Home > Press > Perking up and crimping the 'bristles' of polyelectrolyte brushes

|

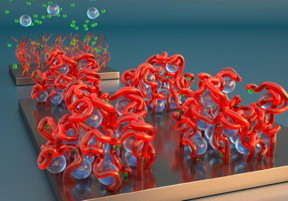

| Polyelectrolyte brushes illustration: In the foreground, powerful ions in solution, shown as spheres, cause the brush's bristles to collapse like sticky spaghetti. In the background, gentler ions in solution cause the bristles to stand back straight. CREDIT Peter Allen University of California Santa Barbara for this study / press handout |

Abstract:

If the bristles of a brush abruptly collapsed into wads of noodles, the brush would, of course, become useless. When it's a micron-scale brush called a "polyelectrolyte brush," that collapse can put a promising experimental drug or lubricant out of commission.

Perking up and crimping the 'bristles' of polyelectrolyte brushes

Atlanta, GA | Posted on December 13th, 2017But now a new study reveals, in fine detail, things that make these special bristles collapse -- and also recover. The research increases understanding of these chemical brushes that have many potential uses.

What are polyelectrolyte brushes?

Polyelectrolyte brushes look a bit like soft bushes, such as shoeshine brushes, but they are on the scale of large molecules and the "bristles" are made of polymer chains. Polyelectrolyte brushes have a backing, or substrate, and the polymer chains tethered to the backing like soft bristles have chemical properties that make the brush potentially interesting for many practical uses.

But polymers are stringy and tend to get tangled or clumped, and keeping them straightened out, like soft bristles, is vital to the function of these micron brushes. Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology, the University of Chicago, and the Argonne National Laboratory devised experiments that caused polyelectrolyte brush bristles to collapse and then recover from the collapse.

They imaged the processes in detail with highly sensitive atomic force microscopy, and they constructed simulations that closely matched their observations. Principal investigator Blair Brettmann from Georgia Tech and the study's first authors Jing Yu and Nicholas Jackson from the University of Chicago published their results on December 8, 2017, in the journal Science Advances.

Their research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation, and the Argonne National Laboratory.

From faux DNA to lubricants

The potential future payoff for the researchers' work spans industrial materials to medicine.

For example, polyelectrolyte brushes make for surfaces that have their own built-in lubrication. "If you attach the brushes to opposing surfaces, and the bristles rub against each other, then they have really low friction and excellent lubrication properties," said Blair Brettmann, who led the study and recently joined Georgia Tech from the University of Chicago.

Polyelectrolyte brushes could also one day find medical applications. Their bristles have been shown to simulate DNA and encode simple proteins. Other brushes could be engineered to repel bacteria from surfaces. Some polyelectrolyte brushes already exist in the body on the surface of some cells.

Polyelectrolyte brushes can do so many different things because they can be engineered in so many variations.

"When you build the brushes, you have a lot of control," said Brettmann, who is an assistant professor in Georgia Tech's School of Materials Science and Engineering. "You can control on the nanoscale how far apart the polymer chains (the bristles) are spaced on the substrate and how long they are."

They're intricate and sensitive

For all their great potential, polyelectrolyte brushes are also complex and sensitive, and a lot of research is needed to understand how to optimize them.

The polymer chains have positive and negative ionic, or electrolytic, charges alternating along their lengths, thus the name "polyelectrolyte." Chemists can string the polymers together using various chemical building blocks, or monomers, and design nuanced charge patterns up and down the chain.

There's more complexity: Backing and bristles are not all that make up polyelectrolyte brushes. They're bathed in solutions containing gentle electrolytes, which create a balanced ionic pull from all sides that props the bristles up instead of letting them collapse or entangle.

"Often these mixtures have a bunch of other stuff in them, so the complexity of this makes it really hard to understand fundamentally," Brettmann said, "and thus hard to be able to predict behavior in real applications."

Invading impurities

When other chemicals enter into these well-balanced systems that make up polyelectrolyte brushes, they can make the bristles collapse. For example, the addition of very powerful electrolytes can act like a flock of wrecking balls.

In their experiment, Brettmann and her colleagues used a powerful ionic compound built around yttrium, a rare earth metal with a strong charge. (The ion was trivalent, or had a valence of 3.) The ionic forces from just a low dose of the yttrium electrolyte made the polymer bristles curl up like clumps of sticky spaghetti.

Then the researchers increased the concentration of the gentler ions, which restored support, propping the bristles back up. Atomic force microscope imaging revealed highly regular patterns of collapse and re-extension.

These patterns were reflected well in the simulations; the reliability of the effects of the ions on collapse and recovery even more so. The ability to build such an accurate simulation reflects the strong consistency of the chemistry, which is good news for potential future research and practical applications.

Useless becomes useful

For all the dysfunction that bristle collapses can cause, the ability to collapse them on purpose can be useful. "If you could collapse and reactivate the bristles systematically, you could adjust the degree of lubrication, for example, or turn lubrication on and off," Brettmann said.

The brushes also could regulate chemical reactions involving micro- and nanoparticles by extending and collapsing the bristles.

"Coatings and films are often made by carefully combining engineered particles, and you can use these brushes to keep these particles suspended and separate until you're ready to let them meet, bond, and form the product," Brettmann said.

When the polyelectrolyte brush's bristles are extended, they act as a barrier to hold the particles apart. Collapse the bristles out of the way on purpose, and the particles can come together.

It's a nasty world

The experiments were performed with very clean, robust, and uniform compounds unlike the jumble of chemicals that can exist in natural or even industrial systems.

"The bristles we used were polystyrene sulfonate, which is a very strong polyelectrolyte, not sensitive to pH or much else," Brettmann said. "Biopolymers like polysaccharides, for example, are a lot more sensitive."

Like many experiments, this one was a departure from real-world conditions. But by creating a foundation for understanding how these systems work, Brettmann wants eventually to be able to move on to sensitive scenarios to realize more of polyelectrolyte brushes' practical potential.

###

The study was co-authored by Xin Xu, Marina Ruths, Juan de Pablo and Matthew Tirrell. The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Program in Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, the National Science Foundation's Division of Civil, Mechanical, and Manufacturing Innovation (grants 1562876 and 1161475), the Argonne National Laboratory Maria Goeppert Mayer Named AQ41Fellowship. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of those sponsors.

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Ben Brumfield

404-660-1408

Copyright © Georgia Institute of Technology

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Imaging

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Friction/ Tribology

![]() Movable microplatform floats on a sea of droplets: New technique offers precise, durable control over tiny mirrors or stages December 19th, 2016

Movable microplatform floats on a sea of droplets: New technique offers precise, durable control over tiny mirrors or stages December 19th, 2016

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Nanomedicine

![]() New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Tools

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Nanobiotechnology

![]() New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Ben-Gurion University of the Negev researchers several steps closer to harnessing patient's own T-cells to fight off cancer June 6th, 2025

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev researchers several steps closer to harnessing patient's own T-cells to fight off cancer June 6th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||