Home > Press > Polymer-coated catalyst protects "artificial leaf"

|

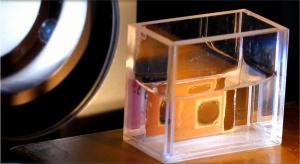

| This complex solar cell is coated with two different catalysts and works like an "artificial leaf", using sunlight to split water and yield hydrogen gas. |

Abstract:

Due to the fluctuating availability of solar energy, storage solutions are urgently needed. One option is to use the electrical energy generated inside solar cells to split water by means of electrolysis, in the process yielding hydrogen that can be used for a storable fuel. Researchers at the HZB Institute for Solar Fuels have modified so called superstrate solar cells with their highly efficient architecture in order to obtain hydrogen from water with the help of suitable catalysts. This type of cell works something like an "artificial leaf." But the solar cell rapidly corrodes when placed in the aqueous electrolyte solution. Now, Ph.D. student Diana Stellmach has found a way to prevent corrosion by embedding the catalysts in an electrically conducting polymer and then mounting them onto the solar cell's two contact surfaces, making her the first scientist in all of Europe to have come up with this solution. As a result, the cell's sensitive contacts are sealed to prevent corrosion with a stable yield of approx. 3.7 percent sunlight.

Polymer-coated catalyst protects "artificial leaf"

Berlin, Germany | Posted on June 17th, 2013Hydrogen stores chemical energy and is highly versatile in terms of its applicability potential. The gas can be converted into fuels like methane as well as methanol or it can generate electricity directly inside fuel cells. Hydrogen can be produced through the electrolytic splitting of water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen by using two electrodes that are coated with suitable catalysts and between which a minimum 1.23 volt tension is generated. The production of hydrogen only becomes interesting if solar energy can be used to produce it. Because that would solve two problems at once: On sunny days, excess electricity could yield hydrogen, which would be available for fuel or to generate electricity at a later point like at night or on days that are overcast.

New approach with complex thin film technologies

At the Helmholtz Centre Berlin for Materials and Energy (HZB) Institute for Solar Fuels, researchers are working on new approaches to realizing this goal. They are using photovoltaic structures made of multiple ultrathin layers of silicon that are custom-made by the Photovoltaic Competence Centre Berlin (PVcomB), another of the HZB's institutes. Since the cell consists of a single - albeit complex - "block," this is known as a monolithic approach. At the Institute for Solar Fuels, the cell's electrical contact surfaces are coated with special catalysts for splitting water. If this cell is placed in dilute sulphuric acid and irradiated with sun-like light, a tension is produced at the contacts that can be used to split water. During this process, it is the catalysts, which speed up the reactions at the contacts, that are critically important.

Protection against corrosion

The PVcomB photovoltaic cells' main advantage is their "superstrate architecture": Light enters through the transparent front contact, which is deposited on the carrier glass; there is no opacity due to catalysts being mounted onto the cells, because they are located on the cell's back side and are in contact with the water/acid mixture. This mixture is aggressive, that is to say, it is corrosive, so much so that Diana Stellmach had to first replace the usual zinc oxide silver back contact with a titanium coat approximately 400 nanometers thick. In a second step, she developed a solution to simultaneously protect the cell against corrosion with the mounting of the catalyst: She mixed nanoparticles of RuO2 with a conducting polymer (PEDOT:PSS) and applied this mixture to the cell's back side contact to act as a catalyst for the production of oxygen. Similarly, platinum nanoparticles, the sites of hydrogen production, were applied to the front contact.

Stable H2-Production

In all, the configuration achieved a degree of efficacy of 3.7 percent and was stable over a minimum 18 hours. "This way, Ms. Stellmach is the first ever scientist anywhere in Europe to have realized this kind of water-splitting solar cell structure," explains Prof. Dr. Sebastian Fiechter. And just maybe anywhere in the World, as photovoltaic membranes with different architectures have proved far less stable.

Yet the fact remains that catalysts like platinum and RuO2 are rather expensive and will ultimately have to give way to less costly types of materials. Diana Stellmach is already working on that as well; she is currently in the process of developing carbon nanorods that are coated with layers of molybdenum sulphide and which serve as catalysts for hydrogen production.

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Sebastian Fiechter

49-308-062-42927

Copyright © Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

![]() Watch the "artificial leaf" in action:

Watch the "artificial leaf" in action:

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Videos/Movies

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() New X-ray imaging technique to study the transient phases of quantum materials December 29th, 2022

New X-ray imaging technique to study the transient phases of quantum materials December 29th, 2022

![]() Solvent study solves solar cell durability puzzle: Rice-led project could make perovskite cells ready for prime time September 23rd, 2022

Solvent study solves solar cell durability puzzle: Rice-led project could make perovskite cells ready for prime time September 23rd, 2022

![]() Scientists prepare for the world’s smallest race: Nanocar Race II March 18th, 2022

Scientists prepare for the world’s smallest race: Nanocar Race II March 18th, 2022

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Solar/Photovoltaic

![]() Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

![]() KAIST researchers introduce new and improved, next-generation perovskite solar cell November 8th, 2024

KAIST researchers introduce new and improved, next-generation perovskite solar cell November 8th, 2024

![]() Groundbreaking precision in single-molecule optoelectronics August 16th, 2024

Groundbreaking precision in single-molecule optoelectronics August 16th, 2024

![]() Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode: photoelectrochemical water-splitting hydrogen production January 12th, 2024

Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode: photoelectrochemical water-splitting hydrogen production January 12th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||