Home > Press > Achilles heel: Popular drug-carrying nanoparticles get trapped in bloodstream

|

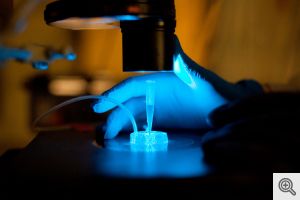

| Katawut Namdee, BME Ph.D. student, performs tests with different forms of drug carriers as part of the research done in ChE Professor Omolola Eniola Adefesco's lab in the GG Brown Building on North Campus Ann Arbor, MI on December 17, 2012. Image credit: Joseph Xu, Michigan Engineering Communications & Marketing |

Abstract:

Many medically minded researchers are in hot pursuit of designs that will allow drug-carrying nanoparticles to navigate tissues and the interiors of cells, but University of Michigan engineers have discovered that these particles have another hurdle to overcome: escaping the bloodstream.

Achilles heel: Popular drug-carrying nanoparticles get trapped in bloodstream

Ann Arbor, MI | Posted on February 5th, 2013Drug delivery systems promise precision targeting of diseased tissue, meaning that medicines could be more effective at lower doses and with fewer side effects. Such an approach could treat plaques in arteries, which can lead to heart attacks or strokes.

Drug carriers would identify inflamed vessel walls and deliver a drug that removes the deposits of calcium, cholesterol and other substances. Or, the carriers might seek out markers of cancer and kill off the small blood vessels in tumors, starving the malignant tissue of food and oxygen.

Nanoparticles, which have diameters under one micron, or one-thousandth of a millimeter, are thought to be the most promising drug carriers. Omolola Eniola-Adefeso, U-M professor of chemical engineering who studies nanoparticles in flowing blood, says the immune system can't get rid of them quickly.

"It's hard for a white blood cell to understand it has a nanoparticle next to it," she said.

Those same tiny dimensions allow them to slip through the cracks between cells and infiltrate cell membranes, where they can go to work administering medicine. But Eniola-Adefeso and her team found that these particles have an Achilles heel.

Blood vessels are the body's highways, and once nanoparticles get into the flow, they find it very difficult to reach the exits. In all vessels other than capillaries, the red cells in flowing blood tend to come together in the center.

"The red blood cells sweep those particles that are less than one micron in diameter and sandwich them," she said.

Trapped among the red cells, the nanoparticles can't reach the vessel wall to treat disease in the blood vessels or the tissue beyond.

With their recent work, including a study to be published recently in Langmuir, Eniola-Adefeso's team has shown that nanoparticle spheres face this problem in tiny arterioles and venules—one step up from capillaries—all the way up to centimeter-sized arteries.

They discovered this with the help of plastic channels lined with the same cells that make up the interiors of blood vessels. Human blood, with added nano- or microspheres, ran through the channels, and the team observed whether or not the spheres migrated to the channel walls and bound themselves to the lining. The researchers present the first visual evidence that few nanospheres make it to the vessel wall in blood flow.

"Prior to the work that we have done, people were operating under the assumption that particles will interact with the blood vessel at some point," Eniola-Adefeso said.

While a relatively small fraction of nanospheres filter out to the blood vessel walls, many more stay in the bloodstream and travel all over the body. Increasing the nanoparticle dose gives poor returns; after the team added five times more nanospheres to the blood samples, the number of spheres that bonded with the blood vessel lining only doubled.

"If localized drug delivery is an important goal, then nanospheres will fail," she said.

But it's not all bad news. The red blood cells tended to push microspheres with diameters of two microns or more toward the wall. Whether the blood flowed evenly, as it does in arterioles and venules, or in pulses, as occurs in arteries, the larger microspheres were able to reach the vessel wall and bind to it. When the team added more microspheres to the flow, they saw a proportional increase in microspheres on the vessel wall.

While microspheres are too large to serve as drug carriers into cell or tissue space on their own, the team suggested that microspheres could ferry nanospheres to the vessel wall, releasing them upon attachment. But the simpler approach may be nanoparticles of different shapes, which might escape the red blood cells on their own.

Eniola-Adefeso and her team are experimenting with rod-shaped nanoparticles.

"A sphere has no drift," she said, so nanospheres won't naturally move sideways out of the red cell flow. "When a rod is flowing, it drifts, and that drift moves it closer to the vessel wall."

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Kate McAlpine

734-763-4386

Copyright © University of Michigan

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

![]() The Cell Adhesion and Drug Delivery Lab:

The Cell Adhesion and Drug Delivery Lab:

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Nanomedicine

![]() New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

Cambridge chemists discover simple way to build bigger molecules – one carbon at a time June 6th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Safety-Nanoparticles/Risk management

![]() Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

![]() Onion-like nanoparticles found in aircraft exhaust May 14th, 2025

Onion-like nanoparticles found in aircraft exhaust May 14th, 2025

![]() Closing the gaps — MXene-coating filters can enhance performance and reusability February 28th, 2025

Closing the gaps — MXene-coating filters can enhance performance and reusability February 28th, 2025

Grants/Sponsored Research/Awards/Scholarships/Gifts/Contests/Honors/Records

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

Researchers tackle the memory bottleneck stalling quantum computing October 3rd, 2025

![]() New discovery aims to improve the design of microelectronic devices September 13th, 2024

New discovery aims to improve the design of microelectronic devices September 13th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||