Home > Press > Protein Shows How Plants Keep Their Mouths Shut

|

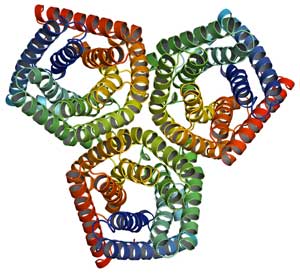

| The bacterial trimer (a compound of three macromolecules) studied by the researchers |

Abstract:

Findings could help researchers devise solutions to plant shutdown in face of rising carbon dioxide, ozone

Protein Shows How Plants Keep Their Mouths Shut

Upton, NY | Posted on October 28th, 2010Using intense beams of x-rays at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory, researchers have uncovered the atomic structure of a protein responsible for closing the "mouths," or stomata, of plants. These molecular photographs could help scientists understand how plants will respond to environmental changes facing our planet, such as drought and escalating levels of carbon dioxide and ozone. The study, led by researchers at Columbia University and the New York Structural Biology Center, is published in the October 28, 2010, issue of the journal Nature.

Plants "eat" and "breathe" through their stomata — tiny pores that pattern their leaves. When the sun is out, these small holes pull in carbon dioxide for energy generation through photosynthesis, and expel oxygen and water vapor. At night, to conserve moisture, the stomata are closed by a pair of kidney-shaped guard cells — the closest structure a plant has to muscle.

But darkness isn't the only signal that calls for guard cells to take action. Stomata also will seal up in response to high carbon dioxide levels, ozone, low humidity, and drought. In this study, researchers searched for details about the protein that starts the molecular chain reaction leading to stomata closure.

"Our work falls in the middle of an important discussion about how plants respond to environmental factors caused by global warming," said Columbia University scientist Wayne Hendrickson, who also is the Chief Life Scientist in Brookhaven's Photon Sciences Directorate. "Once we know this molecule intimately, we have a better chance of engineering solutions to help plants cope with pressures from environmental problems."

The protein in question is an anion channel, which moves negatively charged atoms (in this case, chloride) across the cell membrane to reduce the plant's water pressure. Low pressure causes the guard cells to go limp, and subsequently, the stomata to close.

Coincidentally, around the same time that this protein was discovered in plants, the Columbia-led team solved the structure of one of its close bacterial family members at Brookhaven's National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS).

At NSLS, researchers bombarded the bacterial protein with bright beams of x-rays and observed, via detectors and computers, how the light was diffracted from the atoms. They then analyzed these diffraction patterns to yield a 3-D snapshot of the protein's structure.

Although membrane proteins are notoriously difficult to characterize, the scientists ended up with a "spectacular" result, Hendrickson said. But the researchers were even more excited to learn about their protein's plant relative, which, up to that point, had an elusive structure.

"As soon as we learned about this link, we set out to follow up on the previous work done in the field and make a hypothesis about how the thing actually works," Hendrickson said.

Using the bacterial protein as a model for the plant version, and doing experiments on the plant protein itself, the scientists discovered the anion channel's "on" switch. This channel is typically in a very strained conformation that prevents anions from passing through it. But when phosphate attaches to the channel, its structure shifts and opens, allowing anions to freely flow. As a result, the water pressure drops and the stomata close.

"If we didn't have such high-resolution data, we wouldn't be able to tell if this was a mistake or part of the real structure. We wouldn't have been able to do this without the synchrotron," said Hendrickson. He added that this type of research will be even further advanced at Brookhaven's National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II), a facility currently under construction that will produce x-ray beams 10,000 times brighter and with much higher resolution than those at NSLS.

This study was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Protein Structure Initiative within the National Institutes of Heath and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Data were collected from NSLS beamline X4A, which is funded by the New York Structural Biology Center. NSLS is supported by the DOE Office of Science.

####

About Brookhaven National Laboratory

One of ten national laboratories overseen and primarily funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Brookhaven National Laboratory conducts research in the physical, biomedical, and environmental sciences, as well as in energy technologies and national security. Brookhaven Lab also builds and operates major scientific facilities available to university, industry and government researchers. Brookhaven is operated and managed for DOE's Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates, a limited-liability company founded by the Research Foundation of State University of New York on behalf of Stony Brook University, the largest academic user of Laboratory facilities, and Battelle, a nonprofit, applied science and technology organization.

For more information, please click here

Copyright © Brookhaven National Laboratory

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Food/Agriculture/Supplements

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() SMART researchers pioneer first-of-its-kind nanosensor for real-time iron detection in plants February 28th, 2025

SMART researchers pioneer first-of-its-kind nanosensor for real-time iron detection in plants February 28th, 2025

![]() Silver nanoparticles: guaranteeing antimicrobial safe-tea November 17th, 2023

Silver nanoparticles: guaranteeing antimicrobial safe-tea November 17th, 2023

Environment

![]() Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

![]() Onion-like nanoparticles found in aircraft exhaust May 14th, 2025

Onion-like nanoparticles found in aircraft exhaust May 14th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||