Home > Press > Impurity Atoms Introduce Waves of Disorder in Exotic Electronic Material: Sophisticated electron-imaging technique reveals widespread "destruction," offering clues to how material works as a superconductor

|

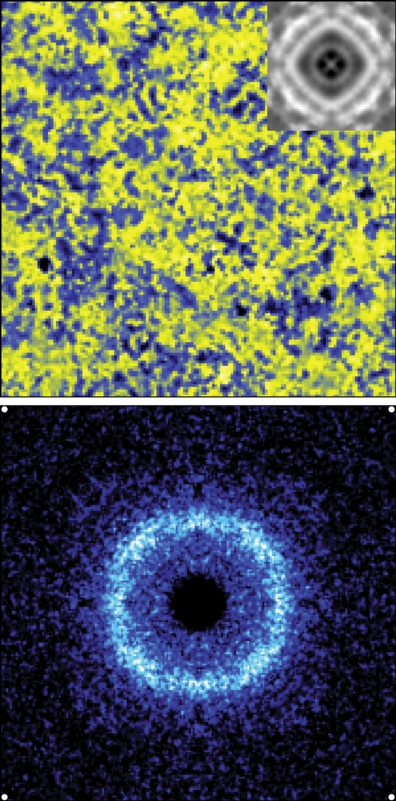

| Top: Visualization of nanoscale disruptions in electron interactions in a Kondo-hole doped heavy-fermion compound. The black-and-white inset shows directly how oscillations in electron behavior are centered on the Thorium impurities, "rippling" outward like disturbances caused by drops of water on a still pond. The rippling oscillations in electron energy are shown in more detail in the close-up view (bottom), where the bands of different shades of blue represent the distance between the ripples. |

Abstract:

It's a basic technique learned early, maybe even before kindergarten: Pulling things apart - from toy cars to complicated electronic materials - can reveal a lot about how they work. "That's one way physicists study the things that they love; they do it by destroying them," said Séamus Davis, a physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and the J.G. White Distinguished Professor of Physical Sciences at Cornell University.

Impurity Atoms Introduce Waves of Disorder in Exotic Electronic Material: Sophisticated electron-imaging technique reveals widespread "destruction," offering clues to how material works as a superconductor

Upton, NY | Posted on October 18th, 2011Davis and colleagues recently turned this destructive approach - and a sophisticated tool for "seeing" the effects - on a material they've been studying for its own intrinsic beauty, and for the clues it may offer about superconductivity, the ability of some materials to carry electric current with no resistance. The findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the week of October 17, 2011, reveal how substituting just a few atoms can cause widespread disruption of the delicate interactions that give the material its unique properties, including superconductivity.

The material, a compound of uranium, ruthenium, and silicon, is known as a "heavy-fermion" system. "It's a system where the electrons zooming through the material stop periodically to interact with electrons localized on the uranium atoms that make up the lattice, or framework of the crystal," Davis said. These stop-and-go magnetic interactions slow down the electrons, making them appear as if they've taken on extra mass, but also contribute to the material's superconductivity.

In 2010*, Davis and a group of collaborators visualized these heavy fermions for the first time using a technique developed by Davis, known as spectroscopic imaging scanning tunneling microscopy (SI-STM), which measures the wavelength of electrons of the material in relation to their energy.

The idea of the present study was to "destroy" the heavy fermion system by substituting thorium for some of the uranium atoms. Thorium, unlike uranium, is non-magnetic, so in theory, the electrons should be able to move freely around the thorium atoms, instead of stopping for the brief magnetic encounters they have at each uranium atom. These areas where the electrons should flow freely are known as "Kondo holes," named for the physicist who first described the scattering of conductive electrons due to magnetic impurities.

Free-flowing electrons might sound like a good thing if you want a material that can carry current with no resistance. But Kondo holes turn out to be quite destructive to superconductivity. By visualizing the behavior of electrons around Kondo holes for the first time, Davis' current research helps to explain why.

"There have been beautiful theories that predict the effects of Kondo holes, but no one knew how to look at the behavior of the electrons, until now," Davis said.

Working with thorium-doped samples made by physicist Graeme Luke at McMaster University in Ontario, Davis' team used SI-STM to visualize the electron behavior.

"First we identified the sites of the thorium atoms in the lattice, then we looked at the quantum mechanical wave functions of the electrons surrounding those sites," Davis said.

The SI-STM measurements bore out many of the theoretical predictions, including the idea proposed just last year by physicist Dirk Morr of the University of Illinois that the electron waves would oscillate wildly around the Kondo holes, like ocean waves hitting a lighthouse.

"Our measurements revealed waves of disturbance in the 'quantum glue' holding the heavy fermions together," Davis said.

So, by destroying the heavy fermions - which must pair up for the material to act as a superconductor - the Kondo holes disrupt the material's superconductivity.

Davis' visualization technique also reveals how just a few Kondo holes can cause such widespread destruction: "The waves of disturbance surrounding each thorium atom are like the ripples that emanate from raindrops suddenly hitting a still pond on a calm day," he said. "And like those ripples, the electronic disturbances travel out quite a distance, interacting with one another. So it takes a tiny number of these impurities to make a lot of disorder."

What the scientists learn by studying the exotic heavy fermion system may also pertain to the mechanism of other superconductors that can operate at warmer temperatures.

"The interactions in high-temperature superconductors are horribly complicated," Davis said. "But understanding the magnetic mechanism that leads to pairing in heavy fermion superconductors - and how it can so easily be disrupted - may offer clues to how similar magnetic interactions might contribute to superconductivity in other materials."

This research was supported by the DOE's Office of Science, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. Additional collaborators included Mohammad Hamidian and Ines Firmo of Brookhaven Lab and Cornell, and Andy Schmidt now at the University of California, Berkeley.

####

About Brookhaven National Laboratory

One of ten national laboratories overseen and primarily funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Brookhaven National Laboratory conducts research in the physical, biomedical, and environmental sciences, as well as in energy technologies and national security. Brookhaven Lab also builds and operates major scientific facilities available to university, industry and government researchers. Brookhaven is operated and managed for DOE's Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates, a limited-liability company founded by the Research Foundation of State University of New York on behalf of Stony Brook University, the largest academic user of Laboratory facilities, and Battelle, a nonprofit, applied science and technology organization. Visit Brookhaven Lab's electronic newsroom for links, news archives, graphics, and more at www.bnl.gov/newsroom , or follow Brookhaven Lab on Twitter, twitter.com/BrookhavenLab .

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Karen McNulty Walsh

(631) 344-8350

or

Peter Genzer

(631) 344-3174

Copyright © Brookhaven National Laboratory

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

![]() First Images of Heavy Electrons in Action:

First Images of Heavy Electrons in Action:

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Imaging

![]() ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

ICFO researchers overcome long-standing bottleneck in single photon detection with twisted 2D materials August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

![]() First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

First real-time observation of two-dimensional melting process: Researchers at Mainz University unveil new insights into magnetic vortex structures August 8th, 2025

Superconductivity

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

Laboratories

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Physics

![]() Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

Quantum computers simulate fundamental physics: shedding light on the building blocks of nature June 6th, 2025

![]() A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

A 1960s idea inspires NBI researchers to study hitherto inaccessible quantum states June 6th, 2025

![]() Magnetism in new exotic material opens the way for robust quantum computers June 4th, 2025

Magnetism in new exotic material opens the way for robust quantum computers June 4th, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||