Home > Press > Electric skyrmions charge ahead for next-generation data storage: Berkeley Lab-led research team makes a chiral skyrmion crystal with electric properties; puts new spin on future information storage applications

|

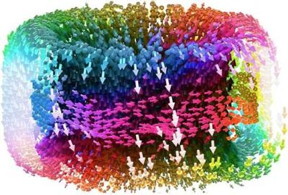

| Simulation of a single polar skyrmion. Red arrows signify that this is a left-handed skyrmion. The other arrows represent the angular distribution of the dipoles. CREDIT Xiaoxing Cheng, Pennsylvania State University; C.T. Nelson, Oak Ridge National Laboratory; and Ramamoorthy Ramesh, Berkeley Lab |

Abstract:

When you toss a ball, what hand do you use? Left-handed people naturally throw with their left hand, and right-handed people with their right. This natural preference for one side versus the other is called handedness, and can be seen almost everywhere - from a glucose molecule whose atomic structure leans left, to a dog who shakes "hands" only with her right.

Electric skyrmions charge ahead for next-generation data storage: Berkeley Lab-led research team makes a chiral skyrmion crystal with electric properties; puts new spin on future information storage applications

Berkeley, CA | Posted on April 18th, 2019Handedness can be exhibited in chirality - where two objects, like a pair of gloves, can be mirror images of each other but cannot be superimposed on one another. Now a team of researchers led by Berkeley Lab has observed chirality for the first time in polar skyrmions - quasiparticles akin to tiny magnetic swirls - in a material with reversible electrical properties. The combination of polar skyrmions and these electrical properties could one day lead to applications such as more powerful data storage devices that continue to hold information - even after a device has been powered off. Their findings were reported this week in the journal Nature.

"What we discovered is just mind-boggling," said Ramamoorthy Ramesh, who holds appointments as a faculty senior scientist in Berkeley Lab's Materials Sciences Division and as the Purnendu Chatterjee Endowed Chair in Energy Technologies in Materials Science and Engineering and Physics at UC Berkeley. "We hadn't planned on making skyrmions. So for us to end up making a chiral skyrmion is exciting."

When the team of researchers - co-led by Ramesh and Lane Martin, a staff scientist in Berkeley Lab's Materials Sciences Division and a professor in Materials Science and Engineering at UC Berkeley - began this study in 2016, they had set out to find ways to control how heat moves through materials. So they fabricated a special crystal structure called a superlattice from alternating layers of lead titanate (an electrically polar material, whereby one end is positively charged and the opposite end is negatively charged) and strontium titanate (an insulator, or a material that doesn't conduct electric current).

But once they took STEM (scanning transmission electron microscopy) measurements of the lead titanate/strontium titanate superlattice at the Molecular Foundry, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility at Berkeley Lab that specializes in nanoscale science, they saw something strange that had nothing to do with heat: Bubble-like formations had cropped up all across the device.

Bubbles, bubbles everywhere

So what were these "bubbles," and how did they get there?

Those bubbles, it turns out, were polar skyrmions - or textures made up of opposite electric charges known as dipoles. Researchers had always assumed that skyrmions would only appear in magnetic materials, where special interactions between magnetic spins of charged electrons stabilize the twisting chiral patterns of skyrmions. So when the Berkeley Lab-led team of researchers discovered skyrmions in an electric material, they were astounded.

Through the researchers' collaboration with theorists Javier Junquera of the University of Cantabria in Spain, and Jorge Íńiguez of the Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology, they discovered that these textures had a unique feature called a "Bloch component" that determined the direction of its spin, which Ramesh compares to the fastening of a belt - where if you're left-handed, the belt goes from left to right. "And it turned out that this Bloch component - the skyrmion's equatorial belt, so to speak - is the key to its chirality or handedness," he said.

While using sophisticated STEM at Berkeley Lab's Molecular Foundry and at the Cornell Center for Materials Research, where David Muller of Cornell University took atomic snapshots of skyrmions' chirality at room temperature in real time, the researchers discovered that the forces placed on the polar lead titanate layer by the nonpolar strontium titanate layer generated the polar skyrmion "bubbles" in the lead titanate.

"Materials are like people," said Ramesh. "When people get stressed, they respond in unpredictable ways. And that's what materials do too: In this case, by surrounding lead titanate by strontium titanate, lead titanate starts to go crazy - and one way that it goes crazy is to create polar textures like skyrmions."

Shining a light on crystal chirality

To confirm their observations, senior staff scientist Elke Arenholz and staff scientist Padraic Shafer at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source (ALS), along with Margaret McCarter, a physics Ph.D. student from the Ramesh Lab at UC Berkeley, probed the chirality by using a spectroscopic technique known as RSXD-CD (resonant soft X-ray diffraction circular dichroism), one of the highly optimized tools available to the scientific community at the ALS, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility that specializes in lower energy, "soft" X-ray light for studying the properties of materials.

Light waves can be "circularly polarized" to also have handedness, so the researchers theorized that if polar skyrmions have handedness, a left-handed skyrmion, for example, should interact more strongly with left-handed, circularly polarized light - an effect known as circular dichroism.

When McCarter and Shafer tested the samples at the ALS, they successfully uncovered another piece to the chiral skyrmion puzzle - they found that incoming circularly polarized X-rays, like a screw whose threads rotate either clockwise or counterclockwise, interact with skyrmions whose dipoles rotate in the same direction, even at room temperature. In other words, they found evidence of circular dichroism - where there is only a strong interaction between X-rays and polar skyrmions with the same handedness.

"The theoretical simulations and microscopy both revealed the presence of a Bloch component, but to confirm the chiral nature of these skyrmions, the last piece of the puzzle was really the circular dichroism measurements," McCarter said. "It is amazing to observe this effect in materials that typically don't have handedness. We are excited to explore the implications of this chirality in a ferroelectric and how it can be controlled in a way that could be useful for storing data."

Now that the researchers have made a single electric skyrmion and confirmed its chirality, they plan to make an array of dozens of electric skyrmions - each one with a diameter of just 8 nm (for comparison, the Ebola virus is about 50 nm wide) - with the same handedness. "In terms of applications, this is exciting because now we have chirality - switching a skyrmion on or off, or between left-handed and right-handed - on top of still being able to use the charge for storing data," Ramesh said.

The researchers next plan to study the effects of applying an electric field on the skyrmions. "Now that we know that skyrmions are chiral, we want to see if we can electrically manipulate them. If I apply an electric field, can I turn each one like a turnstile? Can I move each one, one at a time, like a checker on a checkerboard? If we can somehow move them, write them, and erase them for data storage, then that would be an amazing new technology," Ramesh said.

###

Also contributing to the study were researchers from Pennsylvania State University, Cornell University, and Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The work was supported by the DOE Office of Science with additional funding provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation's EPiQS Initiative, the National Science Foundation, the Luxembourg National Research Fund, and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

####

About Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab's facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Theresa Duque

510-495-2418

Copyright © Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

Skyrmions

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Memory Technology

![]() Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||