Home > Press > Titan shines light on high-temperature superconductor pathway: Simulation demonstrates how superconductivity arises in cuprates' pseudogap phase

|

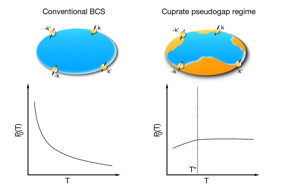

| In conventional, low-temperature superconductivity (left), so-called Cooper pairing arises from the presence of an electron Fermi sea. In the pseudogap regime of the cuprate superconductors (right), parts of the Fermi sea are "dried out" and the charge-carrier pairing arises through an increase in the strength of the spin-fluctuation pairing interaction as the temperature is lowered. CREDIT: ORNL |

Abstract:

When physicists Georg Bednorz and K. Alex Muller discovered the first high-temperature superconductors in 1986, it didn't take much imagination to envision the potential technological benefits of harnessing such materials.

Titan shines light on high-temperature superconductor pathway: Simulation demonstrates how superconductivity arises in cuprates' pseudogap phase

Oak Ridge, TN | Posted on June 22nd, 2016High-temperature superconductors are materials that can transport electricity with perfect efficiency at or near liquid nitrogen temperatures (-196 degrees Celsius). Though their operating temperature may seem cold, they're a summer afternoon in the tropics compared to their previously known brethren, so-called conventional superconductors, which operate at temperatures near absolute zero (-273.15 degrees Celsius).

Hyperefficient electricity transmission could revolutionize power grids and electronic devices, enabling a wide range of new technologies. That future energy economy, however, is predicated on advancements in the understanding of how high-temperature superconductors work at the microscopic level.

Since this discovery, scientists have been working to develop a theory that explains the essential physics of high-temperature superconductors like copper oxides, called cuprates. A sound theory would not only explain why a material superconducts at high temperatures but also suggest other materials that could be created to superconduct at temperatures closer to room temperature.

At the heart of this mystery is the behavior of high-temperature superconductors' electrons in their normal state (i.e., before they become superconducting). A team led by Thomas Maier of the US Department of Energy's (DOE's) Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) used the Titan supercomputer at ORNL to simulate cuprates on the path to superconductivity. Titan, America's fastest supercomputer for open science, is the flagship machine of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility (OLCF), a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

Maier's team focused on a pivotal juncture on the cuprates' path called the pseudogap phase, an in-between phase before superconductivity in which cuprates exhibit both insulating and conducting properties. Under these conditions, the conventional pathway to superconductivity is blocked. Maier's team, however, identified a possible alternative route mediated by the magnetic push-and-pull of cuprates' electrons.

Simulating a 16-atom cluster, the team measured a strengthening fluctuation of electronic antiferromagnetism, a specific magnetic ordering in which the spins of neighboring electrons point in opposite directions (up and down), as the system cooled. The findings add context to scientists' understanding of the pseudogap and how superconductivity emerges from the phase.

Bridging the (Pseudo)gap

At extremely cold temperatures, electrons in certain materials do unexpected things. They pair up, overcoming their natural repulsion toward one another, and gain the ability to flow freely between atoms without resistance, like a school of fish in synchronized motion.

In conventional low-temperature superconductors such as mercury, aluminum, and lead, the explanation for this phenomenon--called Cooper pairing--is well understood. In 1957, John Bardeen, Leon Cooper, and John Robert Schrieffer proved that Cooper pairs arise from the interaction between electrons and a material's vibrating crystal lattice (phonons). This theory, however, doesn't seem to apply to cuprates and other high-temperature superconductors, which are more complex in their composition and electronic structure.

Cuprates consist of two-dimensional layers of copper and oxygen. The layers are stacked on top of each other with additional insulating elements in between. To set the stage for superconductivity, trace elements are substituted between the copper and oxygen layers to draw out electrons and create "holes," impurities in the electrons' magnetic ordering that act as charge carriers.

At sufficiently low temperatures, this process, called hole doping, results in the emergence of a pseudogap, a transition marked by electronic stops and starts, like a traffic jam struggling to pick up speed.

"In a conventional superconductor, the probability of electrons forming Cooper pairs grows as the temperatures decreases," Maier said. "In cuprates, the pseudogap's insulating properties disrupt that mechanism. That begs the question, how can pairing arise?"

According to the team's simulations, the antiferromagnetic fluctuations of electrons' own spin is enough to form the glue.

"These spin fluctuations become much stronger as the material cools down," Maier said. "The interaction is actually very similar to the lattice vibrations, or phonons, in conventional superconductors--except in high-temperature superconductors, the normal state of electrons is not well-defined and the phonon interaction does not become stronger with cooling."

Maier's team approached the problem with an application called DCA++, calculating a cluster of atoms using a two-dimensional Hubbard model--a mathematical description of how electrons behave in solid materials. DCA++, which stands for "dynamical cluster approximation," relies on a quantum Monte Carlo technique involving repeated random sampling to obtain its results.

"This model is very simple--it's a very short equation--and yet it's very hard to solve," Maier said. "The problem is complex because it scales exponentially with the number of electrons in your system and you need a large number of electrons to describe thermodynamic transitions like superconductivity."

With Titan, Maier's team possessed the computing power necessary to solve the Hubbard model realistically and at low enough temperatures to observe pseudogap physics. The team gained access to Titan, a Cray XK7 with a peak performance of 27 petaflops (or 27 quadrillion calculations per second), through a 2015 Innovative and Novel Computational Impact on Theory and Experiment program allocation.

Designed by researchers at ORNL and ETH Zurich in Switzerland, DCA++ maximizes Titan's hybrid architecture by making use of the GPUs on each of Titan's 18,688 nodes. In past demonstrations on Titan, DCA++ has topped 15 petaflops. Furthermore, the DCA algorithm minimizes a common problem associated with calculating many-particle systems using the Monte Carlo method, the fermionic sign problem.

In physics, the quantum nature of electrons and other fermions is described by a wave function, which can switch from positive to negative--or vice versa--when two particles are interchanged. When the positive and negative values nearly cancel each other out, accurately calculating the many-particle states of electrons becomes tricky.

"The sign problem is affected by cluster size, temperature, and the strength of the interactions between the electrons," Maier said. "The problem increases exponentially, and there's no computer big enough to solve it. What you can do to get around this is measure physical observables using many, many processors. That's what Titan is good for."

DCA++ works by measuring notable physical characteristics of the model as it walks randomly through the space of electronic configurations. Running on Titan, the code allows for larger clusters of atoms at lower temperatures, providing a more complete snapshot of the pseudogap phase than previously achieved.

Transitioning to Temperature

Moving forward, Maier's team is focused on simulating more complex and realistic cuprate systems to study the transition temperature at which they become superconducting, a point that can vary greatly within the copper-oxide family of materials.

To take the next step, the team will need to use models with more degrees of freedom, or energy states, information that must be derived from first-principles calculations that take into account all the electrons and atoms in a system.

"Once we get that, we can ask why the transition temperature is higher in one material and lower in another," Maier said. "If you can answer that, you could do the same for any high-temperature superconductor or any material you want to simulate."

####

About Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Oak Ridge National Laboratory is supported by the US Department of Energy's Office of Science. The single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, the Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Jonathan Hines

865-574-6944

Copyright © Oak Ridge National Laboratory

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Superconductivity

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

![]() Lattice-driven charge density wave fluctuations far above the transition temperature in Kagome superconductor April 25th, 2025

Lattice-driven charge density wave fluctuations far above the transition temperature in Kagome superconductor April 25th, 2025

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||