips and microprocessors in today's cell phones, mobile devices, and computers, each contains a multitude of transistors made from semiconductors with band gaps. Graphene is a zero band gap material, which limits its utility. So it is critical to develop methods to induce a band gap in graphene to make it a relevant semiconducting material."

The symmetry of graphene's lattice structure has been identified as a reason for the material's lack of band gap. Koratkar explored the idea of breaking this symmetry by binding molecules to only one side of the graphene. To do this, he fabricated graphene on a surface of silicon and silicon dioxide, and then exposed the graphene to an environmental chamber with controlled humidity. In the chamber, water molecules adsorbed to the exposed side of the graphene, but not on the side facing the silicon dioxide. With the symmetry broken, the band gap of graphene did, indeed, open up, Koratkar said. Also contributing to the effect is the moisture interacting with defects in the silicon dioxide substrate.

"Others have shown how to create a band gap in graphene by adsorbing different gasses to its surface, but this is the first time it has been done with water," he said. "The advantage of water adsorption, compared to gasses, is that it is inexpensive, nontoxic, and much easier to control in a chip application. For example, with advances in micro-packaging technologies it is relatively straightforward to construct a small enclosure around certain parts or the entirety of a computer chip in which it would be quite easy to control the level of humidity."

Based on the humidity level in the enclosure, chip makers could reversibly tune the band gap of graphene to any value from 0 to 0.2 electron volts, Korarkar said.

Along with Koratkar, authors on the paper are Theodorian Borca-Tasciuc, associate professor in the Department of Mechanical, Aerospace, and Nuclear Engineering at Rensselaer; Rensselaer mechanical engineering graduate student Fazel Yavari, who was first author on the paper; Rensselaer Focus Center New York Postdoctoral Research Associate Churamani Gaire; and undergraduate student Christo Kritzinger. Co-authors from Rice University are Professor Pulickel M. Ajayan; Postdoctoral Research Fellow Li Song; and graduate student Hemtej Gulapalli.

This study was supported by the Advanced Energy Consortium (AEC), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Nanoelectronics Research Initiative, and the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Basic Energy Sciences (BES).

For more information on Koratkar's graphene research at Rensselaer, visit:

Graphene Outperforms Carbon Nanotubes for Creating Stronger, More Crack-Resistant Materials news.rpi.edu/update.do?artcenterkey=2715

Rensselaer Researchers Secure $1 Million Grant To Develop Oil Exploration Game-Changer news.rpi.edu/update.do?artcenterkey=2700

Helping Hydrogen: Student Inventor Tackles Challenge of Hydrogen Storage

news.rpi.edu/update.do?artcenterkey=2690

Koratkar also was recently appointed as the editor of the journal Carbon: www.elsevier.com/wps/find/P10.cws_home/carbon_neweditors

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Michael Mullaney

Phone: (518) 276-6161

Copyright © Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

![]() "Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

"Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

![]() Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

Academic/Education

![]() Rice University launches Rice Synthetic Biology Institute to improve lives January 12th, 2024

Rice University launches Rice Synthetic Biology Institute to improve lives January 12th, 2024

![]() Multi-institution, $4.6 million NSF grant to fund nanotechnology training September 9th, 2022

Multi-institution, $4.6 million NSF grant to fund nanotechnology training September 9th, 2022

Chip Technology

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

![]() Programmable electron-induced color router array May 14th, 2025

Programmable electron-induced color router array May 14th, 2025

Nanotubes/Buckyballs/Fullerenes/Nanorods/Nanostrings

![]() Enhancing power factor of p- and n-type single-walled carbon nanotubes April 25th, 2025

Enhancing power factor of p- and n-type single-walled carbon nanotubes April 25th, 2025

![]() Chainmail-like material could be the future of armor: First 2D mechanically interlocked polymer exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength January 17th, 2025

Chainmail-like material could be the future of armor: First 2D mechanically interlocked polymer exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength January 17th, 2025

![]() Innovative biomimetic superhydrophobic coating combines repair and buffering properties for superior anti-erosion December 13th, 2024

Innovative biomimetic superhydrophobic coating combines repair and buffering properties for superior anti-erosion December 13th, 2024

Nanoelectronics

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() Interdisciplinary: Rice team tackles the future of semiconductors Multiferroics could be the key to ultralow-energy computing October 6th, 2023

Interdisciplinary: Rice team tackles the future of semiconductors Multiferroics could be the key to ultralow-energy computing October 6th, 2023

![]() Key element for a scalable quantum computer: Physicists from Forschungszentrum Jülich and RWTH Aachen University demonstrate electron transport on a quantum chip September 23rd, 2022

Key element for a scalable quantum computer: Physicists from Forschungszentrum Jülich and RWTH Aachen University demonstrate electron transport on a quantum chip September 23rd, 2022

![]() Reduced power consumption in semiconductor devices September 23rd, 2022

Reduced power consumption in semiconductor devices September 23rd, 2022

Announcements

![]() Rice membrane extracts lithium from brines with greater speed, less waste October 3rd, 2025

Rice membrane extracts lithium from brines with greater speed, less waste October 3rd, 2025

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

![]() "Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

"Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||