Home > Press > New evidence for an exotic, predicted superconducting state

|

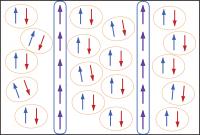

| A research team led by a Brown University physicist has produced new evidence for an exotic superconducting state, first predicted a half-century ago, that can arise when a superconductor is exposed to a strong magnetic field. Magnetism breaks electron Cooper pairs that enable superconductivity. The new research shows that those unpaired electrons congregate into discrete bands along the superconducting material. Those bands remain capable of conducting supercurrent.

Credit: Vesna Mitrovic / Brown University |

Abstract:

Superconductors and magnetic fields do not usually get along. But a research team led by a Brown University physicist has produced new evidence for an exotic superconducting state, first predicted a half-century ago, that can indeed arise when a superconductor is exposed to a strong magnetic field.

New evidence for an exotic, predicted superconducting state

Providence, RI | Posted on October 27th, 2014"It took 50 years to show that this phenomenon indeed happens," said Vesna Mitrovic, associate professor of physics at Brown University, who led the work. "We have identified the microscopic nature of this exotic quantum state of matter."

The research is published in Nature Physics.

Superconductivity — the ability to conduct electric current without resistance — depends on the formation of electron twosomes known as Cooper pairs (named for Leon Cooper, a Brown University physicist who shared the Nobel Prize for identifying the phenomenon). In a normal conductor, electrons rattle around in the structure of the material, which creates resistance. But Cooper pairs move in concert in a way that keeps them from rattling around, enabling them to travel without resistance.

Magnetic fields are the enemy of Cooper pairs. In order to form a pair, electrons must be opposites in a property that physicists refer to as spin. Normally, a superconducting material has a roughly equal number of electrons with each spin, so nearly all electrons have a dance partner. But strong magnetic fields can flip "spin-down" electrons to "spin-up", making the spin population in the material unequal.

"The question is what happens when we have more electrons with one spin than the other," Mitrovic said. "What happens with the ones that don't have pairs? Can we actually form superconducting states that way, and what would that state look like?"

In 1964, physicists predicted that superconductivity could indeed persist in certain kinds of materials amid a magnetic field. The prediction was that the unpaired electrons would gather together in discrete bands or stripes across the superconducting material. Those bands would conduct normally, while the rest of the material would be superconducting. This modulated superconductive state came to be known as the FFLO phase, named for theorists Peter Fulde, Richard Ferrell, Anatoly Larkin, and Yuri Ovchinniko, who predicted its existence.

To investigate the phenomenon, Mitrovic and her team used an organic superconductor with the catchy name κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu(NCS)2. The material consists of ultra-thin sheets stacked on top of each other and is exactly the kind of material predicted to exhibit the FFLO state.

After applying an intense magnetic field to the material, Mitrovic and her collaborators from the French National High Magnetic Field Laboratory in Grenoble probed its properties using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

What they found were regions across the material where unpaired, spin-up electrons had congregated. These "polarized" electrons behave, "like little particles constrained in a box," Mitrovic said, and they form what are known as Andreev bound states.

"What is remarkable about these bound states is that they enable transport of supercurrents through non-superconducting regions," Mitrovic said. "Thus, the current can travel without resistance throughout the entire material in this special superconducting state."

Experimentalists have been trying for years to provide solid evidence that the FFLO state exists, but to little avail. Mitrovic and her colleagues took some counterintuitive measures to arrive at their findings. Specifically, they probed their material at a much higher temperature than might be expected for quantum experiments.

"Normally to observe quantum states you want to be as cold as possible, to limit thermal motion," Mitrovic said. "But by raising the temperature we increased the energy window of our NMR probe to detect the states we were looking for. That was a breakthrough."

This new understanding of what happens when electron spin populations become unequal could have implications beyond superconductivity, according to Mitrovic.

It might help astrophysicists to understand pulsars — densely packed neutron stars believed to harbor both superconductivity and strong magnetic fields. It could also be relevant to the field of spintronics, devices that operate based on electron spin rather than charge, made of layered ferromagnetic-superconducting structures.

"This really goes beyond the problem of superconductivity," Mitrovic said. "It has implications for explaining many other things in the universe, such as behavior of dense quarks, particles that make up atomic nuclei."

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Kevin Stacey

401-863-3766

Copyright © Brown University

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Superconductivity

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Physics

![]() Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

![]() Magnetism in new exotic material opens the way for robust quantum computers June 4th, 2025

Magnetism in new exotic material opens the way for robust quantum computers June 4th, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Aerospace/Space

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() Onion-like nanoparticles found in aircraft exhaust May 14th, 2025

Onion-like nanoparticles found in aircraft exhaust May 14th, 2025

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||