Home > Press > Scientists Watch Membrane Fission in Real Time, Identifying a Cellular Fission Machine

|

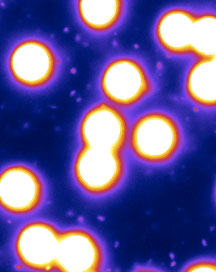

| The scientists used a new technique they developed to visualize the formation of "daughter vesicles" from a "parent" cell's outer membrane. |

Abstract:

By Renee Twombly

Researchers at The Scripps Research Institute have solved one of biology's neatest little tricks: they have discovered how a cell's outer membrane pinches a little pouch from itself to bring molecules outside the cell inside—without making holes that leak fluid from either side of the membrane.

Scientists Watch Membrane Fission in Real Time, Identifying a Cellular Fission Machine

La Jolla, CA | Posted on December 15th, 2008In the December 26 issue of the journal Cell, the scientists describe creating a system in which they can watch, in real time under a light microscope, cell membranes bud and then pinch off smaller sack-like "vesicles."

This process is only possible, Scripps Research scientists say, because a single molecule, dynamin, forms a short "collar" of proteins around a bit of the membrane that has emerged from the "parent" membrane, and then squeezes it tight, cleanly separating the new "daughter" vesicle.

"Doing this without leaking is quite a feat," says Sandra Schmid, chair of the Scripps Research Department of Cell Biology, who authored the paper with Thomas Pucadyil, a postdoctoral researcher in her lab. "A cell's outside environment is very nasty, and if any of that toxic fluid got into the cell, it would kill it."

The findings contradict the prevailing notion of how these vesicles are tied off from the membrane, and also suggest that this elegant little action may be ubiquitous throughout the cell, which must form millions of vesicles to move molecules between membrane organelles within the cell.

In this process, called endocytosis, cells take up materials (including hormones, nutrients, antibodies, and fats such as cholesterol) from the bloodstream by engulfing them in inward folds of the cell membrane that then close up, pinch off, and move into the cell as the cargo-laden vesicles.

This study focused on the proteins that actually pinch off the vesicle. The prevailing theory has been that a molecule called dynamin is responsible for the process, but that it does it by first forming a very long chain spiral, shaped like a Slinky® Toy, around the neck of the vesicle. Once in place, it was hypothesized that the dynamin spiral tightened. This constriction requires the presence of GTP, a small molecule that provides the fuel fordynamin, a GTPase, to perform the action. Many researchers believed that the constriction helped to pinched off the vesicle but that dynamin could not function alone.

That's not what Schmid and Pucadyil found. To see exactly what happens, Pucadyil, a biophysicist, invented a new membrane template to study the process as it happens. He used tiny glass beads—200 of them could fit on to the head of a pin—and formed membranes around each one of them. "The beauty of this is that we can see these beads using a normal light microscope," Schmid says. Each bead contains a loosely fitting bi-layer membrane, just like a cell would have.

The scientists then added dynamin alone and watched what occurred. The beads formed long hairy spirals, just as the prevailing hypothesis would predict, but surprisingly no fission (the pinching off of daughter vesicles) took place even when they added GTP later.

The researchers then tried a slightly different condition. They added GTP first and then dynamin to the membrane beads. In this case, "we didn't see any hairy structures at all—just little vesicles popping off the beads," Schmid says. "It was an exciting moment when Thomas first saw the small daughter vesicles emerge from the mother 'ship' and dance around it."

Close analysis demonstrated that only in the constant presence of GTP does dynamin form short collars at the neck of the vesicles that then tighten to break them free of the membrane.

An accompanying study in Cell led by Vadim Frolov and Josh Zimmerberg, which includes Schmid as a co-author, extends these findings into a "unified theory as to how intracellular vesicle formation works," she says. "Dynamin is often involved in forming the vesicles that help move molecules and chemicals inside cells, so this work provides a model as to how these other processes occur."

Schmid says the new technology developed at Scripps Research, which they dub SUPER (fluid supported bi-layers with excess membrane reservoir) templates can now easily be used to test these theories. "It is easy, done in real time, and can be seen through a simple microscope," she says.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and a fellowship from The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

For more information, see www.cell.com/abstract/S0092-8674(08)01495-5.

####

About The Scripps Research Institute

The Scripps Research Institute, one of the country's largest, private, non-profit research organizations, has always stood at the forefront of basic biomedical science, a vital segment of medical research that seeks to comprehend the most fundamental processes of life. In just three decades the Institute has established a lengthy track record of major contributions to the betterment of health and the human condition.

The Institute has become internationally recognized for its basic research into immunology, molecular and cellular biology, chemistry, neurosciences, autoimmune diseases, cardiovascular diseases, virology and synthetic vaccine development. Particularly significant is the Institute's study of the basic structure and design of biological molecules; in this arena TSRI is among a handful of the world's leading centers.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Mika Ono

(858) 784-8133

Copyright © The Scripps Research Institute

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Imaging

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||