Home > Press > Stanford researchers stretch a thin crystal to get better solar cells

|

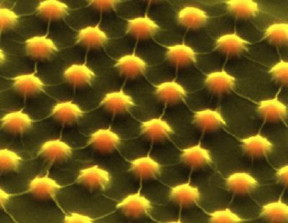

| This colorized image shows an ultra thin layer of semiconductor material stretched over the peaks and valleys of part of a device the size of a pinkie nail. Just three atoms thick, this semiconductor layer is stretched in ways enhance its electronic potential to catch solar energy. The image is enlarged 100,000 times. CREDIT: Hong Li, Stanford Engineering |

Abstract:

Nature loves crystals. Salt, snowflakes and quartz are three examples of crystals - materials characterized by the lattice-like arrangement of their atoms and molecules.

Stanford researchers stretch a thin crystal to get better solar cells

Stanford, CA | Posted on June 25th, 2015Industry loves crystals, too. Electronics are based on a special family of crystals known as semiconductors, most famously silicon.

To make semiconductors useful, engineers must tweak their crystalline lattice in subtle ways to start and stop the flow of electrons.

Semiconductor engineers must know precisely how much energy it takes to move electrons in a crystal lattice. This energy measure is the band gap.

Semiconductor materials like silicon, gallium arsenide and germanium each have a band gap unique to their crystalline lattice. This energy measure helps determine which material is best for which electronic task.

Now an interdisciplinary team at Stanford has made a semiconductor crystal with a variable band gap. Among other potential uses, this variable semiconductor could lead to solar cells that absorb more energy from the sun by being sensitive to a broader spectrum of light.

The material itself is not new. Molybdenum disulfide, or MoS2, is a rocky crystal, like quartz, that is refined for use as a catalyst and a lubricant.

But in Nature Communications, Stanford mechanical engineer Xiaolin Zheng and physicist Hari Manoharan proved that MoS2 has some useful and unique electronic properties that derive from how this crystal forms its lattice.

Molybdenum disulfide is what scientists call a monolayer: A molybdenum atom links to two sulfurs in a triangular lattice that repeats sideways like a sheet of paper. The rock found in nature consists of many such monolayers stacked like a ream of paper. Each MoS2 monolayer has semiconductor potential.

"From a mechanical engineering standpoint, monolayer MoS2 is fascinating because its lattice can be greatly stretched without breaking," Zheng said.

By stretching the lattice, the Stanford researchers were able to shift the atoms in the monolayer. Those shifts changed the energy required to move electrons. Stretching the monolayer made MoS2 something new to science and potentially useful in electronics: an artificial crystal with a variable band gap.

"With a single, atomically thin semiconductor material we can get a wide range of band gaps," Manoharan said. "We think this will have broad ramifications in sensing, solar power and other electronics."

Scientists have been fascinated with monolayers since the Nobel Prize-winning discovery of graphene, a lattice made from a single layer of carbon atoms laid flat like a sheet of paper.

In 2012, nuclear and materials scientists at MIT devised a theory that involved the semiconductor potential of monolayer MoS2.

With any semiconductor, engineers must tweak its lattice in some way to switch electron flows on and off. With silicon, the tweak involves introducing slight chemical impurities into the lattice.

In their simulation, the MIT researchers tweaked MoS2 by stretching its lattice. Using virtual pins, they poked a monolayer to create nanoscopic funnels, stretching the lattice and, theoretically, altering MoS2's band gap.

Band gap measures how much energy it takes to move an electron. The simulation suggested the funnel would strain the lattice the most at the point of the pin, creating a variety of band gaps from the bottom to the top of the monolayer.

The MIT researchers theorized that the funnel would be a great solar energy collector, capturing more sunlight across a wide swath of energy frequencies.

When Stanford postdoctoral scholar Hong Li joined the mechanical engineering department in 2013, he brought this idea to Zheng. She led the Stanford team that ended up proving all of this by literally standing the MIT theory on its head.

Instead of poking down with imaginary pins, the Stanford team stretched the MoS2 lattice by thrusting up from below. They did this - for real rather than in simulation - by creating an artificial landscape of hills and valleys underneath the monolayer.

They created this artificial landscape on a silicon chip, a material they chose not for its electronic properties, but because engineers know how to sculpt it in exquisite detail. They etched hills and valleys onto the silicon. Then they bathed their nanoscape with an industrial fluid and laid a monolayer of MoS2 on top.

Evaporation did the rest, pulling the semiconductor lattice down into the valleys and stretching it over the hills.

Alex Contryman, a PhD student in applied physics in Manoharan's lab, used scanning tunneling microscopy to determine the positions of the atoms in this artificial crystal. He also measured the variable band gap that resulted from straining the lattice this way.

The MIT theorists and specialists from Rice University and Texas A&M University contributed to the Nature Communications paper.

Team members believe this experiment sets the stage for further innovation on artificial crystals.

"One of the most exciting things about our process is that is scalable," Zheng said. "From an industrial standpoint, MoS2 is cheap to make."

Added Manoharan: "It will be interesting to see where the community takes this."

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Tom Abate

650-736-2245

Copyright © Stanford School of Engineering

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

Thin films

![]() Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Imaging

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Materials/Metamaterials/Magnetoresistance

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

![]() Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

![]() Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Tools

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Japan launches fully domestically produced quantum computer: Expo visitors to experience quantum computing firsthand August 8th, 2025

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Industrial

![]() Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

![]() Quantum interference in molecule-surface collisions February 28th, 2025

Quantum interference in molecule-surface collisions February 28th, 2025

![]() Boron nitride nanotube fibers get real: Rice lab creates first heat-tolerant, stable fibers from wet-spinning process June 24th, 2022

Boron nitride nanotube fibers get real: Rice lab creates first heat-tolerant, stable fibers from wet-spinning process June 24th, 2022

Solar/Photovoltaic

![]() Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

![]() KAIST researchers introduce new and improved, next-generation perovskite solar cell November 8th, 2024

KAIST researchers introduce new and improved, next-generation perovskite solar cell November 8th, 2024

![]() Groundbreaking precision in single-molecule optoelectronics August 16th, 2024

Groundbreaking precision in single-molecule optoelectronics August 16th, 2024

![]() Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode: photoelectrochemical water-splitting hydrogen production January 12th, 2024

Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode: photoelectrochemical water-splitting hydrogen production January 12th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||