Home > Nanotechnology Columns > Cristian Orfescu > NanoArt Pioneers - Interview with Hugh McGrory

|

Cris Orfescu Founder NanoArt21 |

Abstract:

"NanoArt does not really need a definition. What needs to be stressed about it is that it is examining an area that will define the 21st Century, an area that will grow exponentially and change the way we think about the world. The images created in science labs (taken at the nanoscale) are NanoArt if they are presented as art." - Hugh McGrory

August 7th, 2008

NanoArt Pioneers - Interview with Hugh McGrory

Hugh McGrory is an established filmmaker based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. He was cofounder of Make.ie, a leading film and design house. Hugh has won numerous awards at film festivals around the world for his films. He was Executive Producer for the UK Film Council/Northern Ireland Screen 'Digital Shorts' Scheme from 2005/6 and now works as a Filmmaker/Research Consultant with Banjax ( http://www.banjax.com ) creating the 'cineclectic' online video project which will feature High Definition interviews with experts/experimenters in the areas of sound, image and web. In 2007 Hugh was working on a film research project at the Yale University CINEMA microscopy lab in collaboration with Dr. Derek Toomre and Adobe Systems Incorporated. The outcome was the movie ‘The Happy Cell', interviews with post-doc scientists at Yale University School of Medicine cut to their microscopy images, by Hugh McGrory and Fran Apprich. 'The Happy Cell is the name given by the scientists to the one cell out of thousands that is chosen for imaging. It's like a microscopic beauty contest!' You can view this movie together with other videos on http://cineclectic.tumblr.com

|

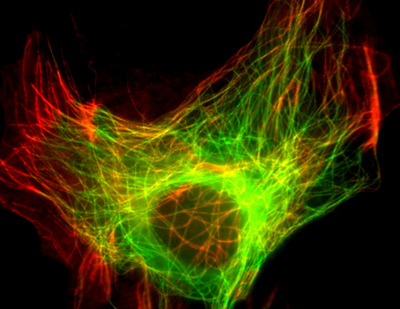

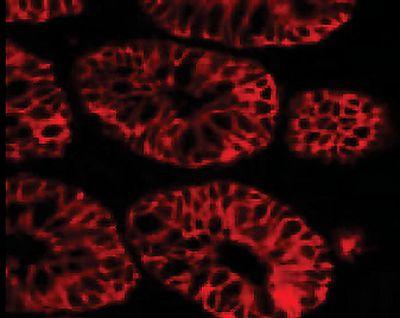

| MT_epi+TIR1, image by Dr Derek Toomre |

Hugh had the amability to answer a few of my questions:

Cris: Hugh, when did you start to be attracted by the nanoworld? What actually defines your attraction towards this small world?

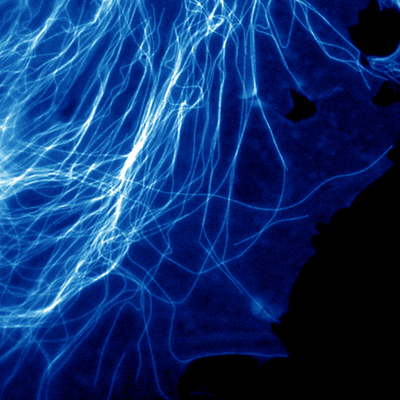

Hugh: Working as a filmmaker I have always been particularly interested in those images which technology can capture that are beyond the normal range of human perception. Living in Belfast I saw on television that a local company (Andor Technologies) were manufacturing microscopy cameras, so I went to visit them to see if they could provide images for a short film I was creating for the Irish Film Board. They put me in touch with Dr. Derek Toomre at the CINEMA microscopy lab in Yale University School of Medicine. I spent the summer there last year collecting and creating nanoimages. Dr. Toomre's images are incredible and his passion for his work is inspiring. We talked together about how there is huge interest from mainstream audiences in images from outerspace or underwater. Nanoimages are not as widely circulated but have the potential to ignite a similar reaction in the viewer. If you look at the kind of films people went to see in the early decades of cinema history you'll see that images beyond our everyday perception, microscopy for example, were extremely popular. So I suppose what I'm saying is that I'm interested in the nanoworld because I'm human and curious. I don't think there's anything special about this. I think that it is a 'normal' reaction.

|

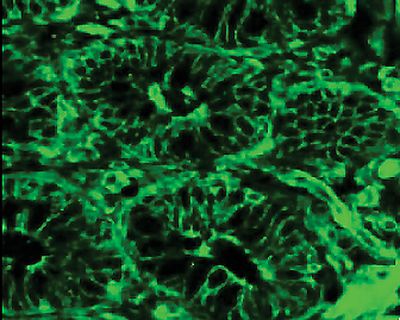

| Microtubules, image by Dr Derek Toomre |

Cris: How do scientists you collaborate with view your contribution to art-science-technology interactions?

