Home > Press > Nanopores control the inner ear's ability to select sounds: Inner-ear membrane uses tiny pores to mechanically separate sounds, researchers find

|

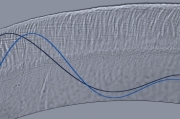

| This optical microscope image depicts wave motion in a cross-section of the tectorial membrane, part of the inner ear. This membrane is a microscale gel, smaller in width than a single human hair, and it plays a key role in stimulating sensory receptors of the inner ear. Waves traveling on this membrane control our ability to separate sounds of varying pitch and intensity. Image courtesy of MIT's Micromechanics Group |

Abstract:

Even in a crowded room full of background noise, the human ear is remarkably adept at tuning in to a single voice — a feat that has proved remarkably difficult for computers to match. A new analysis of the underlying mechanisms, conducted by researchers at MIT, has provided insights that could ultimately lead to better machine hearing, and perhaps to better hearing aids as well.

Nanopores control the inner ear's ability to select sounds: Inner-ear membrane uses tiny pores to mechanically separate sounds, researchers find

Cambridge, MA | Posted on March 18th, 2014Our ears' selectivity, it turns out, arises from evolution's precise tuning of a tiny membrane, inside the inner ear, called the tectorial membrane. The viscosity of this membrane — its firmness, or lack thereof — depends on the size and distribution of tiny pores, just a few tens of nanometers wide. This, in turn, provides mechanical filtering that helps to sort out specific sounds.

The new findings are reported in the Biophysical Journal by a team led by MIT graduate student Jonathan Sellon, and including research scientist Roozbeh Ghaffari, former graduate student Shirin Farrahi, and professor of electrical engineering Dennis Freeman. The team collaborated with biologist Guy Richardson of the University of Sussex.

Elusive understanding

In discriminating among competing sounds, the human ear is "extraordinary compared to conventional speech- and sound-recognition technologies," Freeman says. The exact reasons have remained elusive — but the importance of the tectorial membrane, located inside the cochlea, or inner ear, has become clear in recent years, largely through the work of Freeman and his colleagues. Now it seems that a flawed assumption contributed to the longstanding difficulty in understanding the importance of this membrane.

Much of our ability to differentiate among sounds is frequency-based, Freeman says — so researchers had "assumed that the better we could resolve frequency, the better we could hear." But this assumption turns out not always to be true.

In fact, Freeman and his co-authors previously found that tectorial membranes with a certain genetic defect are actually highly sensitive to variations in frequency — and the result is worse hearing, not better.

The MIT team found "a fundamental tradeoff between how well you can resolve different frequencies and how long it takes to do it," Freeman explains. That makes the finer frequency discrimination too slow to be useful in real-world sound selectivity.

Too fast for neurons

Previous work by Freeman and colleagues has shown that the tectorial membrane plays a fundamental role in sound discrimination by carrying waves that stimulate a particular kind of sensory receptor. This process is essential in deciphering competing sounds, but it takes place too quickly for neural processes to keep pace. Nature, over the course of evolution, appears to have produced a very effective electromechanical system, Freeman says, that can keep up with the speed of these sound waves.

The new work explains how the membrane's structure determines how well it filters sound. The team studied two genetic variants that cause nanopores within the tectorial membrane to be smaller or larger than normal. The pore size affects the viscosity of the membrane and its sensitivity to different frequencies.

The tectorial membrane is spongelike, riddled with tiny pores. By studying how its viscosity varies with pore size, the team was able to determine that the typical pore size observed in mice — about 40 nanometers across — represents an optimal size for combining frequency discrimination with overall sensitivity. Pores that are larger or smaller impair hearing.

"It really changes the way we think about this structure," Ghaffari says. The new findings show that fluid viscosity and pores are actually essential to its performance. Changing the sizes of tectorial membrane nanopores, via biochemical manipulation or other means, can provide unique ways to alter hearing sensitivity and frequency discrimination.

###

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health; the National Science Foundation; and the Wellcome Trust.

Written by David Chandler, MIT News Office

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Abby Abazorius

617-253-2709

Copyright © Massachusetts Institute of Technology

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

![]() Archive: Tuning in to a new hearing mechanism:

Archive: Tuning in to a new hearing mechanism:

![]() Archive: MIT finds new hearing mechanism:

Archive: MIT finds new hearing mechanism:

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

![]() "Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

"Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

![]() Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Institute for Nanoscience hosts annual proposal planning meeting May 16th, 2025

Nanomedicine

![]() New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

![]() "Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

"Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

Announcements

![]() Rice membrane extracts lithium from brines with greater speed, less waste October 3rd, 2025

Rice membrane extracts lithium from brines with greater speed, less waste October 3rd, 2025

![]() Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

Researchers develop molecular qubits that communicate at telecom frequencies October 3rd, 2025

![]() Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

Next-generation quantum communication October 3rd, 2025

![]() "Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

"Nanoreactor" cage uses visible light for catalytic and ultra-selective cross-cycloadditions October 3rd, 2025

Grants/Sponsored Research/Awards/Scholarships/Gifts/Contests/Honors/Records

![]() Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

![]() New discovery aims to improve the design of microelectronic devices September 13th, 2024

New discovery aims to improve the design of microelectronic devices September 13th, 2024

![]() Physicists unlock the secret of elusive quantum negative entanglement entropy using simple classical hardware August 16th, 2024

Physicists unlock the secret of elusive quantum negative entanglement entropy using simple classical hardware August 16th, 2024

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||