Home > Press > Crystal Defect Shown to be Key to Making Hollow Nanotubes

|

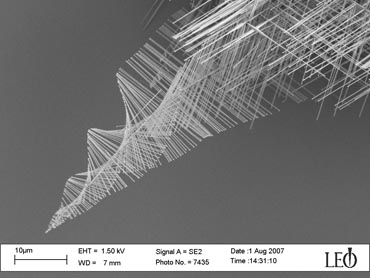

| Spiraling pine tree-like nanowires created by University of Wisconsin-Madison chemistry professor Song Jin and graduate student Matthew Bierman are evidence of an entirely different way of growing the tiny wires, one that could be harnessed to make better nanowires for applications such as high performance integrated circuits, LEDs and lasers, biosensors, and solar cells. The rapid elongation of the trunks is driven by a spiral defect within them called "screw dislocation," which causes them to twist as they grow and their branches to spiral. Photo by: courtesy Song Jin |

Abstract:

Scientists have no problem making a menagerie of nanometer-sized objects - wires, tubes, belts, and even tree-like structures. What they sometimes have been unable to do is explain precisely how those objects form in the vapor and liquid cauldrons in which they are made.

Crystal Defect Shown to be Key to Making Hollow Nanotubes

Madison, WI | Posted on April 24th, 2010Now a team led by University of Wisconsin-Madison chemist Song Jin, writing this week (April 23, 2010) in the journal Science, shows that a simple crystal defect known as a "screw dislocation" drives the growth of hollow zinc oxide nanotubes just a few millionths of a centimeter thick.

The finding is important because it provides new insight into the processes that guide the formation of the smallest manufactured structures, a significant challenge in nanoscience and nanotechnology. "We think that this work provides a general theoretical framework for controlling nanowire or nanotube growth without using metal catalysts that can be generally applicable to many materials," says Jin, a UW-Madison professor of chemistry.

Such materials and the Lilliputian structures scientists sculpt have already found broad applications in such things as electronics, solar power, battery and laser technology, and chemical and biological sensing. By further expanding the theory of how the tiny structures form, it should now be possible for scientists to develop new methods to mass produce nano-sized objects using a variety of different materials.

The method described by Jin and his colleagues depends on what scientists call a screw dislocation. Dislocations are fundamental to the growth and characteristics of all crystalline materials. As their name implies, these defects prompt the creation of spiral steps on an otherwise flawless crystal face. As atoms alight on the crystal surface, they form a structure strikingly similar in appearance to the spiral ramps of multistory parking structures. In earlier work, Jin and his research group showed that screw dislocations drive the growth of one-dimensional nanowire structures that looked like tiny pine trees. That, says Jin, was a critical clue to understanding the kinetics of spontaneous nanotube growth.

The key to understanding how to harness the defect to make nanostructures in a rational way, Jin explains, is knowing that as atoms collect on a surface of a dislocation spiral, strain associated with screw dislocations builds up in the tiny structures they create.

It turns out that "making the structure hollow and making it twist are two good ways of relieving such strain and stress," Jin explains. "In some cases, the large screw dislocation strain energy contained within the nanomaterial dictates that the material hollow out its center around the dislocation, thus resulting in the spontaneous formation of nanotubes."

The phenomenon described in the new Wisconsin work differs in significant ways from traditional mechanisms of making hollow nanostructures. Scientists now use templates to "mold" nanotubes or, alternatively, a diffusion process to convert one material into another with a hollow core. Carbon nanotubes are made, essentially, by rolling up a single honeycomb-patterned layer of carbon atoms.

The phenomena described by the Wisconsin team, Jin adds, should apply to materials beyond zinc oxide: "The understanding of the formation of nanotubes will certainly help us to understand related phenomena in other materials."

Refined, the new knowledge could ultimately be turned to the large scale, low cost production of nanomaterials for a wide range of applications. Most promising, says Jin, is the area of renewable energy where large amounts of such materials can be deployed to convert sunlight to electricity, and provide new raw materials for battery electrodes and thermoelectric devices.

The new work in Jin's lab was carried out by graduate students Stephen A. Morin and Matthew J. Bierman, with assistance from a former undergraduate student Jonathan Tong, all of UW-Madison. The work was funded primarily by National Science Foundation.

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Terry Devitt

(608) 262-8282

Copyright © University of Wisconsin-Madison

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

Chemistry

![]() Projecting light to dispense liquids: A new route to ultra-precise microdroplets January 30th, 2026

Projecting light to dispense liquids: A new route to ultra-precise microdroplets January 30th, 2026

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Nanotubes/Buckyballs/Fullerenes/Nanorods/Nanostrings/Nanosheets

![]() Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

Tiny nanosheets, big leap: A new sensor detects ethanol at ultra-low levels January 30th, 2026

![]() Enhancing power factor of p- and n-type single-walled carbon nanotubes April 25th, 2025

Enhancing power factor of p- and n-type single-walled carbon nanotubes April 25th, 2025

![]() Chainmail-like material could be the future of armor: First 2D mechanically interlocked polymer exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength January 17th, 2025

Chainmail-like material could be the future of armor: First 2D mechanically interlocked polymer exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength January 17th, 2025

![]() Innovative biomimetic superhydrophobic coating combines repair and buffering properties for superior anti-erosion December 13th, 2024

Innovative biomimetic superhydrophobic coating combines repair and buffering properties for superior anti-erosion December 13th, 2024

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Energy

![]() Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges August 8th, 2025

![]() Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Simple algorithm paired with standard imaging tool could predict failure in lithium metal batteries August 8th, 2025

Solar/Photovoltaic

![]() Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

Spinel-type sulfide semiconductors to operate the next-generation LEDs and solar cells For solar-cell absorbers and green-LED source October 3rd, 2025

![]() KAIST researchers introduce new and improved, next-generation perovskite solar cell November 8th, 2024

KAIST researchers introduce new and improved, next-generation perovskite solar cell November 8th, 2024

![]() Groundbreaking precision in single-molecule optoelectronics August 16th, 2024

Groundbreaking precision in single-molecule optoelectronics August 16th, 2024

![]() Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode: photoelectrochemical water-splitting hydrogen production January 12th, 2024

Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode: photoelectrochemical water-splitting hydrogen production January 12th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||