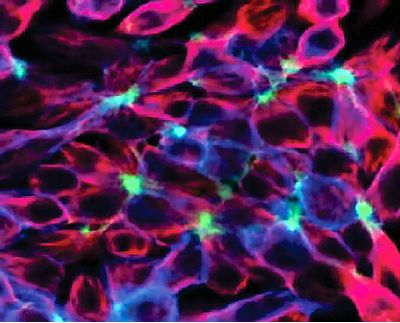

Hugh: The scientists I have worked with had a very open mind when it came to the question of the link between science, art and technology. They could see the science in what I did and I could see the art in their processes. The really interesting part is the exchange of ideas that happens when artists and scientists meet. Both are passionate about what they do. I can't really see the difference between the disciplines. I believe that these labels are artificial and can get in the way. They are outdated. At Yale, for instance, the scientists described the process of finding 'The Happy Cell' - the cell which is chosen specifically from hundreds or thousands to be used for imaging. This is a key decision since an 'unhappy' cell will not necessarily 'perform' under the microscope and can lead to wasted hours in the lab. It's similar to a nano beauty contest, the cell is defined as happy from how it looks, how it moves, what kind of shape it has, etc. The scientist uses an artistic eye for this. It is about feeling, gut, instinct, etc. It is good to understand that art, science and technology are not separate. Then we are able to learn from each other.

|

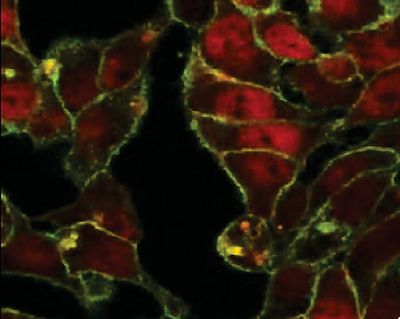

| Still image from ‘The Happy Cell' movie |

Cris: How would you define NanoArt?

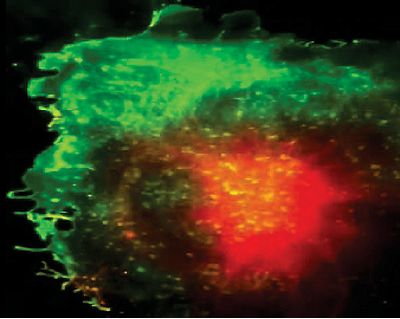

Hugh: Any 'art' is hard, if not impossible, to define. Defining 'nano' would be less difficult. You see, this is the art/science/tech question again in a way. Nano is a science word in essence and the addition of 'art' seems to be an attempt to rescue these stunning and deeply thought-provoking images from the pages of Nature or the archives of a laboratory. NanoArt does not really need a definition. What needs to be stressed about it is that it is examining an area that will define the 21st Century, an area that will grow exponentially and change the way we think about the world. The images created in science labs (taken at the nanoscale) are NanoArt if they are presented as art. Artists re-working these images can add extra dimensions but it is the images themselves that make us stand back and think and ask questions about what constitutes the world around us. What is all this 'stuff' made of? It's these questions and reactions that constitute the 'art' in my opinion.

|

| Still image from ‘The Happy Cell' movie |

Cris: What is your artistic process? Do you think your artistic process could be integrated in the NanoArt category?

Hugh: My artistic process involves working with technology to create images. I use the same basic tools as an imaging scientist. I use cameras and lenses for the creation of images and I use computers for the manipulation, editing and distribution of these images. That's what scientists do also. When the images I'm working with are taken at the nanoscale I suppose they can be described as NanoArt. I'm interested in combinations, in mixing things up, in cutting nanoimages together with the familiar 'real' world to make us question this 'reality'. The process is as interesting as the work, probably more interesting in fact since I get to meet people who are passionate and inspiring, people who are awake to the possibilities that emerging technologies can offer. The film industry sometimes feels like a History Department. Lots of people looking back and too few looking forward. I am most excited by those who view what they do as a continuing process of exploration.

|

| Still image from ‘The Happy Cell' movie |

Cris: I see some of your work is done in collaboration with Fran Apprich. Do you believe NanoArt is such a complex discipline that a lot of times it is necessary to put together a team to create a NanoArt work?

Hugh: Yes. NanoArt is like filmmaking. It requires tools, often expensive tools, which require a steep technical learning curve for their operation. A good filmmaker surrounds him or herself with a good crew. I don't need to be the camera operator if I can find someone who is as passionate about operating a camera as I am about directing a crew. Collaboration tends to make things better in my experience as long as there is a unified creative vision steering the project. When I worked with Fran, she specialized in sound and music and was very talented in this area but she also had other strengths such as picking the most beautiful images or finding the right questions to ask from her perspective. You learn early in filmmaking that it is a team effort. It is not necessarily about how complicated the process is, it's about wanting to do it to the best of your ability. Different people are good at different things. When you look at the cells and structures under the microscope it is fascinating to see how beautifully they work together. Things would be better if we all learned to do the same.

|

| Still image from ‘The Happy Cell' movie |

Cris: There is any message behind your nano-related work?

Hugh: That there is as much, if not more, beauty inside as out. That there is more to life than we imagine.

Recently, Hugh started the 'Cineclectic' Online Video Project and is interested in connecting with (and possibly filming interviews with) people worldwide who are helping to push the boundaries in the area of nanotech. Anyone interested can contact him on Linkedin or Twitter by following the links:

http://www.linkedin.com/in/hughmcgrory

http://twitter.com/mcgrory

|

| Still image from ‘The Happy Cell' movie |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||