Home > Press > The Greenest Diet: Bacteria Switch to Eating Carbon Dioxide: Such bacteria may, in the future, contribute to new, carbon-efficient technologies

|

Abstract:

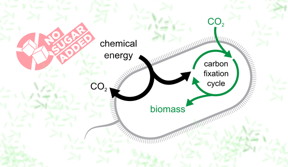

Bacteria in the lab of Prof. Ron Milo of the Weizmann Institute of Science have not just sworn off sugar – they have stopped eating all of their normal solid food, existing instead on carbon dioxide (CO2) from their environment. That is, they were able to build all of their biomass from air. This feat, which involved nearly a decade of rational design, genetic engineering and a sped-up version of evolution in the lab, was reported this week in Cell. The findings point to means of developing, in the future, carbon-neutral fuels.

The Greenest Diet: Bacteria Switch to Eating Carbon Dioxide: Such bacteria may, in the future, contribute to new, carbon-efficient technologies

Rehovot, Israel | Posted on November 27th, 2019The study began by identifying crucial genes for the process of carbon fixation – the way plants take carbon from CO2 for the purpose of turning it into such biological molecules as protein, DNA, etc. The research team added and rewired the needed genes. They found that many of the “parts” for the machinery that were already present in the bacterial genome could be used as is. They also inserted a gene that allowed the bacteria to get energy from a readily available substance called formate that can be produced directly from electricity and air and which is apt to “give up” electrons to the bacteria.

Just giving the bacteria the “means of production” was not enough, it turned out, for them to make the switch. There was still a need for another trick to get the bacteria to use this machinery properly, and this involved a delicate balancing act. Together with Roee Ben-Nissan, Yinon Bar-On and other members of Milo’s team in the Institute’s Plant and Environmental Sciences Department, Gleizer used lab evolution, as the technique is known; in essence, the bacteria were gradually weaned off the sugar they were used to eating. At each stage, cultured bacteria were given just enough sugar to keep them from complete starvation, as well as plenty of CO2 and formate. As some “learned” to develop a taste for CO2 (giving them an evolutionary edge over those that stuck to sugar), their descendants were given less and less sugar until after about a year of adapting to the new diet some of them eventually made the complete switch, living and multiplying in an environment that served up pure CO2.

To check whether the bacteria were not somehow “snacking” on other nutrients, some of the evolved E. coli were fed CO2 containing a heavy isotope – C13. Then the bacterial body parts were weighed, and the weight they had gained checked against the mass that would be added from eating the heavier version of carbon. The analysis showed the carbon atoms in the body of the bacteria were all extracted directly from CO2 alone.

The research team then set out to characterize the newly-evolved bacteria. What changes were essential to adapting to this new diet? While some of the genetic changes they identified may have been tied to surviving hunger, others appeared to regulate the synchronization of the steps of making building blocks through accumulation from CO2. “The cell needs to balance between toxic congestion and bankruptcy,” says Bar-On. Yet other changes the team noted had to do with transcription – regulating how existing genes are turned on and off. “Further research will hopefully uncover exactly how these genes have adjusted their activities,” says Ben-Nissan.

The researchers believe that the bacteria’s new “health kick” could ultimately be healthy for the planet. Milo points out that today, biotech companies use cell cultures to produce commodity chemicals. Such cells – yeast or bacteria – could be induced to live on a diet of CO2 and renewable electricity, and thus be weaned from the large amounts of corn syrup they live on today. Bacteria could be further adapted so that rather than taking their energy from a substance such as formate, they might be able to get it straight up -- say electrons from a solar collector – and then store that energy for later use as fuel in the form of carbon fixed in their cells. Such fuel would be carbon-neutral if the source of its carbon was atmospheric CO2.

“Our lab was the first to pursue the idea of changing the diet of a normal heterotroph (one that eats organic substances) to convert it to autotrophism (‘living on air’),” says Milo. “It sounded impossible at first, but it has taught us numerous lessons along the way, and in the end we showed it indeed can be done. Our findings are a significant milestone toward our goal of efficient, green scientific applications.”

Prof. Ron Milo is the Head of the Mary and Tom Beck - Canadian Center for Alternative Energy Research. His research is supported by the Zuckerman STEM Leadership Program; the Larson Charitable Foundation New Scientist Fund; the Ullmann Family Foundation; Dana and Yossie Hollander; and the European Research Council. Prof. Milo is the incumbent of the Charles and Louise Gartner Professorial Chair.

####

About Weizmann Institute of Science

The Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, is one of the world's top-ranking multidisciplinary research institutions. Noted for its wide-ranging exploration of the natural and exact sciences, the Institute is home to scientists, students, technicians and supporting staff. Institute research efforts include the search for new ways of fighting disease and hunger, examining leading questions in mathematics and computer science, probing the physics of matter and the universe, creating novel materials and developing new strategies for protecting the environment.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Yael Edelman

Department of Media Relations

Weizmann Institute of Science

P.O. Box 26, Rehovot 76100

Israel

Tel: 972 8 934 3852

Copyright © Weizmann Institute of Science

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Environment

![]() Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

![]() Onion-like nanoparticles found in aircraft exhaust May 14th, 2025

Onion-like nanoparticles found in aircraft exhaust May 14th, 2025

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Grants/Sponsored Research/Awards/Scholarships/Gifts/Contests/Honors/Records

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

![]() New discovery aims to improve the design of microelectronic devices September 13th, 2024

New discovery aims to improve the design of microelectronic devices September 13th, 2024

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||