Home > Press > Molecular depth profiling modeled with buckyballs and argon

|

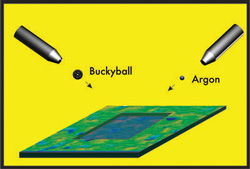

| The rectangular depression is the result of multiple bombardments of the surface with buckyballs and argon during a depth-profiling procedure. Image: Zbigniew Postawa, Jagiellonian University, Poland |

Abstract:

A team of scientists led by a Penn State University chemist has demonstrated the strengths and weaknesses of an alternative method of molecular depth profiling—a technique used to analyze the surface of ultra-thin materials such as human tissue, nanoparticles, and other substances. In the new study, the researchers used computer simulations and modeling to show the effectiveness and limitations of the alternative method, which is being used by a research group in Taiwan. The new computer-simulation findings may help future researchers to choose when to use the new method of analyzing how and where particular molecules are distributed throughout the surface layers of ultra-thin materials.

Molecular depth profiling modeled with buckyballs and argon

Philadelphia, PA | Posted on October 11th, 2011Team leader Barbara Garrison, the Shapiro Professor of Chemistry and the head of the Department of Chemistry at Penn State University, explained that bombarding a material with buckyballs—hollow molecules composed of 60 carbon atoms that are formed into a spherical shape resembling a soccer ball—is an effective means of molecular depth profiling. The name, "buckyball," is an homage to an early twentieth-century American engineer, Buckminster Fuller, whose design of a geodesic dome very closely resembles the soccer-ball-shaped 60-carbon molecule.

"Researchers figured out a few years ago that buckyballs could be used to profile molecular-scale depths very effectively," Garrison explained. "Buckyballs are much bigger and chunkier than the spacing between the molecules at the surface of the material being studied, so when the buckyballs hit the surface, they tend to break it up in a way that allows us to peer inside the solid and to actually see which molecules are arranged where. We can see, for example, that one layer is composed of one kind of molecule and the next layer is composed of another kind of molecule, similar to the way a meteor creates a crater that exposes sub-surface layers of rock."

Garrison and her colleagues decided to use computer modeling to test the effectiveness of an alternative approach that another research group had been using. The other group had used not only large, high-energy buckyballs to bombard a surface, but also another smaller, low-energy chemical element—argon—in the process. "In our computer simulations, we modeled the bombardment of surfaces first with high-energy buckyballs and then later, with low-energy argon atoms," Garrison said.

Garrison's group found that, with buckyball bombardment alone at grazing angles, the end result is a very rough surface with many troughs and ridges in one direction.

"In many instances, this approach works out well for depth profiling. However, in other instances, using buckyballs alone makes for a bumpy surface on which to perform molecular depth profiling because the molecules can be distributed unevenly throughout the peaks and valleys," Garrison explained. "In these instances, when low-energy argon bombardment is added to the process, the result is a much more even, smoother surface, which, in turn, makes for a better area on which to do analyses of molecular arrangement. In these cases, researchers can get a clearer picture of the many layers of molecules and exactly which molecules make up each layer."

However, Garrison's team also concluded that the argon must be low enough in energy in order to avoid further damage of the molecules that are being profiled.

"According to our simulations, the bottom line is that the buckyball conditions that the other research group used are not the best for depth profiling; thus, co-bombardment with low-energy argon assisted the process," Garrison said. "That is, the co-bombardment method works only in some very specific instances. We do not think low-energy argon will help in instances where the buckyballs are at sufficiently high energies." Garrison added that previous researchers had tried using smaller, simpler atomic projectiles at high, rather than low energies, but these projectiles tended to simply penetrate deeply into the surface, without giving scientists a clear view into the arrangement and identity of the molecules beneath.

Garrison said that molecular depth profiling is a crucial aspect of many chemical experiments and its applications are far-reaching. For example, molecular depth profiling is one way to get around the challenges of working with something so small and intricate as a biological cell. A cell is composed of thin layers of distinct materials, but it is difficult to slice into something so tiny to analyze the composition of those super-fine layers. In addition, molecular depth profiling can be used to analyze other kinds of human tissue, such as brain tissue—a process that could help researchers to understand neurological disease and injury. In the future, molecular depth profiling also could be used to study nanoparticles—extremely small objects with dimensions of between 1 and 10 nanometers, visible only with an electron microscope. Because nanoparticles already are being used experimentally as drug-delivery systems, a detailed analysis of their properties using molecular depth profiling could help researchers to test the effectiveness of the drug-delivery systems.

In addition to Garrison, other members of the research team include Zachary J. Schiffer, a high-school student at the State College Area High School near the Penn State University Park campus, Paul E. Kennedy of Penn State's Department of Chemistry, and Zbigniew Postawa of the Smoluchowski Institute of Physics at Jagiellonian University in Poland.

####

For more information, please click here

Copyright © Penn State University

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Nanotubes/Buckyballs/Fullerenes/Nanorods/Nanostrings/Nanosheets

![]() Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

![]() Enhancing power factor of p- and n-type single-walled carbon nanotubes April 25th, 2025

Enhancing power factor of p- and n-type single-walled carbon nanotubes April 25th, 2025

![]() Chainmail-like material could be the future of armor: First 2D mechanically interlocked polymer exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength January 17th, 2025

Chainmail-like material could be the future of armor: First 2D mechanically interlocked polymer exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength January 17th, 2025

![]() Innovative biomimetic superhydrophobic coating combines repair and buffering properties for superior anti-erosion December 13th, 2024

Innovative biomimetic superhydrophobic coating combines repair and buffering properties for superior anti-erosion December 13th, 2024

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Research partnerships

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

HKU physicists uncover hidden order in the quantum world through deconfined quantum critical points April 25th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||